Making friends, and enemies.

Friday, November 26, 2021

While Columbus was planting the symbolic flag of Castile and Aragon in the sand and giving his speech, the natives had come out of the forest and onto the beach to see what these strange men were doing. Totally naked, but wearing rings, bracelets, anklets and necklaces they surrounded the solemn group of Spaniards. Columbus’ crews watched them warily, but were not concerned; none of the natives were armed, and they were. However, the crew and visiting dignitaries noted that some of the baubles that the natives were wearing were made from gold. With the formalities over, Columbus ordered the distribution of brightly coloured caps and beads to the natives, which in his own words were “Of slight value, but in which they took great pleasure.”

One of two flags used by Colunbus to claim the islands for Isabel and Ferdinand. One of two flags used by Colunbus to claim the islands for Isabel and Ferdinand.

Columbus described the natives in his log. “They were very well built with very handsome bodies, and very good faces. Their hair was almost as coarse as horses' tails and short, and they wear it over the eyebrows, except a small quantity behind, which they wear long and never cut. Some paint themselves blackish, and they are of the colour of the inhabitants of the Canaries, neither black nor white, and some paint themselves white, some red, some whatever colour they find: and some paint their faces, some all the body, some only the eyes, and some only the nose. They do not carry arms nor know what they are, because I showed them swords and they took them by the edge and ignorantly cut themselves. They have no iron: their spears are sticks without iron, and some of them have a fish's tooth at the end and others have other things.”

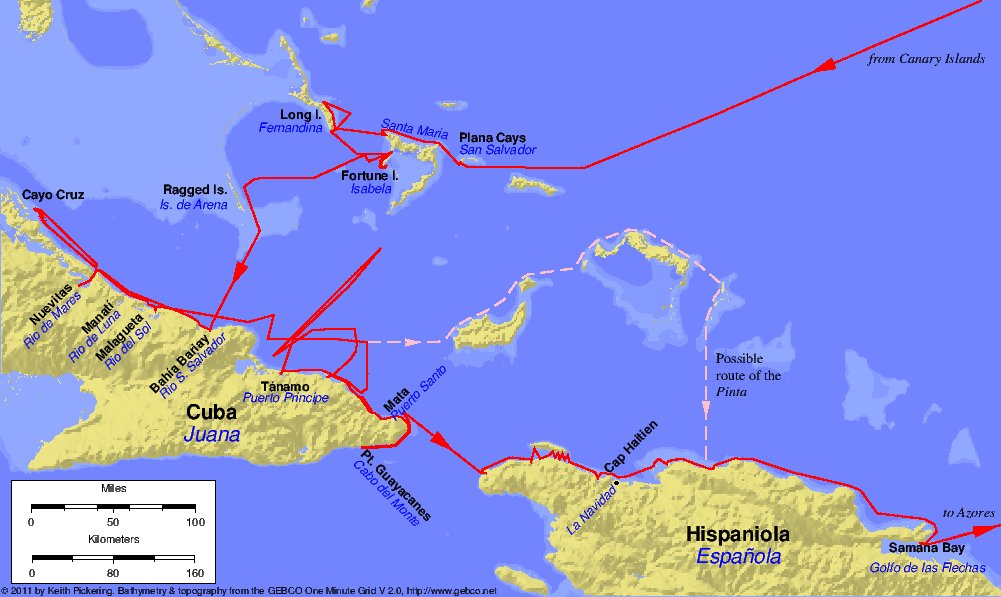

Using sign language and a few learned words, Columbus ascertained that the natives called the island Guanahan, which was probably one of the Plana Cays islands in the Bahamas. He was still of the opinion that he had landed on islands to the east of Cipango, (Portuguese for Japan) and he noted this in his log. Convinced that he must continue sailing westwards to find China, (The log showed later amendments replacing Japan with Cathay, or China.) he began questioning the natives about nearby islands. He especially wanted to know the source of the gold in their jewellery. With a number of native guides on board he took his small fleet further westwards and called at other islands giving each of them names in honour of Spain. (Santa Maria de la Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabela.) The three ships finally landed at Bariay Bay, Cuba on October 28. Columbus named the island Juana and began exploring the coastline.

Each time the three ships passed a settlement, the natives paddled their canoes out to greet the newcomers to invite them to see their villages. Columbus wrote that they were friendly and helpful and lived in a pyramidal tribal structure with village chiefs who acted as arbiter for disputes. By 5th November Columbus’ men had collected samples of spices which would fetch a good price in European markets. Columbus was pleased with the spices, but he had had never forgotten that it was his promise of gold that had persuaded Isabel and Ferdinand to support him, and he questioned the natives relentlessly about the source of their gold jewellery. He was told that the gold came from a nearby island called Babeque.

On the 6th, they were invited to a feast in a mountain village of 50 houses, which Columbus estimated had a population of 1000. As the Spaniards learned more of the language, they realised that the natives thought the Spanish were from heaven. They were shown around the village and invited into the houses, where they noted that the wooden furniture was often elaborately carved in the shape of animals, but with eyes and ears fashioned in gold.

It was here that the Spanish were invited to smoke tobacco for the first time, and they packed a sample the aromatic leaves in with the large amount of spices they had collected. They knew that the spices were expensive in Spain, and would be of interest to the traders. The tobacco leaves were an afterthought because they had no obvious value. (Of course, tobacco spread throughout Europe and Asia and gave pleasure to millions, but in hindsight, probably brought early death to millions.)

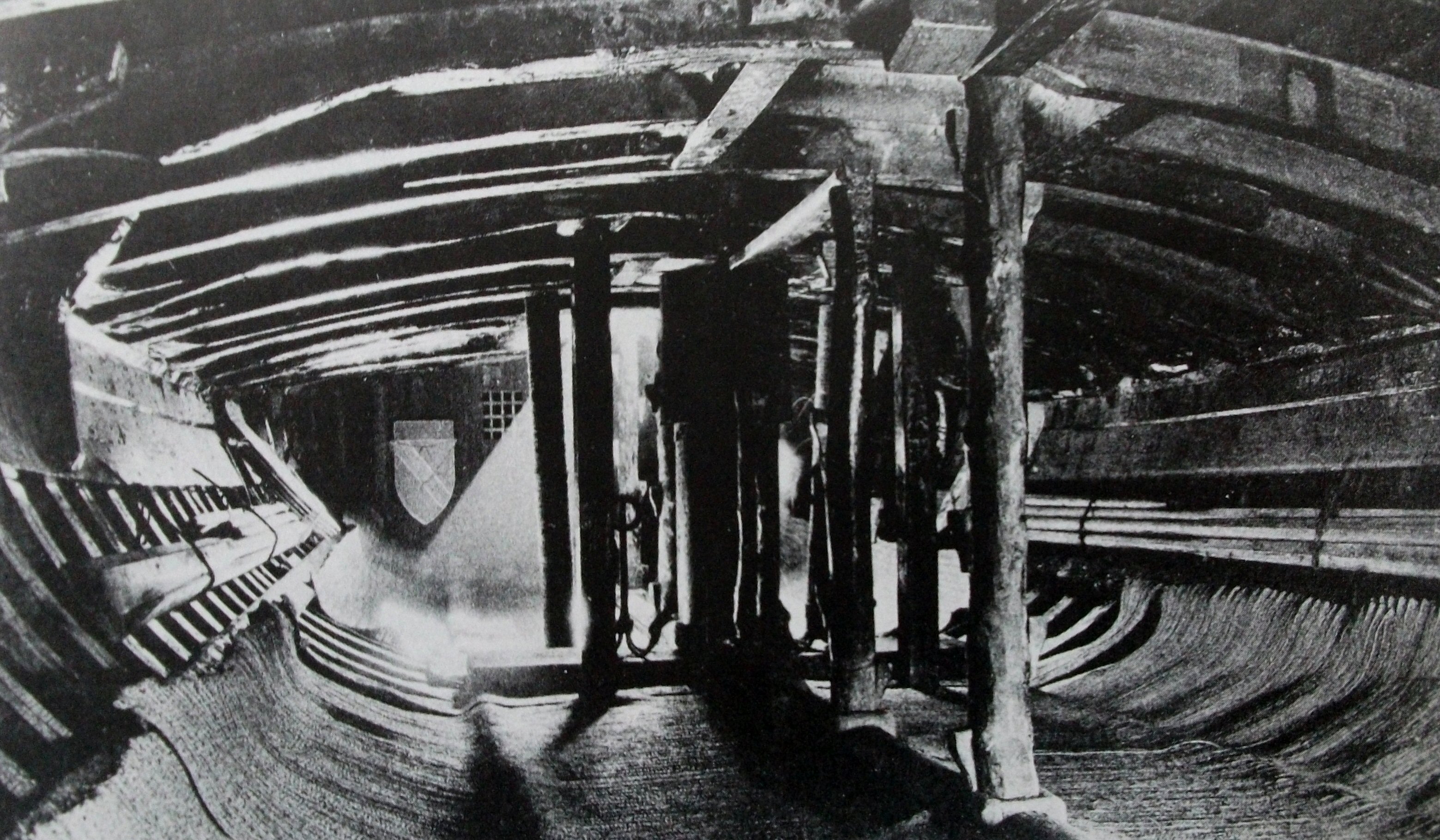

The Hold of the Santa Maria. Museo Maritim Barcelona.

What immediately caught the attention of the sailors were the hammocks that the natives slept in. For the natives, the hammocks were essential because they raised the sleeper off the ground where insects and poisonous snakes were a constant danger. For the sailors who slept in tiered bunks they were a revelation. To be rolled out of the top bunk in heavy weather often meant broken bones, but here was a bed that swung with the movement of the ship and left the occupant undisturbed. Even during relatively calm weather, anybody who has tried to sleep in a wooden bunk on a ship that rolls and pitches will testify that it is misery. Trading was brisk in hammocks, and when the three ships returned to Spain, many of the crew would spend their rest-time sleeping soundly in their hammocks. This astoundingly simple idea spread throughout every navy, and was probably the only thing from Columbus’ voyage that would benefit sailors everywhere who were about to face much longer voyages of trade and exploration.

Above: The gun deck of the Santa Maria where many of the sialors would have slept. Museo Maritim Barcelona.

By 1590, hammocks had been almost universally adopted for use in sailing ships; the Royal Navy formally adopted the sling hammock in 1597 when it ordered three hundred bolts of canvas for "hanging cabbons or beddes”. Aboard ship, hammocks were regularly employed for sailors sleeping on the gun decks of warships, where limited space prevented the installation of permanent bunks.

Columbus gave orders to encourage some of the natives to come on board his ships with the intention of using them as guides to help navigate amongst the islands, but with a longer term plan to take some of them back to Spain to show the king and queen. With natives on each ship, the little fleet sailed north-east along the coast of Cuba. Columbus was still convinced that he was off the Chinese mainland and was determined to present himself to the Great Kahn in Cathay. The wind was against the fleet and they made little headway before returning to a river that the admiral had called Rio de Mares. By now many of the natives were becoming wary of the Spaniards’ motives in keeping them aboard their ships. He sent parties ashore, but the natives of the villages had abandoned their villages and fled, and he ordered his men not to take anything and leave the villages untouched.

Finally, a canoe with six youths approached the Santa Maria and five of them came aboard. Columbus immediately ordered them to be restrained. He sent men out to search for natives, and they returned with seven captured women and three children. Later on that evening, the father of the children and husband of one of the women came to ask to be reunited with his family and Columbus kept them all together. In his log he writes that he was pleased that the natives had decided to stay and that he would present them to the king and queen, but it had become clear to the natives that they were prisoners not guests. Finally, Columbus decided that he had enough spices to tempt the European traders, and gave orders to prepare for the voyage to Babeque to find the source of the gold.

The captain of the Pinta, Martin Alonso Pinzón, had fallen out with Columbus on several occasions before and during the voyage, and now he had natives aboard who told him that they could take him to the island of Babeque and show him where the gold was mined. They must have told Pinzón much more than they told Columbus, because Pinzón secretly hatched his plan to go gold hunting alone.

On 21 November, as the fleet prepared to sail to Babeque, Pinzón had a blazing row with Columbus, and when the ships left the coast of Cuba, the Pinta, being the fastest ship in the fleet, pulled away into the lead. The log shows that the ships made several course changes in open water before the Santa Maria and Niña returned to the coast of Cuba whilst the Pinta went off alone. Columbus was furious, but adverse winds kept the remainder of his fleet at anchor off the coast of Cuba. The lure of fame and fortune was beginning to erode the discipline of the small fleet, and it was only going to get worse as the voyage continued.

Log extracts show the confused courses plotted just before the Pinta left the other two ships. Map: Keith Pickering.

After Martin Alonzo Pinzón pressed on with his own search for gold in the Pinta and leave the other ships behind, Columbus changed course to the south-east. The Santa Maria and Niña held this course through the night, but in the morning they discovered that they had made little progress. The wind and adverse currents had been against them. Columbus rightly guessed that Pinzón in the Pinta had also made little progress, so he ordered that the next night he would show a light so that Pinzón could return. Whether Pinzón never saw the beacon or chose to ignore it is not known, but the next morning with the wind against him, and with no sign of the Pinta, Columbus ordered his ships to turn back to the coast. When they landed, the Indians fled and would make no contact. His men found cultivated fields and a canoe made from a single tree that was easily capable of crossing between the islands, but not a single native was to be found.

With the wind against them, the two ships dropped anchor and sheltered in the mouth of a river. Everybody was impressed with the variety of trees and grasses, many of which they recognised as the same as in Spain, but on every foray inland, the natives eluded them. The natives that he had on board as guides were pleading to be allowed to be returned to their homes and families and they warned Columbus that the natives on this new coast were dangerous, and that he should not try to deal with them. But Columbus had not come this far to be deterred by unarmed savages. From what he had seen so far, they were the most docile and friendly of people, once you gained their trust. He had yet to see the natives carrying any kind of weapon that would be a threat to musket, sword and cannon.

2

Like

Published at 10:32 AM Comments (3)

2

Like

Published at 10:32 AM Comments (3)

A sea of lies

Friday, November 19, 2021

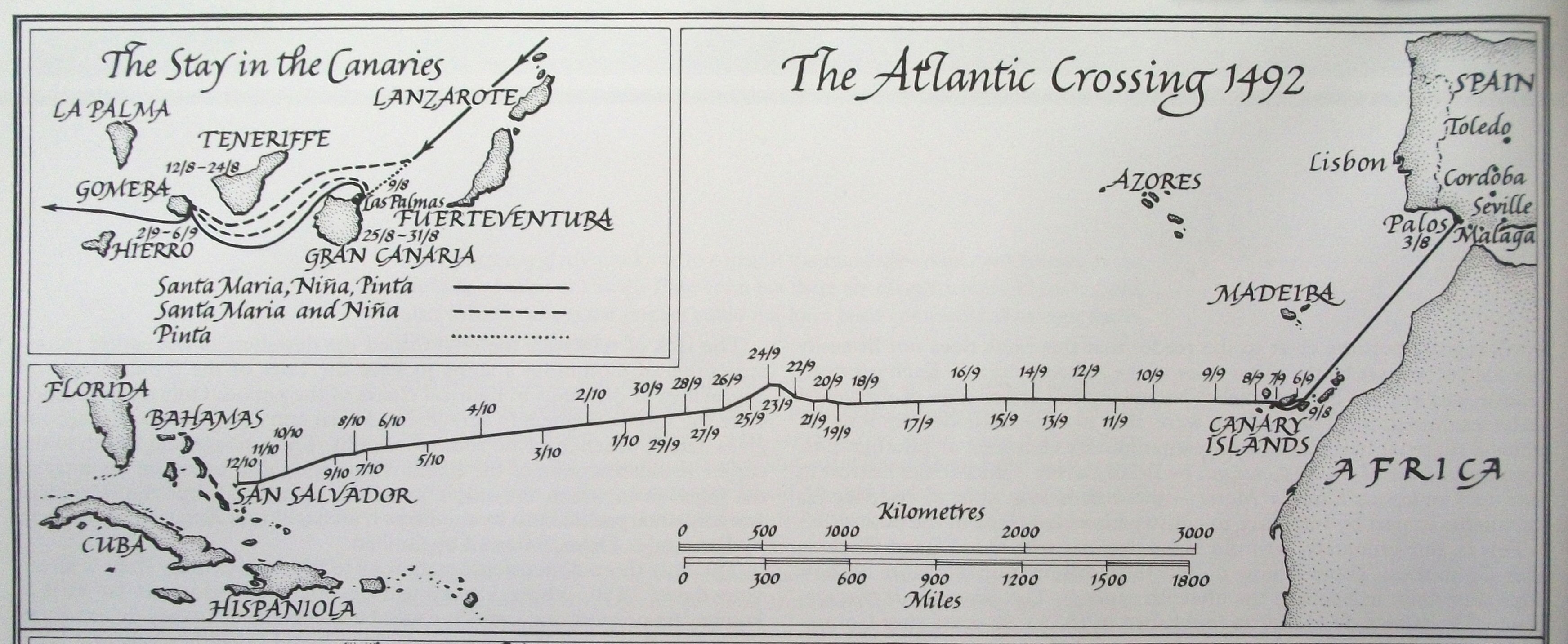

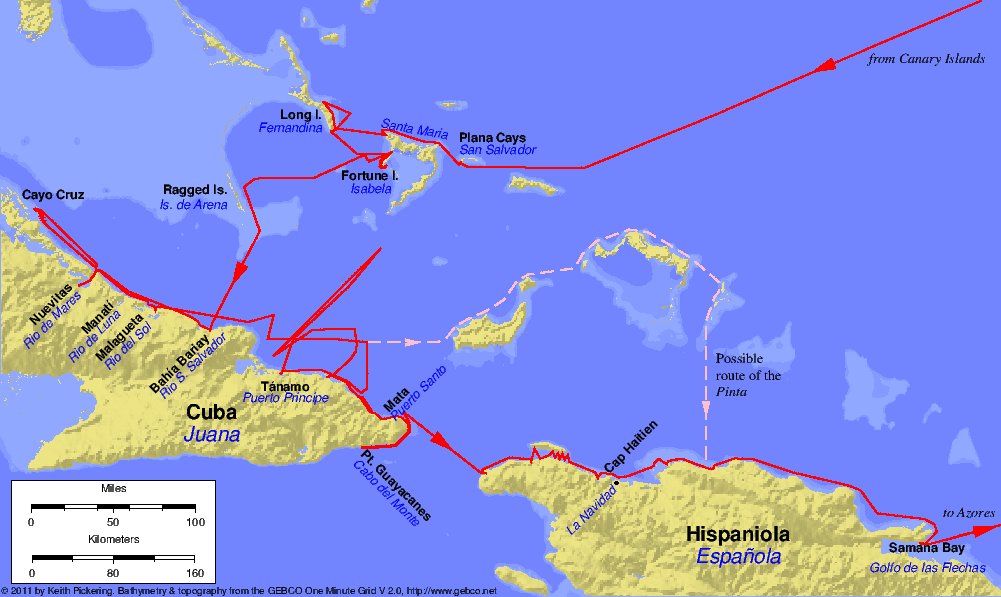

Even though he had made huge navigational mistakes and entirely missed the significance of Viking legends, Columbus did get one thing right. Traders who had plied sea routes in the open Atlantic were aware of the wind patterns of that ocean. From the Canaries, the prevailing winds are easterlies. These winds would quickly take the Columbus fleet far out into the Atlantic. But the terrifying thought for crews on Columbus’ little boats was that on the return voyage the wind would be against them.

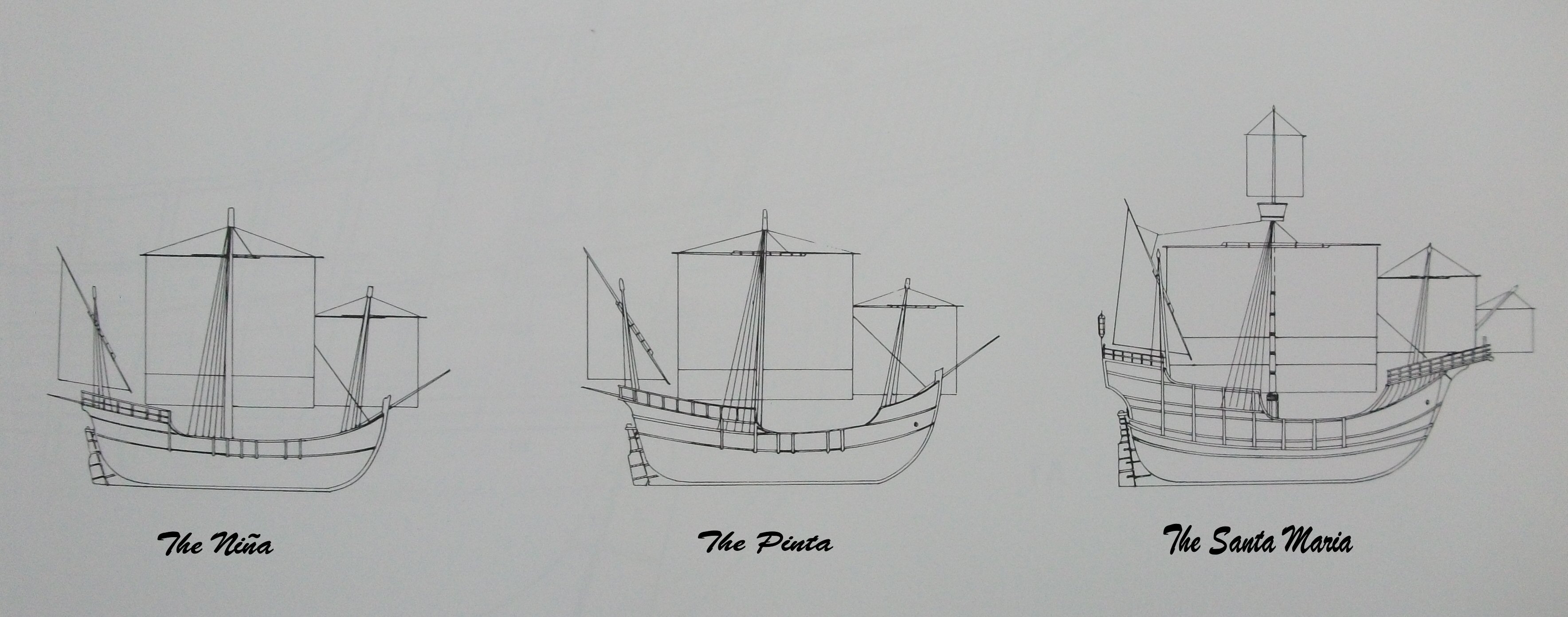

The only way for his ships to sail against a prevailing wind was by tacking, which involved arduous zig-zagging and changing the set of the sails at the end of every leg. Modern yachts are fore-and-aft rigged, and can sail to within 45 degrees of a headwind, but square rigged sailing boats could only achieve a fraction of this. The boats that he had were all square rigged. He had changed the Lateen rigged sails of the Niña to square rigged because he had a good idea that he would not need to tack so much, and square rigged boats would make better speed with a following wind. Columbus’ secret weapon was that he knew that if he navigated to the North Atlantic, where the prevailing winds were from the west, they would carry him home to Northern Spain. Only a decade later, when crossing the Atlantic became commonplace, these circulatory winds would be known as the trade winds. But when Columbus sailed they were relatively unknown.

Columbus’ fleet made good progress, and after four weeks of sailing were beginning to enter truly unknown waters now, and the worst fear for any mariner is to come upon shallow water or a rocky shore in the night or in a storm. Some of the crew were beginning to question the wisdom of letting the prevailing wind drive them into hazardous waters. Mutiny, never far from the crew’s minds, was beginning to show itself.

Columbus had kept two charts from the beginning of the voyage; one to show the crew, and one showing their real position. After each day’s progress he noted the distance covered in the real log but wrote a lesser distance in the log for the crew to see. He did not want them to see how far from home they really were. Columbus made a display of taking readings with his quadrant and was happy to reassure the crew by explaining his navigation. He of course had a magnetic compass, although during the voyage, Columbus noted a magnetic deviation of 11.25 degrees west; the first time that this phenomena had been seen. Sighting the Pole Star through the quadrant would give his latitude above the equator. This was important. He did not want to stray too far south and miss China, which was at the same latitude as his starting point of the Canary Islands. He could stray north, which would bring him to Japan at the same latitude as mainland Spain. Staying between these two parallels was essential.

Map of Columbus' course taken from his logs. Map from The Ships of Christopher Columbus by Xavier Pastor.

He had kept a log of speed by dropping a wooden float on a rope which had knots tied in it at measured distances. By counting the knots reeled out as the float passed a mark on the ship’s stern they knew their approximate speed. Last of all, the job of the cabin boy was to turn the hourglass in the Captain’s cabin and note the hours in the log. With these four pieces of information Columbus could navigate by what is now called “dead reckoning,” and he was first among sailors of the time to keep a complete record of all his calculations. It’s from these logs we can chart his progress today. On this first voyage westbound, Columbus stuck to his (magnetic) westward course for weeks at a time, and only departed from it three times; once because of contrary winds, and twice to chase false signs of land southwest.

Celestial navigation was just being developed by the Portuguese, and Columbus tried his hand at tracking his position using sightings of the stars. On his first voyage he made at least five separate attempts to measure his latitude using celestial methods. Not one of these attempts was successful, sometimes because of bad luck, and sometimes because of Columbus’ own ignorance of celestial navigation.

By the first of October, Columbus records that his “pilot”, who could only be Juan de la Cosa, had begun to question his records of the distance covered. After a rainstorm that lasted most of the day Columbus was challenged about his log entries. Remember that Juan was an accomplished cartographer and navigator, and was watching everything that Columbus did. Juan claimed that the fleet had covered more distance than the admiral was recording. He was right; Columbus made a show of displaying his charts showing that the fleet had covered 584 (2016 miles.) leagues since leaving the Canaries, but his own secret log records 707 leagues (2440 miles).

Nevertheless, the crews on all three ships were unhappy, afraid, and ready to mutiny. The mood lightened considerably when after 29 days out of sight of land, on October 7, 1492, the sailors spotted “immense flocks of birds" and Columbus changed course to follow their flight. Several of the birds were trapped by the crew who determined that they were land birds. (Probably American golden plovers) The following day brought more unrest from the crews and the admiral was forced to placate them with promises of fabulous wealth to come. On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet’s course to due west, and pressed on through the night, believing land was soon to be found.

Queen Isabel had promised the prize of an annuity of 10,000 maravedís to whoever should be first to see land, and La Pinta, being the fastest boat of the three, forged ahead hoping to collect the reward. At two in the morning, a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) yelled that he had sighted land. La Pinta’s captain, Martín Alonso Pinzón, verified the land sighting and alerted Columbus by firing a lombard. (A small cannon.)

Meanwhile, on the Santa Maria, Columbus’ log shows that four hours earlier, at 10pm the previous evening, the Admiral had seen a light "like a little wax candle rising and falling" and called Pedro Gutierrez Groom, who had served in the court of King Ferdinand, to confirm the sighting. He also asked Rodrigo Sanchez de Segovia, whom the King and Queen sent with the fleet as Inspector, to verify what they had seen. Their opinions differed, so Columbus called the crew together to say the Salve and ordered a special watch to look for land from stern forecastle. When the call came from La Pinta a few hours later, Columbus ordered the furling of sails and the fleet stood off until daylight.

Landfall map by Keith Pickering.

(Modern sailors have tested Columbus’ claim by taking a boat to the position where he noted that he saw the light, whilst others lit a fire on the highest point of Plana Cays, the modern name of the island. True enough, the fire could be seen in the night, but it still does not prove that Columbus did not fiddle the log. However, you have to remember that Columbus’ son had possession of his father’s logs long after his death, and he may have removed or added parts. For instance, there is hardly any mention of Juan de la Cosa, the man closest to Columbus during the voyage, and the rightful captain of the Santa Maria. It is only after the voyage the captain’s true significance was revealed.

On the morning of Friday October 12, the three ships cautiously approached the shore. The lookouts saw natives on the beach and in the forest along the shore, and Columbus ordered that the men who could use them be issued with swords and firearms.

Columbus had a speech prepared for the respected witnesses supplied by the Queen and King of Hispania who were on hand to record the event. The captains of the Pinta and Niña, Alonso Pinzon and Vincente Yafiez boarded the dory carrying the royal banner, a green cross on white background with the letters F and Y surmounted by the crown of each kingdom in the upper quarters of the standard. They were accompanied by Rodrigo Descoredo, Notary of all the Fleet, and Rodrigo Sanchez of Segovia with a handful of armed soldiers.

A woodcut of the landing by Theodor de Brey.

Once upon the sand, Columbus fell to his knees and thanked God for a safe arrival and a successful voyage. When he had regained his composure, he called the witnesses to him and gave his carefully prepared speech in which he claimed to all that he was taking possession of these islands in the name of the king and queen. The witnesses solemnly gave their testimony and duly recorded it in their own personal diaries to show the king and queen upon their return to Spain. All the years of planning and doubt had vanished when he stood upon the sand of that island. He had earned his title of Admiral of the Oceans, but in reality his troubles were just beginning. Not least of which were the dozens of naked savages who had silently walked from the surrounding jungle and now surrounded them.

1

Like

Published at 8:23 AM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 8:23 AM Comments (1)

The suicide voyage

Friday, November 12, 2021

In early May 1492, Columbus, a newly appointed admiral in the Royal Spanish Navy, showed up at the port of Palos under orders to conduct an expedition westward looking for a route to the Indies. He had with him letters of introduction signed by Queen Isabel of Castile which instructed the port authorities to impress a squadron of three caravels with supplies and crews who thereafter would serve in the navy at regular seaman’s pay. Two of the caravels were to be selected by the port authorities, but the flagship and its captain were to be selected by Columbus.

The sailors of Palos knew about Columbus’ insane mission and wanted none of it. The orders given to Columbus by Queen Isabel stated that he should be given “every assistance” to organise his ships and crews. Isabel even set a time limit upon how long it should take. She allowed the authorities ten days to comply. Ten weeks after he arrived, Columbus was still not ready to sail. He did not have time or money to browse the nearby ports to select ships, and was obliged to accept whatever they gave him. Eventually, the port authorities impressed the Niña and the Pinta, quite small caravels with a single deck each.

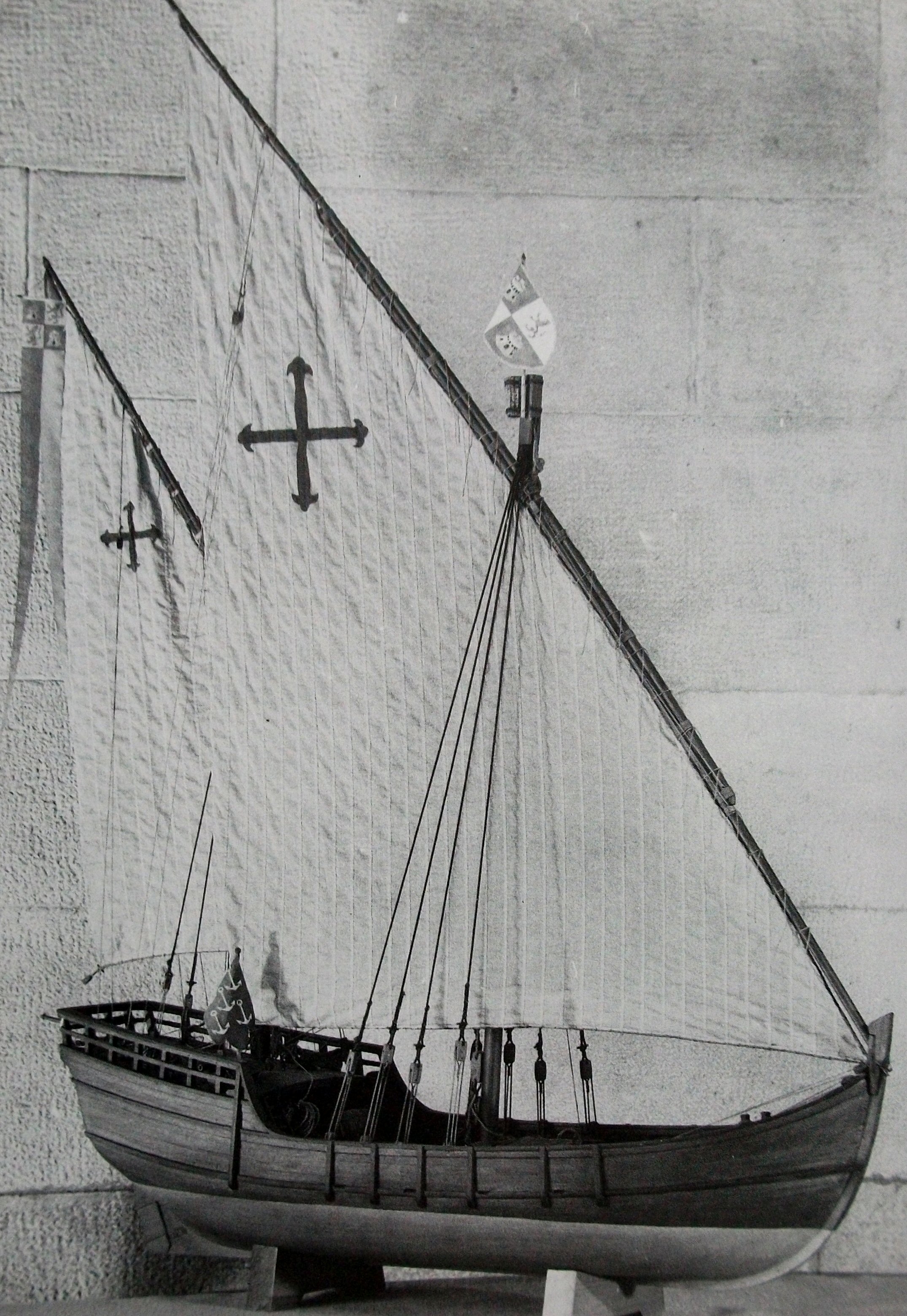

Photo Niña: Museo Maritim, Barcelona. Shown here before her lateen rigged sails were changed to square rig.

It was customary in those days to name your ship after a saint, and the Niña was actually called the Santa Clara; Niña was a pun on the name of the owner, Juan Niño de Moguer. On Columbus' first expedition, the Niña carried a crew of 26 and was captained by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón.

Photo: Pinta, Museo Maritim, Barcelona.

Martín Alonso Pinzón, brother of Vicente, captained the Pinta, and both were respected and well known captains from Moguer in Andalucia. Columbus now had to choose a flagship for his little fleet and find a captain willing to command it. This simple task would not be easy. The crews of all the ships were officially volunteers, but none of them wanted to sail on this voyage, and they showed it with non-cooperation and complaints before they had even left port. Their problem was that Columbus reported to the queen, and in effect had absolute power over all.

Exploration in the late 15th century was in the hands of a small class of veteran mariners who knew each other and shared information on navigation and were constantly updating their charts. Mariners who found new islands or ports made their own hand-drawn charts called portolan charts. Whenever a mariner returned from a voyage, he checked in at the office of the chief navigator, who would be a captain or other officer, to add his portolan charts and see what was new on the Mappa Mundi, the world chart that was constantly being updated by professional cartographers. One such office was in Puerto Santa Maria near Cádiz, and it was overseen by Juan de la Cosa.

It was while Columbus was looking around for a ship and a captain for his perilous voyage that he met Juan de la Cosa, who was visiting Palos at the time. Juan had his own ship, a nao called the Santa Maria, which was not exactly what Columbus was looking for, being slower and broader on the beam than the other two ships, but it came with a captain with impeccable credentials. The origins of Juan de la Cosa are obscure and confusing. It seems that he was originally from Galicia, and the high proportion of Galicians in the crew of the Santa Maria would support this, but in later correspondence with the crown over payment for his crew and the loss of the Santa Maria, he is recorded as a vecino of Santa Maria del Puerto, which is not the same El Puerto Santa Maria across the bay from Cádiz.

Photo Santa Maria. This is the 1927 replica near Huelva as reconstructed by Guillén. Photo: The Manuel Ripoll collection.

Columbus wasted no time in recruiting Juan and his ship. His expertise as a captain was beyond question, but it was his navigation and map-making skills that set him apart from other captains. If new lands were discovered he would need Juan’s skills to record them as evidence to present to the queen. As an admiral, Columbus would not actually do any sailing. The protocol, which went back to Roman times, was that the admiral commanded the fleet, but individual captains were in command of their own ships. The relationship between Columbus and Juan de la Cosa became strained from the start because Columbus constantly interfered with Cosa’s orders, and this would lead to problems later on. Finally, with his ships loaded, Columbus left Palos de la Frontera on 2 August 1492 and sailed down the Rio Odiel on the ebb tide to the Saltes sandbar. They anchored there for the night, and at 8 o’clock the following morning, with a favourable tide behind them, they set course for the Canary Islands.

The passage to the Canaries took six days, and by before they reached the coast of Africa the Pinta required jury-rigged repairs to her rudder. In his voyage notes, Columbus wrote that he suspected sabotage by its owners, Gomes Rascon and Cristo hal Quintero, who were unhappy that their boat had been requisitioned against their wishes. These two had already been stirring up trouble in Palos before the fleet had left. However, the admiral had every confidence in the Pinta’s captain Martin Alonso Pinzón whom he spoke of as “a brave and intelligent person.” Nevertheless, as the short voyage progressed, the hull of the Pinta began to leak and Columbus had serious doubts as to whether the boat was capable of an Atlantic crossing.

It became clear that they would have to stop at the Canaries and either make lasting repairs or hire another boat. They sailed to Gran Canaria and the port of Las Palmas, where the Pinta left the other two ships and docked at the small port of Gando which had facilities to repair the Pinta’s rudder. Meanwhile, the Santa Maria and Niña continued on to Gomera where Columbus ordered the conversion of the Niña’s lateen rigged sails to square sails which would be better for open-ocean travel. Both ships then returned to Gran Canaria to join the Pinta, whose rudder had now been repaired and her hull caulked.

Drawings courtesy of Xavier Pastor from his book The Ships of Christopher Columbus.

The united fleet sailed the 90 miles to Gomera, where they docked and took aboard final provisions for the voyage. It was whilst he was in the harbour at Gomera that a caravel arrived from Hierro bringing the news that three Portuguese caravels were patrolling the islands looking for Columbus' fleet. Because he had heard that Isabel had funded his voyage, the jealous and avaricious King of Portugal had ordered their capture, no doubt to offer Columbus a different contract of employment, or incarceration.. With no time to waste, before sunrise on the morning of 6 September, all the crews heard Mass together, and as the sun was rising, they left Gomera going west. To add to Columbus’ disquiet, the wind immediately dropped, and the fleet was becalmed in sight of Gomera and began drifting towards Tenerife on the current. It must have been an unnerving afternoon, because Mt. Teide had been erupting pretty much constantly during their stay, and there was nothing that they could do to halt their drift towards the volcano. At three in the morning of the 8th, the wind freshened from the northeast and brought with it a heavy sea, and the little fleet finally began to make slow headway to the west.

The first and subsequent voyages of Columbus are considered as, to quote a much later adventurer, “a giant leap for mankind.” There have been several events to celebrate the voyage. The first was in 1892 on the 400th anniversary of the first crossing.

A full-size replica of the Santa Maria was built by La Carraca shipyards in Cádiz under the direction of a Commission presided over by Captain Cesáreo Fernández-Duro. There were no plans of the original Santa Maria, and the builders only had Columbus’ notes to work from, but the Santa Maria was a nao, which was a very common type of vessel in use at the time.

The plan was to sail her to the World Trade Fair at Chicago, and when finished, she was towed to Palos de Moguer and symbolically left port on 3 August (The same date that Columbus sailed on.) escorted by two lines of warships from different nations. Unfortunately, it was found that there were errors in her design that would make an Atlantic crossing dangerous, and she was towed back to Cadiz for alterations. Finally, on 10 February 1893, she set sail for the Canaries, where she stopped at several ports before leaving Santa Cruz de Tenerife on the 22nd bound for America. She reached San Juan de Puerto Rico on the 30 March after thirty-six days of sailing. (One day less than Columbus took.) From there she sailed to New York, Quebec, Montreal, Charlotte and Toronto, finally reaching Chicago on 17 July 1893.

It was 1927 before another attempt was made to construct a replica of the Santa Maria. During the intervening years since the first one had been constructed, Julio Guillén, a Lieutenant in the Spanish Navy, had published a book named La Carabela Santa Maria. He had researched the old records and proposed that the Santa Maria had been a carabela de armada and not a nao. The 1892 replica had been a hybrid of the two different types of vessel and whilst each type had proven to be seaworthy, mixing the two types of design had caused problems. The construction of a new replica was begun in the Echevarrieta shipyard in Cádiz. The new Santa Maria was exhibited at the Exposicion Iberoamericana de Seville in 1927 and was later anchored off the monastery of la Rabida in Huelva. Sadly, in 1945 she was being towed from Valencia to Cartagena for repairs when she sank. Guillén was later to become Director of the Naval Museum in Madrid and a member of the Academia de la Historia, during which time he wrote several books on naval history.

The most bizarre episode concerning Columbus’ voyage began when José Martinez Hidalgo y Terán, a Commander in the Spanish Navy, and Director of the Museo Maritim de Barcelona for 20 years, asserted that the Santa Maria was a nao, and his meticulous research led to the construction of another replica to be exhibited at the New York World Fair of 1964/5. She was built by the Astilleros Cardona, and when completed, was loaded onto the German freighter Niedenfield in Barcelona. The Niedenfield took her to Mench’s Boulevard, Flushing, where the 80 ton ship was loaded onto a road transporter and driven the three miles to the exhibition site. This involved the transporter with its 90 ft. long load passing through the Queens District of New York. Escorted by a flotilla of police cars and with technicians taking down telephone wires and cutting back trees along the route, the Santa Maria was finally lowered into Meadow Lake, where she was moored for the exhibition.

Lastly, in 1992 construction began of replicas of all three ships which then sailed together along the route that Columbus took. They are now displayed in the Muelle de las Carabelas (Wharf of the Caravels) in Huelva. (Another place that I am going to visit post Covid.)

1

Like

Published at 10:05 AM Comments (4)

1

Like

Published at 10:05 AM Comments (4)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|