When Columbus’ ships beached themselves in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, on 25 June 1503 his crews were tired and disillusioned. Columbus had been suffering from ill health ever since the return voyage on the first expedition. During the height of a storm he had suffered an attack of what he thought was gout. During subsequent voyages he suffered further bouts coupled with fevers, bleeding from the eyes and temporary blindness. Add to this the problem that his crews were not the most congenial of companions to be marooned with.

He still had friends, and the man who had been assigned to Columbus as personal secretary, Diego Méndez de Segura, together with Bartolomé Flisco, a Spanish crewman, took one of the large native canoes and six natives and set out to across the 150km. wide Jamaica Channel to reach Hispaniola. It’s not clear whether they finished the last 450km.to Santo Domingo by land or sea, but the result was that the governor, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres was indifferent to their pleas for help. Cáceres was deeply jealous of Columbus and he prevaricated with preparations to rescue him. Weeks turned into months, and the rescue preparations had not progressed despite the constant pleading of Segura.

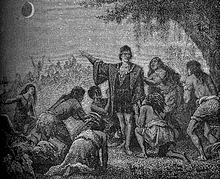

On Jamaica, the 250 men with Columbus were dependant on the natives for food and water and Columbus and his brother, Bartholomew, struggled to keep the crewman in line. They kept order for seven months, but the natives were uneasy with these strangers who kept promising that they were going to leave soon, and they became restless and threatening. This is where Columbus’ self-education paid dividends. His celestial navigation was not too good, but he had with him an Ephemeris compiled by the German astronomer Regiomontanus, which gave dates, times and positions of celestial events. One of these events was a lunar eclipse, which was due to happen on the night of 29 Feb 1504. Columbus called a meeting with the chief of the local tribe and told him that if they did not continue helping them he would extinguish the light of the full moon. He had picked his time carefully, and when the chief scoffed at his threat Columbus told him to call his tribe together to watch the moon with him that night. Of course, Columbus knew the exact hour that the eclipse would begin, and he made a show of calling to the heavens to strike out the moon. The natives were impressed when the moon dimmed, and Columbus made them promise never to doubt his word again or go against him. Then, with a wave of his hand and some arcane words the moon gradually returned to full brightness.

Controlling the mutiny in his crews was not so easily accomplished. The ringleaders were the Porras brothers, who were planning to overthrow Columbus and take control of the ships. Eleven months after they had become stranded on Jamaica open rebellion broke out, and Bartholomew Columbus had to defend his brother in a swordfight with Francisco de Porras. Bartholomew eventually got the better of Porras and spared his life, but unless help came soon there would be blood spilled. Finally, on June 29, a caravel sent by Diego Mendez arrived from Santo Domingo to take the crews back to Hispaniola. Even then, the bad luck that had dogged Columbus on his final voyage had not run its course. The wind became strong from the south-east and the ship made little or no headway. The journey to Hispaniola took 45 days and of those 110 sailors who landed in Santo Domingo, only 72 wanted to continue home to España. Columbus and his son Fernando paid their own passage and arrived at Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 7 November 1504, and from there they made their way to Seville where they settled. Columbus was by now suffering from frequent bouts of fevers and illness that left him bedridden for weeks.

The previous year, Juan de la Cosa had arrived from the Caribbean to find that his Mappa Mundi had been taken to Portugal some three years earlier by Vespucci and had never been seen since. His map had been for the benefit of all mariners, and it was they who provided new information to update it with. De la Cosaa was furious that somebody would take the map and the information it contained for their own private gain; that it was no less a thief than the King of Portugal did not matter. He set off in pursuit of his property and arrived in Lisbon in 1503, but as soon as the authorities knew that he was making inquiries, he was promptly arrested and imprisoned. A series of letters followed between the crown of España and Portugal, and Vespucci finally agreed to return the map. It was a pointless exercise; the map was hopelessly out of date by now and had been copied, updated and distributed to Portuguese mariners. De la Cosa’s Mappa Mundi was returned to the office of Rodríguez de Fonseca, where all trace of it was lost until the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was discovered in a Paris junk shop by Baron Charles-Athanase Walckenaer. It was only identified as an important historical document in 1832 by the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. The map was purchased by the Spanish government in 1853 and is now in the Naval Museum in Madrid. Juan de la Cosa sailed with Ojeda again in 1509 to take possession of the coasts of modern Colombia, but he and his men were surrounded by natives and all were killed.

Queen Isabel had died in 1504, and the monarchy was in turmoil. Isabel’s oldest daughter, Joanna, was now next in line to be Queen of Castile, but Archduke Phillip, her husband, who would have become King Phillip I, died in 1506. Ferdinand proclaimed himself Governor and Administrator of Castile. He declared Joanna insane, and continued to rule as regent until his death in 1516.

Undaunted, Columbus continued to pursue his case for the unpaid royalties which had been promised in the contract that he signed (The Capitulations of Santa Fe) with Isabel and Ferdinand. The contract stated that he be paid “one tenth of all the riches and trade goods yielded by the new lands.” The crown argued that since he had been removed as governor of Hispaniola, he was no longer entitled to claim them. The royal court moved to Segovia, 500 km. from Seville, and Columbus was obliged to make the arduous journey there by mule to continue his case. Ferdinand married Germaine of Foix in Valladolid in March 1506, and they set up a new court there. Columbus, now 56 years-old, doggedly followed them to Valladolid to continue petitioning the crown for his entitlements. But the voyages, and his betrayal by the crown of España, had taken their toll on his health, and he died in Valladolid on May 20 1506.

During his later years he had written two books with the assistance of his son Diego and his friend the Carthusian monk Gaspar Gorricio. The first was the Book of Privileges published in 1502 detailing the promises and contracts that the crown had made with him when they granted him funding for the first voyage. The second was The Book of Prophecies (1505) which quoted passages from the bible as prophecies of his voyages of exploration. His heirs continued to sue the crown after his death in a long series of legal disputes known as the pleitos colombinos (Columbian lawsuits).

These two publications are Columbus’ testimony of his betrayal. They represent his bitter recriminations against the established hierarchy of the nascent country of Spain, where the privileged aristocracy and the church ruled. But the church was about to suffer a schism that would rock it to its foundations. In 1517 Martin Luther hammered to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg his “ninety-five theses of discontent” with the Catholic Church. (Posting notices in this way was the recognised way of inviting discussion.) Sixteen years later in 1533, Queen Isabel’s youngest daughter, Catherine, would fail to provide King Henry VIII with a male heir, and when the pope refused to give him a divorce, Henry declared himself head of the protestant Church of England.

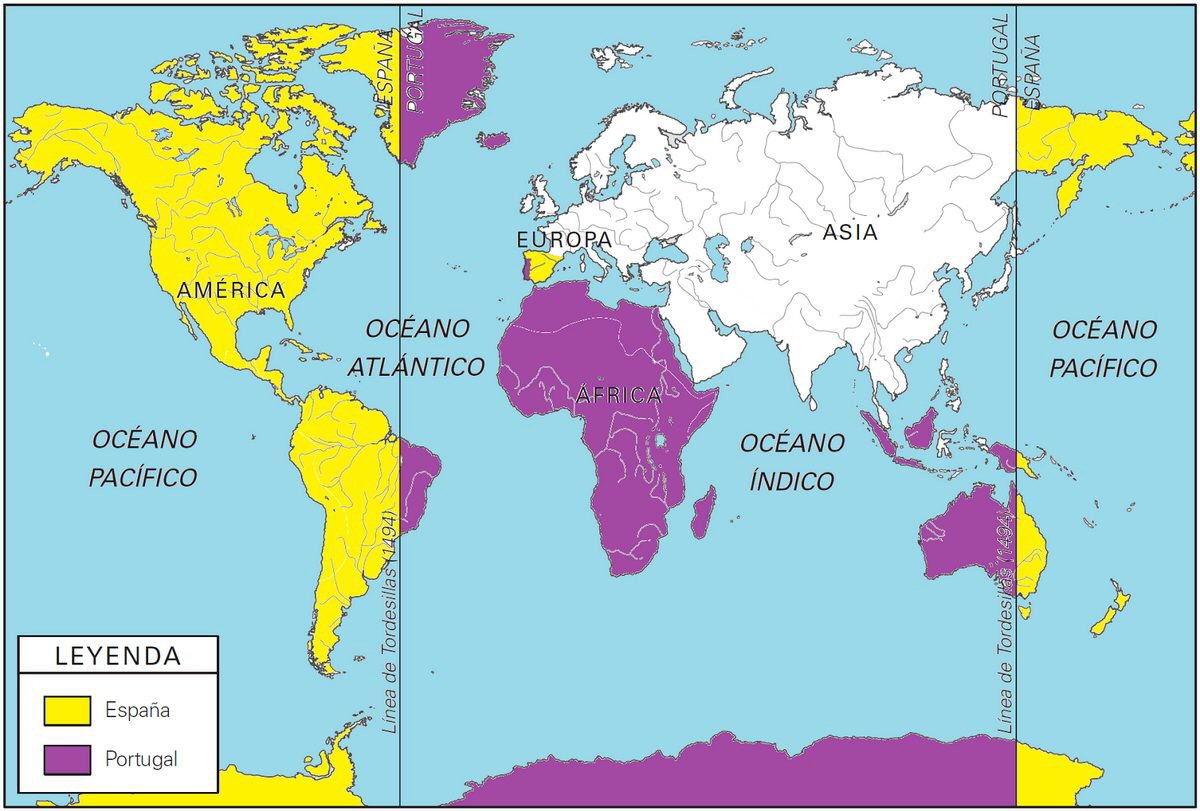

At some point during this period, to avoid further tension between España and Portugal, and with absolute arrogance and consummate ignorance of the native inhabitants of rest of the world, the Tordesillas line was carried on through the poles to divide the planet in half; one half owned by España, and the other half owned by Portugal.

Neither the Portuguese or Spanish explorers had found any signs of a superior civilisation anywhere they landed. (Except for the initial landings in the Indies, which was as near to an ideal society as humanity has ever produced.) Iron, steel, gunpowder and oceangoing ships were unknown in the new world. Given the history of the Mediterranean civilisations, subjugation and near extermination of the native population was inevitable. The brutality of the conquest of the Americas and the following importation of slaves from Africa is one of the darkest periods in world history. But I am not going to go there.

When I started these blogs at the beginning of Covid lockdown it was because I had become very interested in Spanish history during the eight years that I lived there. I wrote two fictional books set in medieval Spain and published them. I have also been (and still am) painting aviation art, amongst other subjects. Nearly all of the blogs have been about wars. For Spain, the Roman occupation and Numantine Wars were followed by the Islamic invasion and reconquest. Later on came the French invasion and Spanish Civil War.

Spanish soil is steeped in the blood of a thousand generations of people who fought to defend it against invaders. But the history of Europe is 10,000 years of nearly constant warfare, and just when we thought that two World Wars would have put an end to it, we now have the horror of the Ukraine. I believed that it was only by looking at the past that we can avoid making the same mistakes in the future, but I see that I am wrong. Malicious, sick, psychotic people exist at all levels of society and it is only by standing up to them that the world can improve.

Spring is here, and the Covid plague has seemingly passed. I am going to stop blogging for a while and visit some of the places that I have been blogging about. I have enjoyed writing these blogs and it has been very educational for me. I would like to thank the editor at Eye on Spain for his support, and the 71,000 people who have been reading them over this period. I am not going away, but I will post less frequently than I have been doing. Thank you for your support.

Alan Pearson.