Be careful who you ask for help

Saturday, September 26, 2020

The vicious civil war amongst the ruling Umayyad taifas in al-Andalus had debilitated them and culminated in the destruction of Córdoba and the Shining City. However, King Alfonso VI of Castile and León was still as big a threat as ever, and would certainly take advantage of this weakness. Sure enough, the taifa of Seville soon came under threat from Alfonso’s forces. After the fall of Toledo to Alfonso in 1085, its caliph, al-Mu'tamid, had launched a series of aggressive attacks on neighbouring kingdoms to amass more territory for himself, but in the end he was still vastly inferior to the Christian forces.

He consulted with his advisors about asking the Almoravid caliph in Marrakesh, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, for his help. If he were to be conquered by the Christians, he would be forced to pay a humiliating jizya (tribute) that would cripple his caliphate. His son, Rashid, was more outspoken and he railed against inviting the Almorovids into al-Andalus. His father answered with the famous speech.

“I have no desire to be branded by my descendants as the man who delivered al-Andalus as prey to the infidels. I am loath to have my name cursed in every Muslim pulpit. And, for my part, I would rather be a camel-driver in Africa than a swineherd in Castile.” In their haste and fear, they made a huge error and sent envoys to Marrakesh asking for help.

We have been watching events in Iberia, but North Africa had undergone its own revolution. Western North Africa had been made up of a number of separate tribes, but a Gazzula Berber leader named Abdallah ibn Yasin rose to prominence and united them. His name is a clue to his origins, "son of Ya Sin" suggests that he had obliterated his family past and was "re-born" of the Holy Book, meaning that he was probably a convert to Islam rather than born to the faith. He was a puritan zealot, characterized by a rigid formalism and strict adherence to the dictates of the Qur'an, and Orthodox tradition. Other Berber tribes often referred to them as the al-mulathimun (the veiled ones) because of the tagelmust, a veil which covered their lower face below the eyes. Present day Tuareg people still wear them, and though highly practical in the dust of the desert, the Almoravids insisted on wearing them everywhere as a way of emphasising their puritan brand of faith. Under their law, those not of their creed were forbidden to wear the veil, and so in al-Andalus, it served to distinguish them as the ruling class. The Umayyads considered them to be fanatical barbarians, but they knew that without Almoravid help, the Christians would have stormed through al-Andalus.

The Almoravids, led by Yusuf ibn Tashfin crossed the straits to Algeciras, and from there to Seville, where they set up a base camp. Tashfin was joined by the caliphs of Málaga, Seville and Granada, and their troops marched as one army to Badajoz, where they were joined by the troops of that taifa. The Muslim army now numbered between 60,000 to 80,000 men.

Outnumbered 20 to 1, Alfonso opened peace negotiations. Tashfin offered to allow the Christians to convert to Islam, pay a crippling tribute, or fight. Alfonso chose to fight. At dawn on the morning of October 23, 1086 the Christians charged and sacked the camp of one of the taifas, killing several of their leaders. By the afternoon however Alfonso was encircled by the superior forces, and the battle was clearly lost. By the evening, half the Christian army lay dead on the battlefield. The losses were heavy on the Muslim side, too, and this prevented the Moors from capitalising on their gain. Castile had not lost the psychologically important city of Toledo, and many of the taifas had lost so many leaders and troops that it would take months to rebuild their armies. At this crucial time, Tashfin had to return to Morocco because his oldest son and heir had died. Now known as The Battle of Sagrajas, it took its name from the Arabic description of the battlefield, az-Zallaqah, or "slippery ground" because the warriors had difficulty fighting on the bloody soil.

Yusuf ibn Tashfin returned to al-Andalus in 1090 and was dismayed by what he saw. The lax behaviour of the taifa kings, both spiritually and militarily, struck him as a breach of Islamic law and principles. Even before the invasion, he had been writing to the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad about extending the Orthodox Qur'an to al-Andalus with the clear intention of, "The spreading of righteousness, the correction of injustice and the abolition of unlawful taxes." The caliphs in such cities as Seville, Badajoz, Almeria and Granada had grown accustomed to the extravagant ways of the west. On top of doling out tribute to the Christians and giving Andalusian Jews unprecedented freedoms and authority, they had levied burdensome taxes on the populace to maintain their lifestyle.

That year, Tashfin exiled the caliphs Abdallah and his brother Tamim from Granada and Málaga. A year later, al-Mutamid of Seville suffered the same fate. Yusef united all of the Muslim dominions of the Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Zaragoza, to the Kingdom of Morocco, and situated his royal court at Marrakech. He took the title of Amir al-muslimin (Prince of the Muslims), seeing himself as humbly serving the caliph of Baghdad, but to all intents and purposes he was the caliph of the western Islamic empire. The military might of the Almoravids was at its peak.

The Almoravids had gained little ground from the Christians, but one city above all others offended Tashfin’s sensibilities. Valencia was the home to Muslims, Jews and Christians, and under the weak rule of a petty caliph who was paying a jizya to the Christians, chief of whom was the famous El Cid. However, Valencia proved to be a stubborn obstacle for the Almoravid military. Tashfin led his fourth campaign against the Christians in 1097 when he tried to fight his way to the practically abandoned, yet historically important, Toledo. On August 15, 1097, the Almoravids delivered a blow to Alfonso’s forces, with a battle in which El Cid's son was killed. The war had become personal.

Tashfin appointed his son, Muhammad ibn’ A’isha, as governor of Murcia, and he laid siege to El Cid's forces at Alcira. The city didn’t fall, but Tashfin was satisfied that the Christians had been brought to heel, and he left for Marrakesh. He returned two years later and renewed his campaign in 1099. El Cid had died in the same year, and his wife, Jimena, had been ruling Valencia with the aid of King Alfonso. Tashfin ordered his lieutenant, Mazdali ibn Tilankan to lay siege to the city, and after a seven-month standoff, Jimena burned down the city’s great mosque and abandoned Valencia to the Moors.

Even though Yusuf ibn Tashfin was Caliph of al-Andalus and all Morocco and had conquered the home city of El Cid, the Christian hero, it is El Cid who is remembered in Spain’s oldest epic story, Poema del Cid, or El Cantar del Mio Cid.

Worse was to come for The Prince of the Muslims. His dynasty would only last another 47 years. In his homeland of Western Africa, in the Atlas Mountains, another Muslim faction was growing and gnawing at the Almoravid’s power base. The Almohads led by Ibn Tumart had begun their climb to ascendancy.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

El Cid, the freelance warrior.

Saturday, September 19, 2020

Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar: El Cid

.jpg)

This statue of El-Cid stands in Seville on El Parador de San Sebastian next to the Plaza de Espña. It is one of 5 editions sculpted by Anna Hyatt Huntington in 1927. The others are located in Valencia, Lincon Park San Francisco, Balbao Park San Diego and Buenas Airies, Argentina. She also sculpted the four Castilian warriors around the statue.

Whilst the looters were still ransacking the remains of The Shining City, a young boy born to minor nobility was working in the court of King Ferdinand I of León under the wing of one of his sons, Prince Sancho. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar showed his military abilities from an early age. In 1057, Rodrigo fought with Sancho against the Moorish stronghold of Zaragoza, making its emir, al-Muqtadir, a vassal of the king. In the spring of 1063, he fought in the Battle of Graus, where Ferdinand's half-brother, Ramiro I of Aragon, was laying siege to the Moorish town of that name. Al-Muqtadir, aided by Castilian troops including El Cid, fought against the Aragonese. During the battle Ramiro I was killed, and the fight turned into rout. One of the stirring legends surrounding El Cid was that during the conflict he killed an Aragonese knight in single combat, thereby receiving the honorific title "Campeador".

When King Ferdinand died in 1064, his will divided the kingdom between his three sons. Sancho’s brothers became Alfonso VI of León and García II of Galicia, and Sancho became king Sancho II of Castile. Sancho immediately began a series of campaigns during which he captured land from his two brothers as well as the Muslim kingdoms in al-Andalus. Rodrigo, grew in Sancho’s court and rose to become a military commander and the royal standard-bearer for Castile.

After the death of Ferdinand, Sancho continued to enlarge his territory, conquering the Moorish strongholds of Zamora and Badajoz. He also fought in many major battles against Sancho’s brothers, and his reputation grew as a general. But when Sancho learned that Alfonso was planning on overthrowing him in order to gain his territory, it was El Cid that he sent to bring Alfonso to his court so that Sancho could speak to him. The avaricious Alfonso evaded all charges made by his brother, but the jealousy between them increased and during a siege at Zamora, Sancho was lured into a private meeting and murdered. El Cid was now in the centre of a royal murder trial.

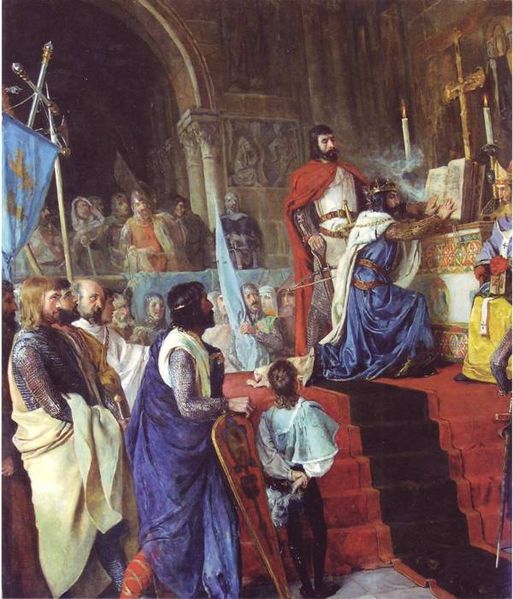

This depiction of the "Santa Gadea Oath" was painted by Armando Menocal in 1889 and is one of several paintings showing the famous trial. Armando was a native of Cuba, but came to Spain in 1880 where he discovered the work of Joaquin Sorolla and others. He exhibited in Spain winning several awards before returning to Cuba to become the director of the Academy of San Alejandro

Rodrigo was now in the difficult position of having bear witness against Alfonso who was accused of killing his own brother. Alfonso was cleared of the charges, and became King Alfonso VI of Castile and León, but Rodrigo was never fully trusted again, and was demoted in the new king’s court. He carried on serving the king for a while, but finally in 1081 he was forced into exile.

Allegiances had to be fluid to survive in those times, and Rodrigo went to fight for the Muslim rulers of Zaragoza, who were warring against the Christian states of Aragon and Barcelona. He distinguished himself as a general during campaigns against the Muslim rulers of Lérida and their Christian allies. It was around about now that he earned his Arabic nickname, al-Sayyid; the Lord. It was corrupted by Christian tongues into El Cid, and the name was carried into history along with the fame of Rodrigo.

King Alfonso strengthened his borders with the caliphates, which were organised into separate autonomous taifas led by local lords. Castile had the same system, where the fueros were administered by a local dukes, and Alfonso fed them arms and soldiers until they were ready to creep forward and take Muslim lands. He repopulated the cities of Segovia, Avila and Salamanca, but his biggest prize was the conquest of the taifa of Toledo. Alfonso was a very clever king, who used all diplomatic means to achieve his aims and only used force as a last resort. His taking of Toledo was over several decades, and Alfonso played the infighting lords of the Muslim city-states against each other and encouraged Christian settlers to move into Muslim lands until there was a mix of both living in the Muslim controlled city. The most powerful of the Islamic leaders was al-Quadir of Toledo, but he soon found that he was under attack from other Muslim states, and was forced to ally himself with Alfonso to defend himself from them. The inhabitants of Toledo, now sick of the constant power-plays, gladly allowed the Christians to “take” Toledo, even staging a fake siege to let everybody keep face. In fact, the capture of Toledo was entirely bloodless.

Toledo had been an important Visigoth city, and was still powerful under the Arabs. Its inclusion into Castile earned Alfonso great respect throughout the Christian world. He added Galicia and León to his kingdoms, and began a campaign to take Zaragoza, too. As his power and fame spread, he gave himself the title of Emperor of all Hispania instead of just King of Castile. His use of Hispania was the first time that the namehad been used in the context of a unified country of kingdoms.

The taifas were worried now about the Christian incursions into their caliphates. They were weak and disorganised after their own bouts of civil war, and asking for help from the Almoravids, though not entirely popular, seemed like a good idea. The Almoravids arrived and Alfonso met them near to Badajoz at the Battle of Sagrajas. Alfonso lost the battle, but retained all his lands. Unfotunately for the caliphates, they had allowed a greedy and very powerful emir and his army into al-Andalus.

Alfonso now realised that the game had just changed for the worse, and he needed all the allies that he could muster. Rodrigo was not easily bought, and began to strengthen his ties with the kingdom-city of Valencia, operating more or less independently of Alfonso. He began supporting the Banu Hud and other Muslim dynasties who opposed the Almoravids and gradually increased his control over Valencia. By 1092 the city was under his control, and the Islamic ruler, al-Qadir was forced to pay him parias, or tribute. The Almoravids by now controlled many of the smaller city-states and stirred up an uprising against El Cid. In the battle to regain control of Valencia, al-Qadir was killed and El Cid took control and created an independent principality with the full support of both Muslims and Christians.

When the troubled Muslim princes had asked the Almoravids to intervene on their behalf, they had made a big mistake. The Arab princes who ruled al-Andalus had been replaced by Almoravid leaders, and by 1094 the Almoravid lord, Ibn Tashfin, ruled all of Muslim Iberia.

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

Yes, but what did the Arabs ever do for us?

Saturday, September 12, 2020

My aim with these blogs about Spain was to show the art and writing of Spain during its history, but so far I have been talking mostly about warfare, and in the next few weeks I will be writing about 3 more waves of African invasion. But I want to stop here and take stock of where we are and maybe show you something better than warfare.

We have reached the first millennium after the birth of Christ, but peace on Earth was as far away as it was in Roman times. The Catholic Church covered Europe north of the Mediterranean, whilst Islam and the Arabs ruled its eastern and southern shores. The pope in Rome was now emperor of Christendom, and the Church was about to show its muscle.

From about 1020, with papal backing, the Normans invaded and captured Muslim controlled Sicily before going on through many campaigns to take control of the toe and heel of Italy, which had been under the control of the other half of the old Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire.

In 1066, again with papal encouragement, the Normans invaded England, which had been struggling with repeated Viking attacks, threatening to turn it into a pagan country. But in 1070, the Seljuk Turks took Jerusalem and began to torture the Christians who lived there. By 1095, the mistreatment of the Christians had become so bad that Byzantine Emperor Alexios I sent his envoys to Pope Urban II asking for help from western Christians to liberate the region from the Turks. Pope Urban II toured Gaul to encourage support for a campaign to free Jerusalem from Muslim control. He gave a historic sermon at the Council of Clermont when he exhorted the nobles to embark on the journey to "liberate" Byzantines, or Eastern Christians from the "pagan race." The First Crusade was underway.

We can’t look at the history of Spain without mentioning the other Abrahamic religion. Two of Rome’s emperors were from Italica in southern Iberia; Trajan and Hadrian, (Theodosius may have been a third emperor born in Italica, but it has been disputed.) and it was during the reign of Nero that the Jews first rebelled in 66. The Jews had lived in Canaan since the late second millennium BCE, but after the crucifixion of Jesus, the Romans tightened their control of the Jews in the area, and unrest against the Romans grew. Revolt erupted again in 132 led by Bar Kokhba, and it quickly spread from central Judea across the country, cutting off the Roman garrison in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem). Despite arrival of significant Roman reinforcements, initial Jewish victories over the Romans established an independent state over most parts of Judea Province that lasted two years.

Hadrian was emeror by this time and he gathered a force made up of six full legions to invade Judea in 134, and in the resulting battle 580,000 Jews perished, with many more dying later of hunger and disease. Many Judean war captives were sold into slavery and the Jewish communities of Judea were devastated to an extent which some scholars describe as genocide. In an attempt to erase any memory of Judea or Ancient Israel, Emperor Hadrian wiped the name Judea off the map and replaced it with Syria Palaestina. He further barred Jews from entering Jerusalem, and from then on they were a people without a homeland and were scattered to every part of the known world.

But amidst all this warfare, the seeds had been sown for a better future. The Caliphate of Córdoba had been the centre of learning and culture for around 100 years, far outshining any other European city. Its libraries were full of the books of Greek, Egyptian and Arabic knowledge, and for a while, it was the envy of the world. There were other centres of learning in Iberia which were gathering a reputation, too. Toledo and Granada had several libraries each, which in total contained some 3,000 books. In the century to come, Toledo would become a centre for the translation of the books written in Arabic and Greek into the new language that was forming from this mix of old-world tongues; Castilian.

The establishment of the first dedicated higher learning institution for teaching and study was to be in a very unlikely place. Initially founded as a madrasa or mosque in 879, Al-Karouine in the ancient walled city of Fez, attracted mathematicians, astronomers, philosophers and religious leaders to teach or study. The 12th century cartographer, Mohammed al-Idrisi lived in Fez around 1130 and travelled throughout the whole of the Mediterranean area. It was Idrisi’s maps that aided European exploration for the next 200 years.

Al-Karouine Al-Karouine

Bologna established its university 1086 followed by Oxford, England in 1096 and the competition to attract the finest minds to teach became fierce. The earliest Christian centre for teaching and study in Iberia was the Studium Generale in Palencia in 1212. It was endorsed by King Alfonso VIII of Castile, who was one of many kings who would encourage the translation of the abandoned Arabic libraries. In the first centuries of the new millennium, copies of Ptolomy’s star catalogue, the Almagest which had been lost to Christendom, turned up written in Arabic with corrections and additions by Al-Sufi, possibly the greatest of the Islamic astronomers. Al-Sufi's treatise on star cartography, or uranography, (published in 903) was called The Book of Constellations of the Fixed Stars (Kitab Suwar al-Kawakib al-Thabita) and became a classic of Islamic astronomy. It was al-Sufi who gave all the stars in the constellations the Arabic names they still bear today.

With the encouragement of subsequent popes other Studiums opened in Alcalá de Henares and Valencia, and masters who taught in one could go to any of the others and teach or study. But the most important thing about the Studiums, was that they were open to Christians, Jews or Muslims, without prejudice. In fact, all three aided in the translation of books left by the Moors. In the new Iberia, the Jews became leaders in medicine, and some of the Arabic legal statutes were adopted by Christian kings. Finally, it was an Arab, Hasan al-Rammah, a chemist and engineer working in the Mamluk Sultanate, who around 1250 made the first drawings of weapons which used gunpowder.

We all know that the lands around the Mediterranean have been a source of ambition, warfare and slavery, with empires rising and falling and constant bloodshed. But the most lasting impression of these times is in the architecture the Arabs left behind. The beauty of their buildings is beyond doubt, and even more impressive considering that most of Northern Europeans at this time lived in primitive huts. Perhaps with a little more time, peace could have been the outcome.

Even in the present day, there are those who are trying to bring about peace. The king of Morocco and the Junta de Andalucía came together 1998 to create a religious forum based on the principles of peace, tolerance and dialog. There are few organizations in the world that represent the three Mediterranean cultures of Islam, Catholicism and Judaism. Their aim is to find common ground for stability between these religions and they pursue it with dedication and openness. The Foundation has been endorsed by the Peres Centre for Peace, the Palestinian National Authority and other individuals and institutions in Israel, committed to promote understanding resolve conflict. They also have the support of the European Union, but clearly, this is an enormous task given present day tensions.

Their base is in Seville amidst the now disused Expo ‘92 exhibition buildings on La Isla de La Cartuja. At first sight, it looks as though it is put together haphazardly, as though the Lego that it was built from was a mix of two different building sets. But it is what is inside that is important.

The building itself is designed to recreate the Islamic influence evident all over Spain, but to modern standards. There is no thousand years of wear and tear here. It’s all brand new. The first view of the interior is very impressive, with a highly polished marble floor and a huge grey, eight pointed star inlaid with ceramic tiles in the centre of the room. Around the marble fountain are glass panels set into the floor admitting light to the floor below and permitting a view of the marble circular pool directly below the star.

The first floor is where the women would pray unseen from the men below. The women´s gallery is an illustration of the finest carpentry and painting as practiced by the artisans of antiquity.

Above this, is a wooden dome composed of beautifully painted timbers and highly polished panels.

Looking down from the woman's gallery, you can see the intricate and beautiful design of the ground floor mosaic and the glass panels designed to give the impression of still water. Below the glass, is the basement level, with a crystal stalactite dribbling water into a still pool. In a circle around this tranquil scene are beautifully decorated arches leading to side rooms for private prayer or meditation.

By comparison, the Alhambra and The Mesquite in Cordoba are undeniably impressive, but dulled by 700 years of use, the paint and carvings bearing the patina of smoky candles and oil lamps. The colours here are bright, clear and vibrant.

On the first floor, in corners off from the woman's gallery are carved ceilings with delicate painted scenes in astounding detail showing the mastery of Islamic art.

The foundation has a high ideal, but it’s in the right place. The straits have always been the hotspot for immigration or invasion, and if some respect and tolerance can be taught here, then the next thousand years might be better.

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (4)

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (4)

The warrior saint

Saturday, September 5, 2020

The north of Iberia had evaded the Islamic invasion primarily because of its mountainous terrain, which afforded the Christian defenders a wealth of hiding places and ambush traps for invading troops. Also, in winter, many of the high passes were closed by snow, and there were easier gains for the Moors and better pastures in the lowlands. The Romans thought pretty much the same, and they left the north west of Iberia alone, too. In fact, the Romans had called Galicia the “finis terrae” or the end of the world. To them, the Atlantic Ocean stretched off into infinity, and they believed that Galicia was where the souls of the dead rested before making the long journey to the afterlife. The encirclement by the Moors served to concentrate those of the Christian faith and strengthen their traditions and folklore. They were isolated, whilst Islam dominated most of Iberia and the holy land, the home of their faith. The future looked pretty bleak for Christians, and they needed something to rally around closer to home.

The Moorish forces led by Musa ibn Nusayr had already swept past the old kingdoms. Abd al-Rahman I took control of Arab forces in al-Andalus in 756 and consolidated his grip after his coup. The kingdom of Asturias was the strongest force in the Christian zone, and when its king, Alfonso I, conquered León and Galicia in 754, it became a safe haven for all the dispossessed Christians from the south. It was Alfonso who created the Desert of the Duero, a depopulated buffer zone between Muslim and Christian lands, so that invading armies would have to carry their supplies instead of looting them, and it was Alfonso who began the enormous task of taking back those lands that the Moors had captured.

The first mention of Santiago was in a poem or song written around 783, but little is known about it. The name itself is a hint. Saint James in Vulgar Latin is, Sanctus Iacobus, which, when corrupted by the local Galician dialect Comes out as Santiago. St. James was beheaded in Jerusalem the year 42 on the orders of Herod, and the legend tells that his body was transported from the Holy Land to Galicia in a miraculous ship made of stone. Most historians consider this to have been a local home-grown legend.

It was during the reign of King Mauregato, around 820, that the legend gained momentum. In a hermitage called Peleo in the forest of Libradón, a group of devotees saw miraculous lights in the sky which seemed to fall to earth over a hillock in nearby woods. When the abbot of the hermitage reported this to his bishop, Iria Flavia, the bishop told his superior, Teodomira, who came with an entourage of clerics to witness the events for himself. Over a number of nights, they all watched the stellar display. They cleared the forest over the hillock and began excavating and soon found a stone sepulchre containing three bodies. Teodomira immediately rushed away to tell King Alfonso II about the miracle that he had seen and the bodies that he had found.

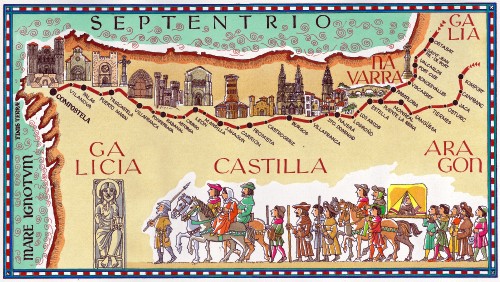

Alfonso was a shrewd king, and he saw the potential for a god given icon that his armies could unite under and fight for. He ordered the bishop to build a small church next to the tomb and use this as his seat of office. It was to be called Compostella, from the Vulgar Latin for burial ground, compostia tella, though there is another theory that the name is derived from campus stellae, “field of the star” but this is an unlikely corruption from Latin to medieval Galician. Whatever the name, it attracted the devoted in their droves, and they made pilgrimages to see the tomb of St. James from all four Christian kingdoms and as far away as Gaul. Coincidentally, Alfonso led several successful campaigns against the Moors after the discovery, which gave weight to the idea that St. James was aiding the Christians.

This is where the truth becomes entangled with myth. Alfonso died in 842 and his successor, Ramiros I, continued the fight against the Moors. According to the legend, Emir Abd al-Rahman II demanded a jizya (a tribute) of 100 virgins, and Ramiros refused to comply. This resulted in the two armies supposedly meeting at Clavijo, where the Christians were outnumbered, but fought valiantly. Before the battle began, Ramiros prayed for victory, promising to give a part of the booty from the battle to the hermitage of Santiago, along with the first fruits of the harvest each year.

St. James Matamoros, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. St. James Matamoros, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

In truth, neither Christian nor Moorish records contain any mention of the battle. The legend was first written down about 300 years after the supposed event. Another embellishment that was added to the fictitious battle at an unknown date was that at the peak of the battle, when defeat seemed imminent, some of the soldiers reported seeing a vision of St. James on a white horse brandishing a raised sword leading them to victory. The year and date of the conflict is different depending on which account you read, and the history of the cult of Saint James is rich in such errors. But it doesn’t matter if it was true or not; the Christians had an icon to follow. The reconquesta continued, but what had been a war of conquest for gain through looting and slavery had become a religious war.

This was not lost on the leaders of the Muslim caliphate in Córdoba. The Shining City was nearly complete, but its penultimate patron, Emir Al-Hakam II, died in 976 and Hisham II became the ruler of al-Andalus. Hisham was a child when he took over a civilisation that was at its peak, and his regent, al-Mansur, who was caliph in all but name, took control. After around 200 years of nearly constant incursions the caliphate from Asturius, al-Mansur decided to take the battle to the Christians. This was not altogether a religious or ideological assault, though he knew as well as the Christians did that the symbolism of a strike deep into Christian lands would bolster his support.

The cost of building Madina al-Zahira, and the bribes in land and gold that he had to give in order to maintain his position as caliph, plus the rising cost of the army that he needed to defend his northern borders required that he raise some money from somewhere, and the growing prosperity of the Catholic Church and the population of the four northern Christian kingdoms were a possible source.

Over the next twenty years, he made around 56 assaults during 9 campaigns on the kingdoms, primarily to deter and weaken the Asturian king, but also to return with as much booty as his troops could carry. In modern day values, they were little more than well organised bank raids.

One of them was on the church of Santiago de Compostella, which had grown over the centuries to be a rich area by virtue of the peregrinos, who had brought what was in reality medieval tourism into the area from Northern Iberia and France. The caliph’s troops would never have found the church had it not been for their hired Christian mercenaries who led him to the town. According to history, the caliph rode his horse into the church and allowed it to drink holy water from the font. The captive Christians of Santiago could only watch in horror as he ordered the church burned to the ground.

Hisham’s troops found little of real value, but the church had expensive cast bells in the belfry. They were removed and carried the 860km back to Córdoba, where they were melted down and cast into lamps to be hung in the Great Mosque. Two and a half centuries later, in 1236, the Castilian King, Ferdinand the Third ("The Saint") reconquered Córdoba. His first action was to avenge the humiliation caused by Al-Mansur. He had the lamps carried back to the shrine of Saint James, where they were melted down again to make a new set of bells.

The not so golden age of al-Andalus was coming to a close, and the turn of the century would see the beginning of a thousand years of religious intolerance and warfare. It was never really the peaceful Camelot that the wistful dream about, but it was a good try. By the end of the first century, Christian troops were blessed and said mass before going into battle to slaughter and loot. Popes, Bishops and even one of the disciples of Jesus would lead armies and carry a sword.

As a final irony, when the conquistadores invaded the Americas, they carried banners and icons of St. James Matamoros to rival the indigenous gods and to protect and sanctify the Spanish troops as they robbed the entire continent of its gold and enslaved or murdered the population.

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (6)

2

Like

Published at 6:00 AM Comments (6)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|