How Halloween Took Root and Flourished in Spain

Friday, October 31, 2025

Spain, a nation celebrated for its deep-seated traditions like Día de Todos los Santos (All Saints' Day) on November 1st, has, in recent decades, enthusiastically embraced the global phenomenon of Halloween. What started as an "imported" holiday has blossomed into a vibrant, multi-layered celebration that skillfully blends modern fun with ancient Iberian and Celtic roots.

The relationship between Spain and the end-of-October observance is surprisingly complex, with both ancient roots and a relatively recent, rapid expansion:

-

Ancient Celtic Heritage (Samaín): The eerie roots of Spain's association with this time of year can be traced back thousands of years to the northwestern region of Galicia. Here, the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain ("end of summer") was celebrated. This traditional festival, known locally as Samaín or Noite dos Calacús (Night of the Pumpkins), marks the time when the veil between the living and the dead is thinnest.

-

Traditions: Even today, the modern revival of Samaín in Galicia involves carving pumpkins (or sometimes turnips), sharing ghost stories, lighting bonfires, and performing rituals like La Queimada (a flaming alcoholic punch with spells) to ward off evil spirits.

-

The Deep-Rooted Traditional Focus (Día de Todos los Santos): For centuries, the main focus in Spain has been the solemn and reflective Día de Todos los Santos on November 1st, followed by Día de los Fieles Difuntos (All Souls' Day) on November 2nd. These are national holidays dedicated to honouring the dead.

-

Customs: Families visit cemeteries to clean and elaborately decorate the graves of loved ones with fresh flowers, especially chrysanthemums, turning the cemeteries into vibrant places of remembrance and respect.

-

The American Cultural Tide: The rapid growth in the importance of Halloween (October 31st) began in the late 1980s and 1990s, largely driven by Anglo-Saxon cultural influence, particularly from the United States. Globalisation, horror movies, and television were key in introducing the now-familiar imagery of Jack-o'-lanterns, elaborate costumes, and "trick-or-treating" to Spanish society.

-

Growth: In large cities like Madrid and Barcelona, the celebration first gained a foothold in international schools, bars, and foreign communities. By the 2000s, the holiday was firmly established, especially among children and young people.

Modern Halloween in Spain is characterised by a fascinating mix, often celebrated over a three-day period that includes October 31st, November 1st, and November 2nd.

Modern Festivities on October 31st

The day, sometimes referred to as Día de las Brujas (Day of the Witches), is now a major occasion for contemporary celebration:

-

Costume Parties and Nightlife: Adults embrace the party spirit, with nightclubs, bars, and even themed events in amusement parks going all-out with elaborate decorations and costume parties.1 ostumes often lean toward the traditional spooky and macabre—ghosts, zombies, and vampires—though pop culture figures are increasingly common.

-

"Truco o Trato" (Trick-or-Treating): While not as universal or elaborate as in the US, "truco o trato" is now common in many urban neighbourhoods, schools, and community centres, especially for younger children.

-

Urban Spookiness: Cities like Barcelona and Málaga organise public parades, zombie marches, and haunted house experiences, creating a major spectacle.

The Culinary Bridge to All Saints' Day

The transition from the playful fright of Halloween to the reverence of All Saints' Day is often marked by traditional autumn foods, shared by families and friends:

-

La Castanyada (Catalonia): In Catalonia and parts of the north, the focus is on this traditional autumn festival, where people gather to eat castanyes (roasted chestnuts), boniatos (sweet potatoes), and panellets (small almond-based marzipan cakes).

-

Huesos de Santo: Across Spain, bakeries sell Huesos de Santo ("Saint's Bones"), small, marzipan-filled pastries, and Buñuelos de Viento (fried cream-filled fritters), tying the festivities to the religious holiday.

The Reverence of November 1st

Crucially, the fun of Halloween doesn't overshadow the respect for Día de Todos los Santos. Many Spaniards—particularly older generations—still prioritise this day of reflection, which offers a poignant contrast to the revelry of the previous night. It remains a significant family occasion centred on memorial, cemetery visits, and sharing special meals.

Halloween in Spain today is a perfect example of cultural syncretism. It successfully maintains ancient, local rituals in regions like Galicia, while simultaneously integrating the fun, commercialised appeal of the Anglo-Saxon holiday into its modern urban life, all while respecting the solemn, family-focused tradition of All Saints' Day. It has grown from a novelty to an established, highly anticipated event.

2

Like

Published at 9:20 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 9:20 PM Comments (0)

Home to the First Europeans - Burgos

Friday, October 24, 2025

The province of Burgos, with its present borders, dates back to the mid-19th century, and its capital, the City of Burgos, to the year 884 when it was founded by Count Diego Rodríguez Porcelos due to the population migrating down from the mountains in the north to the plains of the northern Meseta (central plateau). But the history of this area, and especially its pre-history, extends much further back…

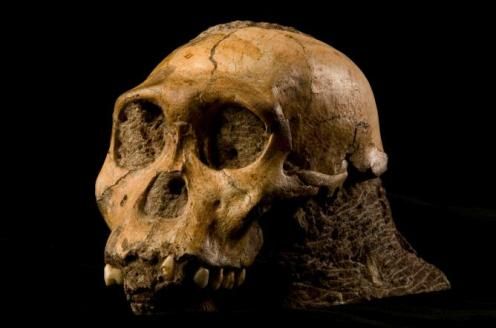

Human activity has left a deep and indelible mark on the province of Burgos. The most outstanding page from the past of Burgos must be sought in the hominid sites of Sierra de Atapuerca, where remains from over one million years ago have appeared of what has been considered as the first European. The excavations at Sierra de Atapuerca have permitted the modern world to rewrite the history of Europe and to know how we have evolved for millions of years. So far, they have found five different species: Homo Sp. (still to be determined, 1,200,000 years), Homo Ancestors (850,000 years), Homo Heidelbergensis (500,000 years), Homo Neanderthalenis (50,000 years,) and, of course, Homo Sapiens (us). The sanctuaries of cave paintings of Ojo Guareña; the dolmen group of Las Loras; the copious forts and necropolis of the Iron Age; the Roman town of Clunia and a considerable series of high-mediaeval necropolis and hermitages in La Demanda and Las Merindades are also of great importance to the province.

.jpeg)

Burgos is a territory where the historical origins of Castile were gestated and where the Castilian language was born, it is a province sown with incomparable and extremely beautiful samples of the cultural and artistic heritage. Its varied regions and towns are studded with churches, hermitages, monasteries, palaces, towers and castles from all times and styles. All of these remains are the unmistakable testimony of a dense and almost incomparable history. Few territories can boast such variety, quantity and quality of monuments.

The landscape of the province of Burgos radically breaks with the cliché that identifies Castile with an enormous and arid plateau. Mountains and plains form a relief where the strong contrast of its elements stand out. An enormous mosaic of ecosystems and natural landscapes, the ideal place to forget about the stress of busy town life and escape from the southern sweltering heat in summer and let yourself be carried away by the murmur of the water and wind.

The Province of Burgos is the centrepiece of the path traced by the Road to Santiago on the Iberian Peninsula. The strategic geographic placement of the Province of Burgos made it a necessary zone of transit for the millions of European pilgrims who made their way towards the Tomb of Santiago the Apostle from their home countries.

Over the course of the nearly 114 kilometres that cross its territory can be found an impressive collection of cultural landmarks. Its principal points of interest include Redecilla del Camino, Belorado, Villafranca Montes de Oca, San Juan de Ortega, the city of Burgos, San Antón and Castrogeriz.

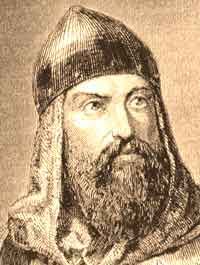

Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as “El Cid” Campeador, is Burgos' most universal figure. When examining the life of El Cid, a distinction must be drawn between two figures: the historic figure, about which there is a fair amount of information, and the literary figure created by the Poema de Mío Cid and by the Romancero. The historic El Cid was born around 1048. According to tradition, he was born in the nearby town of Vivar del Cid, though there is no reliable testimony. In his youth, he developed a friendship with the future king Sancho II, of whom he was a faithful vassal from 1065 to 1072. Upon the king's death, he immediately entered the service of Alfonso VI, and carried out different missions under the orders of the monarch. His good relationship with the king ended in 1081 when he attacked the Muslim lands of Toledo with his private army and without the consent of the King. The incident sent him into exile, which forced him to live off his military skills in foreign lands, first under the Muslim king of the taifa of Zaragoza, and following his reconciliation with Alfonso VI in 1087 and after several months of direct service to his king in Castile, in Levante where he spent the last twelve years of his life, first as the delegate of the Castilian king, and after being taken prisoner in 1088, in a second exile, as an independent warrior and prince of the Muslim kingdom of Valencia, in whose capital he died in 1099. A memorial statue of El Cid can be found in the centre of The City of Burgos.

One of the City of Burgos’ most important monuments is the Cathedral of Santa Maria. Built on the location of the original Romanesque cathedral, the first stone was laid in 1221 by King Ferdinand III and Bishop Don Mauricio. The main façade has the Royal Gate, also known as the Gate of Pardon, which was refurbished in the 18th century, and a large rose window and gallery with 8 statues of the monarchs of Castile beneath the statue of the Virgin Mary and the inscription “Pulcra es et Decora”. On both sides are the 84-metre towers crowned with slender spires from the 15th century, by Juan de Colonia. The tympanum of the Sarmental Gate, from the 13th century, shows Christ the healer with the four evangelists and, on a ledge below, the twelve apostles, with monarchs and musicians.

The mullion shows Bishop Don Mauricio with prophets and apostles to the sides. Above it, a beautiful rose window. The Coronería Gate, also known as that of the Apostles, is Gothic and shows Christ the Judge between Our Lady and St. John and, to the sides, a complex and majestic apostolate. The Pellejería Gate was built in 1516 by Francisco de Colonia. Above the transept is the dome, which was built in the 16th century and involved work by the masters Felipe de Vigarny and Juan de Vallejo. The chapel of El Condestable was built at the upper end by Simón de Colonia in the 15th century. It boasts a magnificent decoration of coats of arms and slender spires that form, together with those of the transept and those of the towers, an inimitable forest of stone with a wealth of statues and filigree work.

But Burgos isn’t just about monuments; with so much history it is hardly surprising that it is also a centre for gastronomy. Several of the dishes and preparations of the Burgos cuisine have gone beyond the provincial limits and have become the stars of the national culinary art. Suckling lamb roasted in a wood oven, rice black pudding and the fresh cheese from Burgos are the most well-known.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

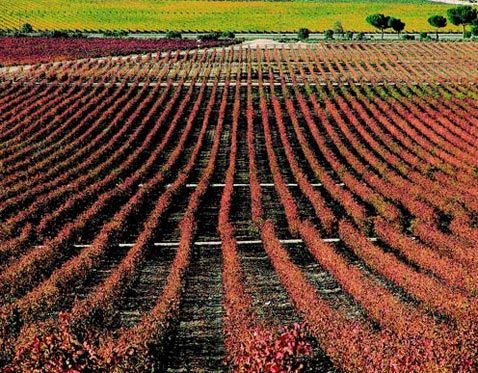

But it doesn’t stop there, it also happens to be one of the most respected wine regions in Spain as if falls at the banks of the River Duero and accounts for a large part of the denomination Ribera del Duero. The Ribera del Duero does not extend all the way along the banks of the River Duero (as its name suggests). The wines come from a specific area where nature is unique and the land is very special.

The lands included in the Ribera del Duero Designation are located on Spain`s northern plateau. Four of the provinces of the Autonomous Community of Castile & León come together in the Ribera del Duero: Burgos, Segovia, Soria and Valladolid.

The River Duero is the axis uniting more than 100 villages spread out over a wine growing belt which is some 115 Km long by 35 Km wide, of which 60 villages fall into the province of Burgos.

Spain’s most notable winery, Vega Sicilia is from this region and was established in 1864, but it wasn’t until the 1970’s that the region really took off internationally when the bodega Pesquera was founded and started to make red wines from Tempranillo in a more concentrated, full-bodied and fruit-driven style than most Rioja wines of the day, which were then virtually the only Spanish red wines found on export markets. Other prestigious bodegas are Emilio Moro, Protos, Arzuaga amongst others.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

Burgos is a land to enjoy with all the senses. The popular heritage treasured for centuries by the inhabitants of the province and of which its rich traditions and legends are a good example, its almost never-ending songs and its festivities and pilgrimages have left an incomparable trace, which confers upon the people of Burgos a unique and singular character and seasonal climate, a perfect synthesis between the European mildness and the Mediterranean luminosity.

Ver mapa más grande

BEST TIME TO VISIT:

Any time of year, but in winter it does get very cold and frequently snows, so for em the best time of year is Spring or Summer.

2

Like

Published at 10:50 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 10:50 PM Comments (0)

Back to 1925: Ochagavía, Spain, Preserves a Century-Old Way of Life

Saturday, October 11, 2025

Every year, as summer draws to a close, the quaint Spanish village of Ochagavía in Spain's northern region of Navarre undergoes a stunning transformation. The village sheds the 21st century—hiding traffic signs, ATMs, and modern storefronts—to faithfully recreate life as it was in 1925. This immersive experience, known as Orhipean (meaning "beneath Ori" in Basque), draws nearly 3,000 visitors annually, all eager to witness a bygone era brought vividly to life by the local residents.

For a full weekend, Ochagavía’s approximately 500 residents—some of whom return specifically for the event—don the outfits of the 1920s to perform the forgotten trades and customs of their ancestors.

The atmosphere is thick with authenticity, largely due to the dedication of the town's older generation, who instruct the young on the proper techniques. Visitors can watch:

- Washerwomen kneeling by the river, scrubbing sheets in the traditional way.

- Spinners using simple tools to process thread, a skill still held by the village's elders.

- Farmers shearing sheep with scissors and guiding livestock, including donkeys, through the cobblestone streets.

- A special, dramatic event: the "mata-txerri" or pig slaughter, where residents process the animal in the street, grinding meat and stuffing casings to make chorizo.

One of the most colourful attractions is the makeshift barber-dentist, a character who stands before a vintage price list. While a moustache trim costs 10 cents, a tooth extraction is priced based on bravery: free for those who endure the process without complaint, but one peseta for the "fussy" who require anaesthesia.

The commitment to detail extends beyond the public square. Homes and historical buildings are used to recreate private village life. The vestibule of a private house becomes the doctor’s office, while a Pyrenees mansion, Casa Koleto, houses a meticulously recreated old school. Here, separate schedules for boys and girls are observed, and a job advertisement for a female teacher lists strict, era-appropriate rules: "Do not marry," "do not dye your hair," and "wear at least two petticoats."

Religious customs are also revived, including the angélicas, a now-lost tradition where First Communion girls offered flowers to the Virgin Mary in May.

The Orhipean festival, which began over two decades ago, arose from a desire to turn the local celebration toward historical preservation. Organisers acknowledged that the event would not be possible without the complete involvement of the elderly, who share their living memories and family heirlooms, such as antique shoes and household items. The event’s newspaper, updated each year, offers historical context by featuring local happenings from the year 1925, detailing births, deaths, and even early morning weddings, serving as a powerful reminder of the deep roots and enduring spirit of this Navarrese community.

2

Like

Published at 11:47 AM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 11:47 AM Comments (0)

Unpacking Spain's 2025 Crime Data: The Cities with the Highest Rates

Friday, October 3, 2025

According to data from the first half of 2025, Spain maintains a relatively low position on international crime indices. Official figures released by the Ministry of the Interior show a slight year-on-year decrease in total recorded offences. However, a familiar pattern persists: the highest crime rates are concentrated in the country's largest and most visited metropolitan areas.

The data reveals that non-violent offences, such as pickpocketing and mobile phone snatches, form the majority of incidents, particularly in tourist hot spots.

City Crime Rates: Barcelona Leads the List

When crime is measured by the rate of offences per 100,000 residents, which allows for fair comparison between cities of different sizes, Barcelona ranks as the city with the highest rate in Spain for the first half of 2025.

Here are the cities with the highest recorded crime rates (offences per 100,000 residents) from January to June 2025:

|

City

|

Offences per 100,000 Residents

|

|

Barcelona

|

8,563

|

|

Madrid

|

7,980

|

|

Seville

|

6,450

|

|

Valencia

|

6,230

|

|

Málaga

|

5,875

|

|

Palma de Mallorca

|

5,540

|

|

Bilbao

|

5,300

|

|

Alicante

|

4,980

|

|

Zaragoza

|

4,730

|

|

Granada

|

4,500

|

Regional Trends

When looking at the sheer volume of conventional offences (not rates), Catalonia leads the autonomous communities with 207,567 incidents recorded. This is followed by Andalusia (160,038) and the Community of Madrid (159,705). These volume figures typically reflect population density, high tourist flows, and the presence of major transport hubs. The highest volumes of offences occur in the provinces of Barcelona and Madrid.

Safety Tips for Residents and Visitors

For both travellers and residents, safety concerns primarily revolve around opportunistic theft in crowded areas. Common locations for non-violent crimes include:

-

Barcelona: The tourist corridors of Ciutat Vella and around the Sagrada Família.

-

Madrid: The Sol–Gran Vía area.

-

Valencia: The historic city centre.

-

Málaga: The old town.

To minimise risk, authorities advise:

-

Keeping phones and wallets secured in zipped pockets or bags, especially on public transport and busy pavements.

-

Using a cross-body bag rather than a backpack.

-

Avoid leaving personal belongings unattended at beaches, nightlife spots, or festival sites.

The national emergency number in Spain is 112. Incidents should be reported by filing a denuncia with the Policía Nacional or Guardia Civil.

2

Like

Published at 5:55 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 5:55 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|