Ñ, the letter that almost disappeared...

Thursday, May 27, 2021

Ñ is the 15th letter in the Spanish alphabet and is used in more than 15,700 words. There’s no "Español" without ñ but even worse there would be no "cañas" either. The letter ñ was first included in the dictionary of RAE in 1803. But its origins stretch to the Middle Ages. The letter first appears in a text dating back to 1176. Ñ is the 15th letter in the Spanish alphabet and is used in more than 15,700 words. There’s no "Español" without ñ but even worse there would be no "cañas" either. The letter ñ was first included in the dictionary of RAE in 1803. But its origins stretch to the Middle Ages. The letter first appears in a text dating back to 1176.

Neither the sound or the letter ñ existed in Latin, but as the Latin language evolved and romantic languages such as Spanish, French and Italian began to appear, so too did the palatal nasal sound, which is articulated with the back of the tongue raised to the hard palate - the movement required to pronounce the ñ.

In the Middle Ages, monks were the scholars and the monasteries were the centres of knowledge. The letter ñ is thought to have originated at this moment in time due to the shortage of scrolls, which were very costly, and all efforts were made to maximise the efficiency of space on each scroll. As a result, it is believed that the monks were forced to abbreviate some double letters in order to fit more words in each line. According to this theory, the second repeated letter was represented as a tilde over the first. In other words, what we know as the ñ is in fact a double n, so instead of donna, we have doña.

However, there is another theory about the origin of this letter. According to this theory, the letter ñ emerged as a way to represent the new palatal nasal sounds that appeared in the ninth century. These words meant more work for the monks and so different adaptations began to emerge depending on the language. The letter ñ was used in Spanish and Gallego (España); the nh combination in Portuguese (Espanha); gn in French and Italian (Espagna); and ny in Catalan (Espanya).

These different forms continued to be used interchangeably until the 13th century when King Alfonso X of Castile and León ordered a spelling reform as part of his policy of linguistic unification. The monarch introduced the letter ñ as the preferred option to the previous combinations and in doing so set the first rules of the Spanish language. When the use of ñ became widespread across the Iberian peninsula, humanist Antonio de Nebrija included the letter in the first Spanish grammar book in 1492.

But it was not too long ago that the letter ñ was in danger of disappearing, at least from the written language. In the 1990s, the European Economic Community (EEC) proposed eliminating the ñ to make computer keyboards more uniform. It was not until October 2, 2007, that the ñ, as well as other tildes, could appear in email addresses and web domains.

The controversy ended on April 23, 1993, when the Spanish government approved a royal decree that maintained the mandatory inclusion of the letter ñ on keyboards.

But it is important to note that neither the letter ñ nor the sound is exclusively Spanish. In the Iberian peninsula, it is used in Gallego and Asturian, and also to a limited degree in the Basque language Euskera. In Latin America, many indigenous languages also include the letter, such as Mapuche in Chile and Argentina, Zapotec in Mexico and Quechua in Ecuador.

3

Like

Published at 10:07 PM Comments (2)

3

Like

Published at 10:07 PM Comments (2)

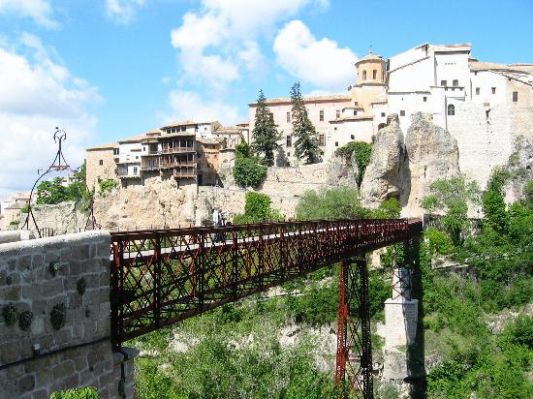

Discover Cuenca

Wednesday, May 19, 2021

.jpg)

The Old Town of Cuenca is an exceptional example of the medieval fortress town that has preserved its original townscape intact, along with many examples of religious and secular architecture from the 12th to 18th centuries. The walled town blends into and enhances the fine rural and natural landscape within which it is situated.

Cuenca is an ensemble, Islamic in origin, which reached its greatest splendour during the medieval and Renaissance centuries, when Cuenca had a leading place among the towns belonging to the Castilian crown. Cuenca is a 'fortress town' where the architecture conforms to the natural landscape, resulting in a cultural heritage of universal value. It may be considered a prototype of the 'landscape town'. The lack of space within the walls, along with the need to straddle the river valleys, has resulted an unusual development of the vernacular architecture, with exceptional groups on the cliffs overlooking the river Huécar and the Júcar.

When the Moors conquered Spain they took advantage of one of the best defensive sites on the lberian peninsula, to build a fortress-town from which to control the vast area of the Kura de Kunka, in the heart of the Caliphate of Córdoba. It developed between the castle and the Alcázar, adapting itself to the terrain.

Alfonso VIII of Castille captured the town in 1177 and Cuenca entered a new phase of its history as a "Royal town" and consequently Christian. The Christian town was built over the Moorish one and began to spread down from the crest of the hill. lt became a manufacturing town and one of the nuclei of the Castilian economy as well as an administrative centre.

During the 16th century Cuenca experienced a large increase in population, which tripled to some sixteen thousand by 1594. The intra-muros area was gradually taken over by religious institutions, the wealthier citizens moving to the lower parts of the town and the common people to new suburban areas. This was the period of Cuenca's flowering, with a large textile industry and flourishing trade.

The urban fabric stabilised itself at this time, not to change significantly until the present century: the fortified upper town is a closed and densely settled medieval urban space, the lower town open and ordered. The early 17th century saw the collapse of the textile industry and an economic crisis. Only the ecclesiastical element of the town survived relatively unscathed and continued to build: Cuenca became a monastic town and Baroque architecture began to appear in the townscape but the town underwent a period of deterioration: ancient buildings either collapsed or were demolished because they were unsafe. The historic fortified enclosure was virtually abandoned by its wealthier residents and became a largely working class and monastic area.

The rehabilitation plan of 1918 accomplished very little beyond the widening of some of the streets and restoration of some facades. The upper town is the archetype of the fortress-town, and the part that gives Cuenca its individual character. The Castillo quarter is a small suburb just outside the walls, with vernacular houses. From here the fortified town is reached by a bridge.

Some remains of the Moorish fortress still survive, among the large aristocratic houses, monasteries, and churches along San Pedro and Trabuco streets, from the medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods. The 12th-century cathedral, built on the site of the former Great Mosque and the first Gothic cathedral in Spain with its Plateresque chapels, is located on the Plaza Mayor, which is also the site of the Town Hall and the Petras convent. Its churches and monastic ensembles are notable artistic features of Cuenca.

Most were founded early in the town's history and underwent many transformations and additions over the centuries that followed. The private houses near the Episcopal Palace were built in the later medieval period on the spectacular steep bluffs overlooking the bend of the Huécar River. Most of them were rebuilt in the 16th century in their present narrow, high form, with two or three rooms on each of three or more floors. These houses are what have made Cuenca so popular as a tourist attraction, commonly known as the "Hanging Houses of Cuenca".

The importance of the upper town lies, however, not so much in its individual buildings, although many of these are of outstanding architectural and artistic quality, as in the townscape that they create when looked at as a group, on the fortified site dominating the river valleys. It is this which gives Cuenca its special character and quality.

Ver mapa más grande

2

Like

Published at 10:28 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 10:28 PM Comments (0)

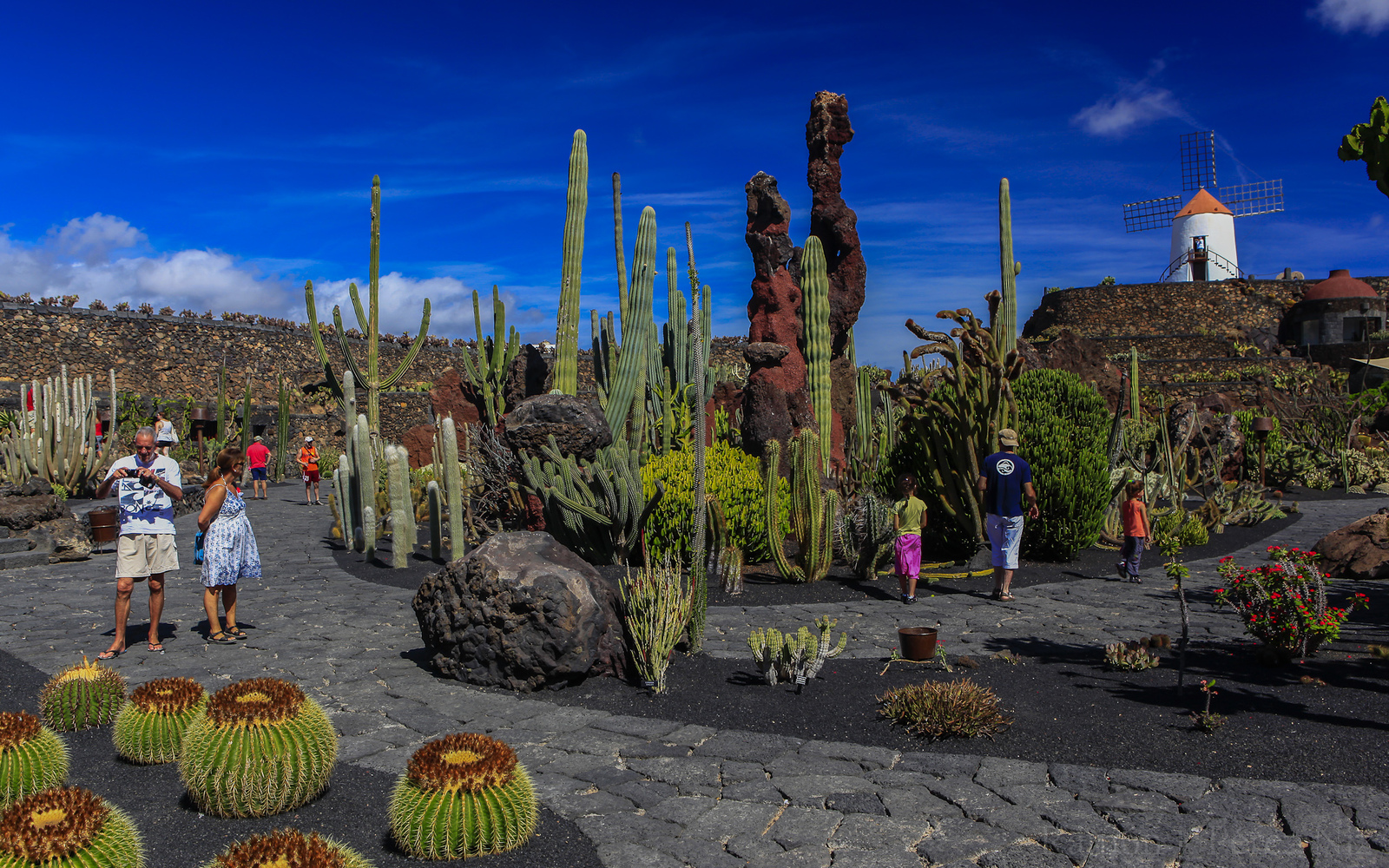

Guatiza Quarry

Thursday, May 13, 2021

The origins of the Jardín de Cactus date back to the 1970s, when César Manrique - then in full creative dialogue with the island's landscape - turned his attention to the old quarry at Guatiza.The former quarry was used for the extraction of volcanic ash and rock once used by prickly pear growers to conserve the ground’s nighttime moisture. The artist César Manrique saw in this location the chance to convert a disused area into an unusual and beautiful work of art.

The depression in the ground produced by the continual extraction of gravel had transformed the quarry into a dump. The artist encouraged the Cabildo de Lanzarote - a body with which he was working very closely - to acquire the land, wall in the complex and restore the traditional windmill that crowned the enclave. However, owing to various viscitudes, the original project to build a new Centre of Art, Culture and Tourism would have to wait until the 1980s. The Jardín de Cactus was finally opened in 1990 and became César Manrique's final spatial work.

The Jardín de Cactus is a magnificent example of an architectonic intervention integrated into the landscape. César Manrique created this audacious architectonic complex whilst maintaining the unshakeable pairing of art and nature that is so tangible in all of his spatial interventions.

It is located in Guatiza, municipality of Teguise, in the middle of an agricultural landscape characterised by extensive tunera plantations dedicated to the cultivation of cochineal.

The selection of this special landscape, as with so many of Manrique's works, dictated the aesthetic solutions adopted as well as the contents of the same, which have a sense of continuity and integration with the surrounding landscape. The large metal cactus at the entrance and the wrought iron gate stand out as unique referential and emblematic elements that presage the majestic and surprising character of the interior.

The entrance is formed by a labyrinthine set of robust, curved volumes, placed around a central structure in the form of a 'taro', the virtue of which is to occlude the view of the interior and therefore provoke a surprise effect on visitors.

On crossing the threshold, we are met with a view over the whole enclave. One of the main characteristics of this recreated amphitheatre is the walls, made up of terraces descending from the ground, in levels displaying different varieties of cactus.

A double staircase opens at our feet, inviting us to walk the sinuous stone paths and flights of stairs that connect the various landscaped areas in the interior.

At centre stage, we can see a series of monoliths made of compacted volcanic ash which have remained intact as evidence of the quarry's past extraction activities. The marked sculptural nature of these monoliths harmonises with the capricious, original shapes of the cacti. As an idyllic counterpoint to the aridity of the landscape, there are small ponds complete with water lilies and colourful fish.

In the Centre's five thousand square metres, there are over seven thousand two hundred examples of over one thousand one hundred different species, originating from places as far afield as Peru, Mexico, Chile, the United States, Kenya, Tanzania, Madagascar, Morocco and the Canary Islands. It is worth noting that the botanical collection at the Jardín de Cactus continues to increase, with periodic plantings of new species.

0

Like

Published at 9:50 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 9:50 PM Comments (0)

Defying Gravity

Monday, May 3, 2021

Unlike conventional stalactites, which are formed in a downwards direction in accordance with the law of gravity, eccentric stalactites grow randomly in any direction, like the branches of a tree. They are not very common and when there are two or more in one place they are quite spectacular to see. The Pozalagua Cave in Carranza, the westernmost town in Biscay, has an abundance of them. No other cavity in the world has so many.

It is a speleological feast, a marvellous pandemonium of eccentric stalactites woven together forming masses like roots and corals. It was discovered in a somewhat unusual way in 1957, not from careful prospecting, but from a charge of dynamite in a nearby dolomite quarry; this accidentally opened up this 125-metre long, 70-metre wide and 12-metre high vault. The guides explain to visitors that no air currents, roots or magnetic fields were involved in the formation of the eccentric stalactites. They crystallise like that.

Outside of the cave, the old dolomite quarry has been restored and is now the site of an amphitheatre where concerts are held in the summer. The limestone rock has been cut with diamond wire so perfectly that it seems the terraces have been sculpted from a block of marble.

In the same town, there is also the Karpin Abentura Wild Animal Shelter, where visitors can go to see a large number of illegally trafficked animal species, abandoned exotic pets and other species unable to return to the wild. They are all cared for in a privileged environment with a multitude of flora species from all the continents. Another great curiosity of the Enkarterri area is the Miguel de la Vía collection, in Galdames. It is made up of more than 70 antique and classic cars, which are displayed in the 13th century Loizaga Tower. The collection includes all models of Rolls-Royce up until the company was taken over by BMW in 1998.

If there is still time and you would like to see more of the area, in Balmaseda there is the Muza Bridge. It exudes the Middle Ages from all of its stones and even the tower where the 'bridge tax' was paid in the middle ages is still intact. You can also visit the Boinas La Encartada factory/museum. Balmaseda is also a good place to recharge your batteries. The typical dish here is 'putxera', a bean stew that was cooked in a pot by workers on the La Robla-Bilbao mining railway using the steam generated from the engine. The putxera has a monument and a festival, on 23 October, dedicated to it. No less traditional is the 'txakoli', which has been made in Balmaseda since the end of the 15th century.

3

Like

Published at 2:52 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 2:52 PM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|