When the lion king roared

Saturday, October 31, 2020

The Castilian army retreated north from the Battle of Algeciras with its tail between its legs. The nobles were demoralised and angry. When he realised that his sons were angered by his wish to have his grandson take the throne, King Alfonso made the huge mistake of going behind their backs and petitioning the pope to ratify his decision. His sons were furious.

The family that King Alfonso X once had was in tatters. Queen Violante took their grandsons away to her brother’s kingdom of Aragon, and Sancho was rallying the disaffected nobles around him. His younger brother, John, had split the vote, and was petitioning another group of nobles to follow him and had allied himself with Lope Díaz III de Haro, one of the powerful disgruntled nobles critical of King Alfonso’s policies. The church had also suffered from Alfonso’s taxes and by 1282 Sancho and his mother, Violante, had obtained the support of the clergy and enough of the noble families to make his move.

King Sancho King Sancho

He travelled to Córdoba on the pretext of discussing the treaties with Emir Muhammad II, but in truth, he arranged a deal whereby the Emir of Granada would leave him alone whilst he fought his father for the crown. With his rear secured, Sancho began to gather his strength for the civil war to come.

Desperate and destitute, King Alfonso sent a message to his arch-enemy, Abu Yusef, offering land and booty if he would help him regain his crown by joining forces and attacking his son’s base in Cordoba. Not surprisingly, Abu agreed. An invitation to invade a demoralised and divided Castile was too much to resist. The two armies met at Sahara de los Atunes and marched inland, and King Alfonso sent emissaries to Sancho offering surrender terms. Abu, fearing raids on the Magreb by the Nazrid emir, took the port of Málaga as a preamble to the battles to come, thus securing his rear.

For a while, many of the nobles supporting Sancho wavered. They had backed a renegade, and were trapped between a hostile coalition of Marinids and Christians and the Caliphate of Granada; any one might renege on all deals if the war looked promising for them. The coalition lasted weeks before the two armies were at odds with each other. Christians who had hated and fought Moors for centuries were marching alongside them, and worse, Abu Yusef was in command of them all.

By mutual consent, the two armies separated at Córdoba, and the Christians attacked alone. The battle resulted in the beheading of the mayor of Córdoba and the killing of the mayor of Seville, who was fighting for the king. Meanwhile, Sancho was in Salamanca and as defiant as ever. The whole campaign had been a waste of money and time. Both armies stood down and acknowledged an expensive stalemate.

Abu led his army back to Morocco, but by allying himself with the Moors, Alfonso had alienated himself from much of Christendom. He still had some followers who preferred having his grandson as king, and he retreated to Seville which had always been loyal to him. He lived there in the Alcazar for the remainder of his life. By 1283, the three factions were warily watching each other and waiting for Alfonso to die.

Almost blind, with a cancer in his left eye which had forced the eyeball out its socket, his legs swollen and numb with dropsy, Alfonso was still a king in his own castle, and though he knew he could not expect to live much longer, he spent his time playing board games and involving himself in new works of culture. He sent messages to both his sons promising gifts of land and title, but to no avail, Sancho wanted the crown, and nothing else would suffice. In a final act of desperation he asked the Bishop of Cádiz and the Archbishop of Seville, his only allies in the church, to petition the pope to have Sancho excommunicated, thus preventing him becoming king. The pope duly gave the old king what he desired, a papal gift that also rendered Sancho’s children illegitimate and therefore also ineligible for the crown.

This is where Sancho showed his true mettle. He cared nothing for the church, and when his father died in 1284, he was crowned King of Castile and León in Toledo by his followers. He immediately began a purge of his enemies. He cornered Lope Díaz III de Haro, the lord of Biscay, near Badajoz and had him executed. Other nobles had allied with Lope, and Sancho ordered the execution of them and 4,000 of their followers at Talavera. One of the supporters of Ferdinand de la Cerda hid in the poor town of Ávila, which was a Cerda stronghold. They would not give him up, so Sancho ordered the whole town murdered. Sancho’s brother, John, he threw into prison for being a co-conspirator with Lope. With many of his enemies dead, Sancho now had good chance of keeping the crown.

Whilst Castile had been in turmoil, Abu Yusef Yusuf had to spend much of 1284 putting down a Maqil rebellion in the Draa valley. In Granada, the Banu Ashqilula, under a renewed Nasrid assault, had again appealed to the Marinids for help. Abu had been watching the rise of Sancho, and he preferred King Alfonso’s grandson as king; he knew Sancho was going to be a formidable enemy . Sensing an opportunity to capitalise on Granada and Castile’s weakness, in 1285 he mounted another expedition across the straits. As before, he landed his army at Tarifa and swept north to devastate a broad area from Medina Sidonia to Carmona, Ecija and Seville. Nervous at Seville's disposition (a Cerda party stronghold), Sancho IV assembled his army there, and dispatched the Castilian fleet, some hundred ships under his Genoese admiral Benedetto Zaccaria, to blockade the mouth of the Guadalquivir, and prevent the Marinid navy from assaulting Seville upriver. Abu was close to laying siege to Jerez by August 1285, but Sancho marched the Castilian army south to stop him. Abu decided not to engage Sancho at Jerez. He withdrew his army and haughtily asked to open negotiations with the king, thinking that the Christians were bankrupt and could not sustain another war. Abu had seriously underestimated Sancho, who spurned his offer to negotiate and drove him back to Algeciras. Legend has it that Sancho´s return message offered Abu a carrot, and if he did not accept the carrot, he would show him the stick.

That October in 1285, Sancho IV of Castile secured a five-year truce and treaty with the Marinid emir Abu Yusuf. In return Abu promised not to intervene in Castile for the Cerda party, and the Marinids received equal assurance that there would be no more Castilian attacks on Muslim territories in Spain. To seal the deal, Sancho IV agreed to hand over to the Marinids the collection of Arabic books that had been seized from Andalusian libraries by Church authorities during the Reconquista, in return for Marinid payment of 2,500,000 maravadís cash compensation for the Castilian property taken and damaged by the Moroccan armies.

In March, 1286, Abu Yusuf also began negotiating a final settlement with the Granadan ruler Muhammad II. The Nazrids agreed to recognize Marinid possession of Tarifa, Algeciras, Ronda and Guadix, in return for which the Marinids agreed to surrender all other possessions in Iberia. The remnants of the Banu Ashqilula family would be exiled to Morocco, and the Marinids would guarantee they would cease all intrigues against the Nasrid rulers.

Th Moroccan emir was in the middle of these negotiations, when he fell ill and died on 21 March 1286 in Algeciras. Abu Yusuf's remains were translated to the Marinid necropolis at Chellah, where he had built a tomb. The new emir, Abu Yaqub Yusuf had no sooner taken his father’s title than he suffered and attempted coup from his own son, backed by the ever persistent rulers of Tlemcen. He survived, but he would be locked in a relentless war with his neighbours in the Maghreb until the end of his life.

Abu Yaqub Yusuf entered the negotiations in place of his father, but his stance was more along the lines of forming an alliance with the Nasrid emir to fight the Christian kings. Muhammad II sent envoys to Sancho with a plea to join the alliance and prevent another war. Sancho’s reply was that he would make an agreement with Muhammad, but that Abu’s son was untrustworthy and was still planning on making war. Sancho was right. In the harbour at Tangier, Abu Yaqub was gathering invasion barges from all over the Mediterranean. Sancho knew that he would use Algeciras or Tarifa to land his army, and so his arrangement with the Granadan emir was to unite forces and take the two ports from the Marinids.

The statue of Sancho IV in Tarifa. The statue of Sancho IV in Tarifa.

By 1292 Sancho had Tarifa and Algeciras under siege. Abu Yaqub was almost ready to invade. He had 12,000 men camped on the beach, and he brought the invasion barges out of the harbour and moored them ready for the troops to embark. Muhammad had bolstered Sancho’s navy with his ships, and they patrolled the straits together. Early in the morning on the day that Abu’s fleet was to sail, the Castilian navy appeared on the horizon, and Abu was helpless to prevent them boarding and burning his invasion barges. The troops on the beach could only scream abuse at the Christians as they departed. Within weeks, the port of Tarifa fell to Sancho’s army, but Algeciras remained a Marinid held fortress. There was one more Marinid invasion to come, and it would produce one of Spain´s greatest heroes.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (4)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (4)

A wealth of knowledge and a brace of betrayals

Saturday, October 24, 2020

When Abu Yusef Yaqub returned victorious to Fez In March, 1276 he began the building of El-Medinat el-Beida (White City), on the other side of the river from the old Idrisid city of Fez, which is now known as Fez el-Bali (Fez the Old). The new city was to be a showpiece of Islamic culture, like the Shining City of Córdoba had been two hundred years before. The madrasa of al-Karouine was becoming renowned as a centre of learning, and Abu wanted to elevate his caliphate to the same level of culture that the Umayyad caliphs had achieved. He didn’t know it then, but he was up against some stiff opposition from Toledo.

When King Alfonso’s father had driven the Almohads out of Iberia he discovered that they had left their libraries intact. During the rapid rise and spread of Islam, the different cultures they replaced were absorbed, not destroyed. Thousands of years of written history, science, religion astronomy and law were here in these parchment books and scrolls. But they were nearly all written in Arabic or Hebrew. From the beginning of his reign, King Alfonso instigated and personally supervised the translation of all the books in the libraries, employing Jewish, Christian and Muslim teams of translators. This group of scholars formed his royal scriptorium, known as the Escuela de Traductores de Toledo (Toledo School of Translators). By translating into Castilian, Alfonso promoted Castilian to a language of learning both in science and literature and established the foundations of the new Spanish language.

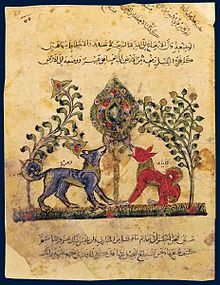

Kalila wa-Dimna Kalila wa-Dimna

One of the first books to be translated was a Castilian version of the animal fable Kalila wa-Dimna, a book of stories and sayings meant to instruct the monarch in proper and effective governance and was similar to Aesop’s fables. His next book, the Fuero Real was without doubt all Alfonso’s work and was a basis for the laws of his kingdoms and a textbook for the judiciary to follow in their day-to-day decisions.

In 1273 he created the Mesta, which was an association for sheep farmers. At first sight this seems to be a trivial innovation, but it came at a time when the traditional dominance of the English woollen trade had slumped. By coordinating the efforts of Castilian pastors, who until then were nomadic, Alfonso rejuvenated exports of Castilian wool to all Europe, and this vital clothing commodity became his kingdom’s biggest export, earning it the name of “white gold.”

With so many different languages, religions and legal systems deal with in his realm Alfonso tried to reform them under one legal code and one language.

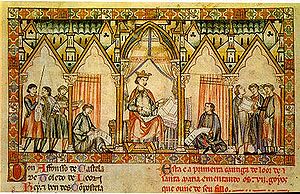

The Siete Partidas The Siete Partidas

His father had attempted to do the same and had adopted the fueros of the Vizigoths, but they were only accepted in localised areas. Alfonso set up a commission of jurists (or members of the chancellery) to write the Siete Partidas a legal system in Castilian. More a universal encyclopedia for the governing of such different cultures, it incorporated philosophical and moral issues taken from Judean, Christian and Islamic teachings. On a more practical level, it guided the behaviour of his knights in carrying out their duties. The Siete partidas was never accepted by his nobles or his son who followed him as king, and it was only when his grandson, Alfonso XI, revived the laws nearly a hundred years later that they were widely adopted. One outcome that Alfonso could never have imagined was that his laws would be used to govern Spain’s post Columbus South American possessions, and are still a large part of their present day legislation. As a final recognition of Alfonso’s wisdom, his portrait hangs in the US House of Representatives chamber, along with 22 other lawmakers who are honoured there.

Perhaps his greatest contribution was to astronomy. Ptolomy’s Almagest, (The Greatest), which was written around 150 CE by the Greek astronomer, Claudius Ptolemy, but was taken from an earlier work from around 350 BCE by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who was a profound thinker on just about every subject then known. Three hundred years after Ptolemy, the Persian astronomer Al-Sufi corrected many of Ptolemy’s original observations. To this was added the corrections of al-Andaluz astronomer al-Zarqali, and finally, what lay before King Alfonso’s translators was the sum total of all the world’s knowledge of astronomy in one place, and written in Castilian.

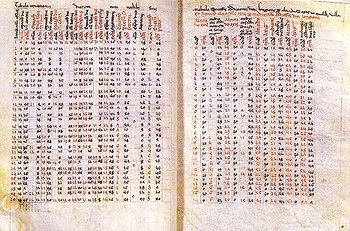

The Alfonsine tables The Alfonsine tables

That would be enough of an achievement for most scholars, but King Alfonso ordered his astronomers to create another set of tables from their own observations that accurately predicted the motion of the visible planets against the fixed stars. These he added to the Almagest as the Alfonsine tables. Just over two hundred years later, Nicolaus Copernicus had a copy of the Alfonsine tables with him when he was studying in Kraków, and the accurate measurements helped him form his own heliocentric theory, which places the sun in the centre of the solar system. Like Copernicus, Alfonso is honoured with the naming of a crater on the moon after him.

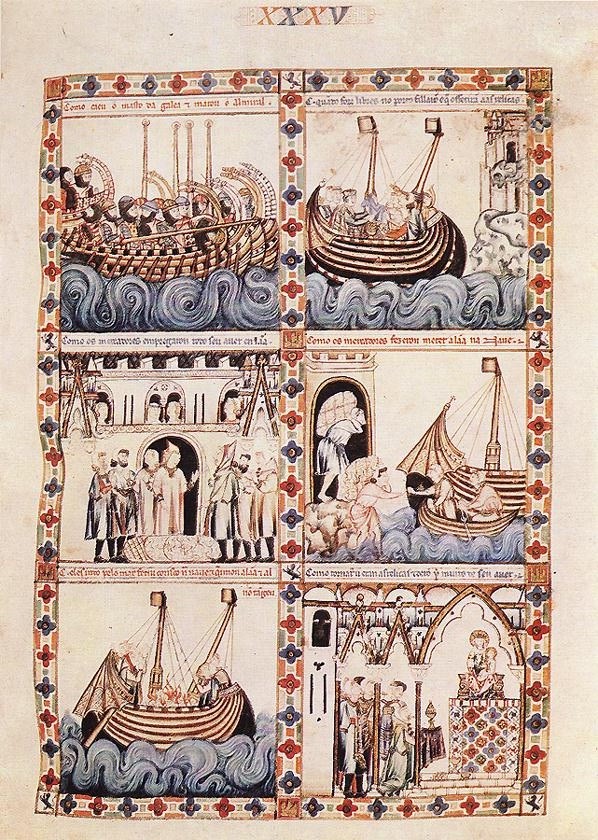

Miniatures from The Cantigas de Santa Maria Miniatures from The Cantigas de Santa Maria

Alfonso also dabbled in music and games. The Cantigas de Santa Maria, 420 poems with musical notation, written in medieval Galician, is often attributed to King Alfonso. It is one of the largest collections of monophonic (solo) songs from the Middle Ages, and is characterized by the mention of the Virgin Mary in every song, with every tenth song being a hymn. Only four manuscripts survive; two at El Escorial, one at Madrid's National Library, and one in Florence, Italy. The E codex from El Escorial is illuminated with coloured miniatures showing pairs of musicians playing a wide variety of instruments.

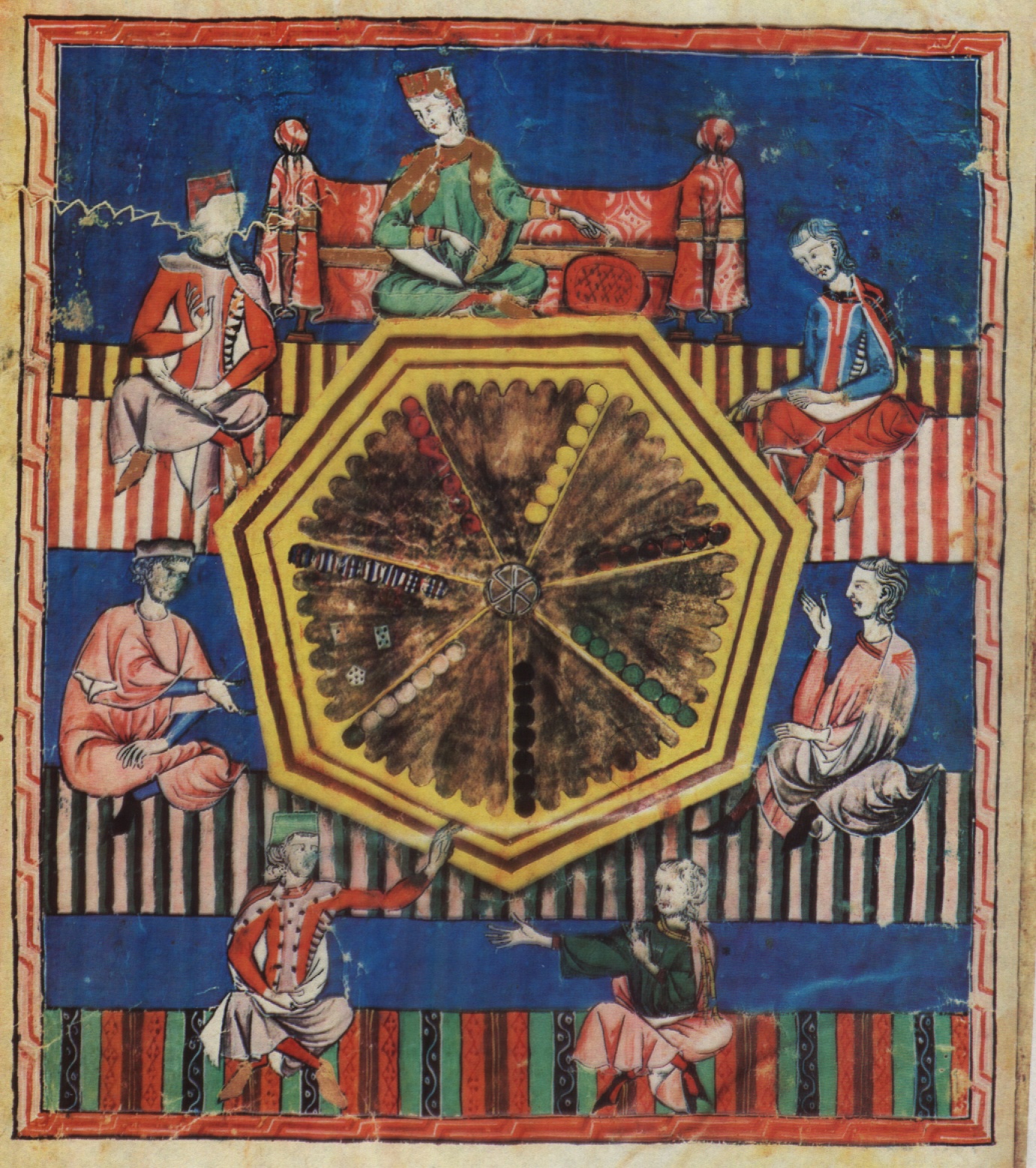

Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas

King Alfonso’s Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas or Book of chess, dice and tables, consists of ninety-seven leaves of parchment, many with colour illustrations, and contains 150 miniatures. The text is a treatise that addresses the playing of three games: a game of skill, or chess; a game of chance, or dice; and a third game, backgammon.

Abu Yusef Yacub had none of Alfonso’s qualities or abilities, but he had ambition, an army, and he was ruthless. He had tested the strength of Castile and the Caliphate of Granada, and knew their weaknesses. Before leaving Iberia, Abu had signed a treaty with King Alfonso X, in which he promised not to attack Castile for two years. But he had left the broad Guadalquivir valley desolated. All the Christian settlers who had filled the void left by the Moors were now in the slave markets of Salé in Morocco, and their cattle distributed as booty to his al-qa’ids(military commanders). Abu knew how close he had come to defeating the Christians, and as soon as he returned to Africa, he began planning his second invasion, hoping that the Christians would not have time to repopulate the land that he had ravaged. Abu had only stopped because he had so decimated the land that he could not feed his army. In the next invasion, he would try to remedy that error.

In Castile, King Alfonso began to pick up the pieces of his kingdom. He had lost his eldest son, Ferdinand, but his younger brother, Sancho, had shown extraordinary courage and determination in leading his army in his absence; a character value that he was about to hugely underestimate. The death of Ferdinand had left two fatherless grandsons, Alfonso and Ferdinand de la Cerda, and King Alfonso unwisely decided to bypass his own two sons, Sancho and John, and nominate Alfonso as heir to the throne of Castile. At a stroke, he alienated his own sons, his wife and half of the nobles in his kingdom. Sancho claimed the right, of proximity of blood and agnatic seniority, which was laid down in the old Castilian laws, but Alfonso would not hear of it, and stubbornly refused to budge. His now estranged wife fled to Aragon, taking her grandsons with her for their own safety. Chroniclers have debated whether this family feud had disturbed the mind of King Alfonso at a critical time, because some of the decisions that he made over the next few years were nothing short of catastrophic for Castile.

Meanwhile, the treaty with Abu had expired, and in In August 1277, the emir crossed the straits again with a Moroccan army. As before, he swept north ravaging the lands south of the Guadalquivir. Abu’s son drove up the west coast and took the ports of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Puerto Santa Maria and Rota, having first laid siege to Seville. He returned to Seville, but could not break the city, and after a month gave up. He had so devastated the land that his army was running out of food. He ordered his men to return to Algeciras with their slaves and booty and a month later, after re-provisioning, he swept north again to take Jerez before swinging east to join his father to take Córdoba. By the end of august, Emir Abu Yusef held the whole of west al-Andaluz in his fist. This was when he revealed his master plan. Instead of supporting Muhammad, the emir of Granada, he betrayed him, and formed an alliance with the Banu Ashqilula, his enemies.

Incandescent with rage, Muhammad is said to have paced the corridors of his palace alternately screaming abuse, or wailing his misfortune. Abu had been offered the port of Málaga as a bribe, a prize that he coveted. When he recovered, Muhammad asked for the support of Alfonso X and the Abdalwadid ruler Yaghmorassan of Tlemcen to punish the Marinids. It fell to Sancho again to lead Alfonso’s army against the Marinids.

In early 1279, while the Abdalwadids launched a diversionary raid on Morocco, and the Castilians dispatched a fleet to blockade the straits and stop Abu ferrying food and replacements for his army. Muhammad II led a Granadan army upon Málaga, which soon fell in a negotiated settlement. In a new treaty, Marinid emir Abu Yacub agreed to surrender his claims on Málaga and withdraw his protection of the Ashqilula, in return for which Muhammad II handed over Almunecar and Salobrena to the Marinids.

No sooner was this deal done, that the attention of the Muslim parties turned towards Marinid controlled Algeciras, which Alfonso X had decided to take for himself. Sancho had driven Abu south and laid siege to Algeciras. The ships of the order Santa Maria de España, specialists in naval warfare, dropped anchor off Isla Verde to stop Abu reliving it from the seaward side.

With another flip of loyalties, Muhammad II lent his own ships to join the Marinid fleet under the command of the Abu Yusuf's son, Abu Yaqub. The Moors were anxious not to let such an important port fall into Christian hands. The siege of Algeciras dragged on for months and took more out of the attackers than the defenders, who had bountiful supplies taken from the Guadalquivir valley. Alfonso’s navy soon ran out of supplies, and scurvy broke out among the crews, who abandoned their ships and came ashore. When Abu discovered that the fleet was abandoned, he sent his ships across the straits, captured the Christian navy, and lifted the siege at the Battle of Algeciras on 21 July 1279.

Sancho was still denied the crown of Castile by his father, and after displaying his courage in battle he had gained the loyalty of many of the nobles of Castile. Sancho was about to give his father a brutal lesson in kingliness.

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (6)

The maybe not so wise king.

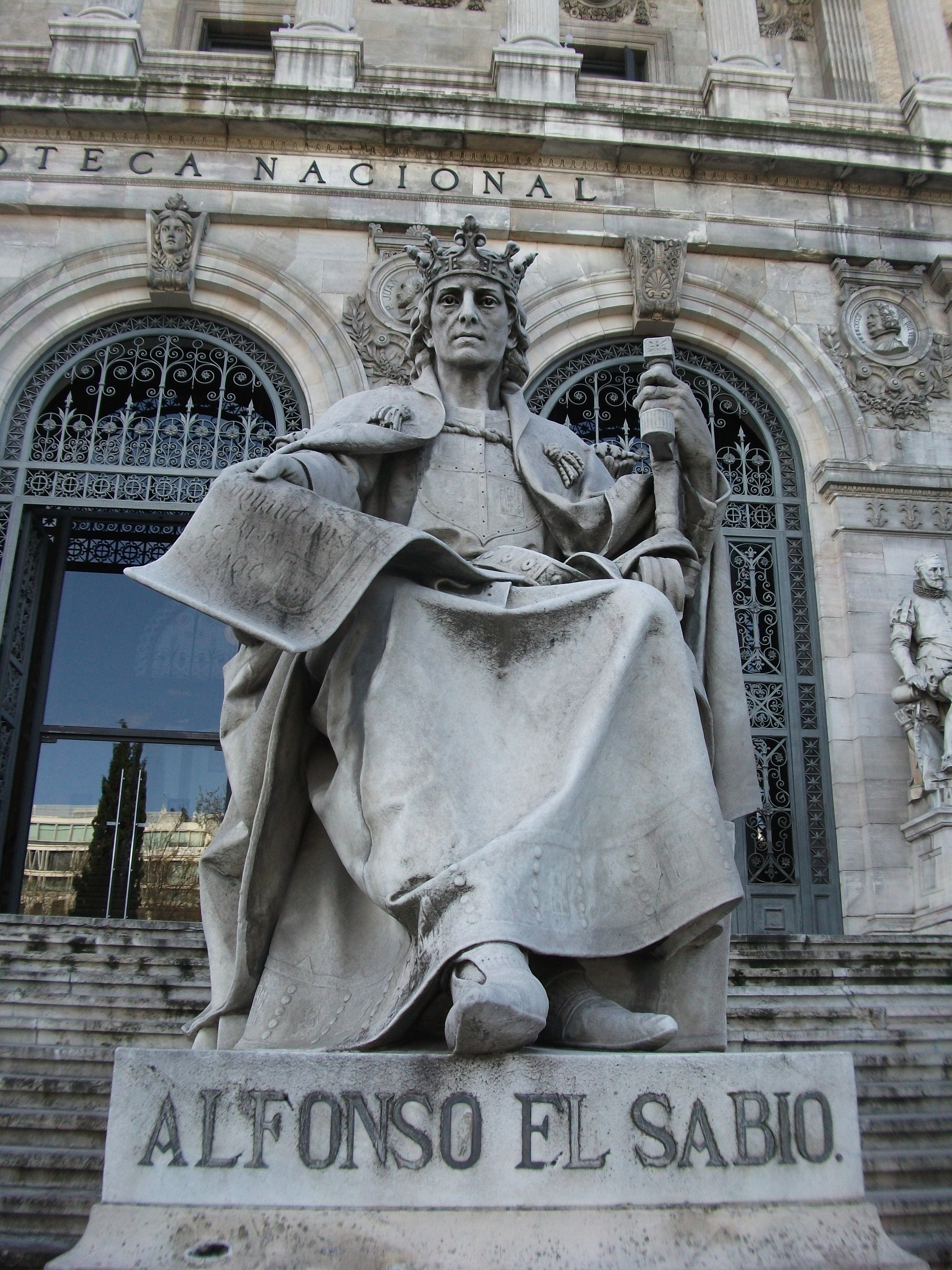

Saturday, October 17, 2020

After the capture of so much land from the Moors, the Kingdom of Castile struggled with the repopulation, control and financing of its much enlarged domain. This task fell on the shoulders of King Ferdinand III’s son, Alfonso. King Alfonso X of Castile and León was called “El Sabio” (the wise), but there are two sides to King Alfonso. If you measure his reign in battles won, then he would be a failure. If you measure him as a diplomat, who ruled a peaceful country, then he would fail again. But if you measure him as a visionary lawmaker, writer and scholar, who fostered enlightenment in the dark ages, then he earned his title of El Sabio.

The next round of wars between the Catholic Kings and the Marinid and Granadan caliphates would involve Alfonso X and his sons, Sancho and John, but it would not go well for either side. For the next 200 years, little land would be gained, but hundreds of thousands of lives lost in wars of attrition as the moors tried to recover lost territory

At first, Alfonso was only heir to the crown of Castile, but his father united the kingdoms of Castile and León when he was nine, and he became the prince of two kingdoms. His training as a soldier began from the age of sixteen under the guidance of his father, and they fought together in several successful campaigns during which they took Murcia, Alicante and Cádiz from the Moors.

It was while he was serving in the army with his father, that young Alfonso was struck with the code of chivalry and mutual respect between knights. He soldiered with Perez de Castron, a friend of his father, and what the old knight taught him, and he subsequently saw for himself in battle, left a lasting impression on the young prince. He wrote later that during a battle to take Jerez, he had a vision of St. James mounted on a white horse holding a white banner in the sky above Castilian troops. This revelation appears to have formed his later opinions on law and the conduct of knights.

Prince Alfonso was not so pious when it came to the ladies. When Theobald I of Navarre was crowned, Alfonso’s father tried to arrange a marriage with Theobald’s daughter, but Alfonso had already fallen for Mayor Guillén de Guzmán, who bore him a daughter, Beatrice. The couple married in 1240, but they were forced to annul the marriage and Beatrice was declared illegitimate. During his lifetime he also fathered two other illegitimate children.

Nine years later, Alfonso, now twenty-eight, was married to thirteen-year-old years-old Violante of Aragon. For the first few years of the marriage, poor Violante was too young to be a wife, but after puberty, several years passed without any sign of pregnancy. Alfonso considered writing to the Pope asking to annul the marriage, but during one of the campaigns against the Moors in Alicante, legend says that the king and queen spent a few nights resting in a small farm in the countryside, and it was during their stay, she became pregnant with their first son, Ferdinand. A grateful Alfonso called the farm the "the plain of good sleep" or "pla de bon repos." Now a suburb of Alicante, it is still known by this name today.

In 1252, upon his father’s death, he was crowned King of Castile and León and his first act as king was to invade Portugal, forcing the greedy and avaricious King Afonso to surrender his kingdom. Clever Alfonso struck a deal with the Portuguese king, making him divorce his own wife and marry Alfonso’s illegitimate daughter Beatrice - or lose his kingdom. Poor Afonso had no option but to comply. This meant that Alfonso’s daughter would be queen of Portugal, and any children would inherit the crown of Portugal, but be allied to Castile and León.

But ambitious Alfonso came unstuck when he tried to lay claim to the biggest prize of all.

His mother was a daughter of Emperor Philip of Swabia, which meant that he was eligible to be King of the Holy Roman Empire. However, to be chosen, Alfonso needed to convince the prince-electors of the Vatican that he was worthy of the title. This usually involved lengthy negotiations and large-scale bribery. Alfonso had a rival for the title, Richard of Cornwall, and the prince-electors had a field-day playing the two off against each other. In the end, Richard of Cornwall was selected because Alfonso had supported people that Pope Alexander IV didn’t like. Richard went to Germany and was crowned in 1257 at Aachen, and Alfonso had to face the music at home.

To raise money to fund his claim for the throne of The Holy Roman Empire, Alfonso had debased the coinage of Castile and then endeavoured to prevent a rise in prices by an arbitrary tariff. The little trade that his dominions had established was ruined, and the burghers and peasants were deeply offended The mudejar uprising in 1264 was a rebellion by the Moors living in Castile who were unhappy with the unfair laws and increased poverty caused by King Alfonso’s taxation, but they were in part stirred up by the Granadan emir. The end result was the expulsion en-masse of the Moors from Castile.

The Marinids began to figure in King Alfonso's fortunes when they crossed the straits to occupy the old Almohad territories, But It was when Abu Yusuf Yaqub formed an alliance with the Caliphate of Granada that King Alfonso decided to take the war to Morocco, and sent a fleet of ships carrying troops to invade Salé in September 1260. The port was occupied for a short while, but Alfonso’s men were eventually repulsed. He tried to invade again in 1267 with a larger force, but his troops were once again driven out. Abu Yusuf decided that in order to protect his interests in Iberia, and to stop invasions on his own shores, he needed to take key ports on the southern coast of Iberia. Whoever controlled the straits would have the upper hand in fighting a war.

Abu Yusuf entered Marrakech in September 1269, putting a final end to Almohad rule. The Marinids were now masters of Morocco, and Abu Yusuf took up the title of 'Prince of the Muslims' (amir el-moslimin), the old title used by the Almoravid rulers in the 11th-12th centuries. However, the Marinids had some difficulty getting their authority recognized by the southerly Ma'qil Arabs of the Draa valley and Sijilmassa. The Draa valley Arabs submitted only after a campaign in 1271 and Sijilmassa only in 1274. The northerly city ports of Ceuta and Tangiers also refrained from acknowledging Marinid suzerainty until 1273.

Whilst King Alfonso had spent ten years and tens of thousands of maravadís in bribes chasing the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, he had also been foolishly meddling in the affairs of the Granadan Caliphate. With the encouragement of King Alfonso, the Banu Ashqilula family, rulers in Malaga, Guadix and Comares, had risen up against the young emir. To make matters worse, he had raised the tribute that the emir was forced to pay. Emir Muhammad II el Fagih had objected, but some of Alfonso’s disgruntled nobles had been making their own pacts with the emir, who was instigating his own rebellion against Alfonso. His nobles, whom he tried to cow by sporadic acts of violence, rebelled against him in 1272.

Finally, Muhammad sent the king a letter asking him to stop stirring up trouble in his caliphate along with a present of 300,000 maravadís and a promise not to give aid to his rebellious nobles. Instead, Alfonso took the money and not only continued fomenting insurrection with the Banu Ashqilula in al-Andaluz, but started encouraging the Abdalwadid ruler, Yaghmorassan of Tlemcen to rise up against Abu Yusef in the Mashriq.

Whilst Alfonso's meddling was coming to a head, Richard of Cornwall died, and the king dropped everything to pursue the crown of Christendom once again. This time, he intended to travel to Italy make his case to the pope in person, but the pope thwarted his ambitions and met him in Provence. After a long, stern bout of negotiations, he obtained Alfonso's word that he would abandon all attempts to claim the title of King of the Romans. It was during these negotiations, whilst his oldest son, crown prince Ferdinand de la Cerda was acting as prince regent of Castile, that the future of Iberian Christendom faced the greatest threat since the initial Islamic invasion.

Realising by now that he had been lied to, the Nasrid ruler, Muhammad II of Granada, appealed to the Marinid emir Abu Yusuf Yaqub for assistance, but the Marinid emir was already engaged against Tlemcen and couldn’t help. The civil war in his caliphate worsened, and Muhammad renewed his request to the Marinids for assistance, offering them the Iberian towns of Tarifa, Algeciras and Ronda as payment. This very tempting offer arrived just as Abu Yusef crushed the uprising in Tlemcen.

With his enemies now subdued, Abu Yusuf Yaqub took up the Nasrid request, and in April 1275, crossed the straits to land a 50,000 strong Moroccan army in Spain. The Marinids quickly took control of Tarifa and Algeciras, and confirmed their pact with Muhammad II. The Banu Ashqilula were now hugely outnumbered and promptly capitulated, and the Emir of Granada immediately ordered the commanders of his 80,000 troops to invade Castile and take back Córdoba. Alfonso´s son was now facing invasion by a vastly superior force on a 300 mile front, and was totally unprepared for war.

Abu Yusef and his son drove their army north, destroying everything in their path and enslaving the newly-settled Christian farmers. When Prince Ferdinand received news of the invasion he called the nobles of all the kingdoms to arms and managed to raise enough men in time to meet the invading Marinids in the west, whilst his younger brother, Sancho, led another army against the Nasrid forces around Córdoba. But on the march south, before battle could be met, Prince Ferdinand fell sick and died near Villa Real.

Nuño González de Lara "el Bueno", the head of the House of Lara, took control of the army and attempted to halt the Marinid advance in a battle near the town of Écija in September. The Christians were routed, and Nuño was captured or killed. Abu ordered his head cut off and sent to Muhammad as a trophy. The Christians, after regrouping and being reinforced, mounted another attack a month later led by Archbishop Sancho of Toledo, which met a similar defeat at the Battle of Martos. The Archbishop was killed, and it was only the efforts of King Alfonso’s son, Sancho, who rode from the defence Córdoba to take the lead at the head of his father’s army in the west that saved the day.

By now, King Alfonso had returned from France, and he immediately sent a plea to Abu to end the war and open negotiations for peace. His primary mission achieved with the aid to the Nasrid caliphate, and thousands of slaves and cattle as a prize, Abu agreed.

King Alfonso had made some mistakes with his rule, but his biggest mistake was yet to come, and it would tear his kingdom apart. But out of it would come two of Spain’s greatest heroes, and one of its greatest villains.

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

The rise of the Marinids

Saturday, October 10, 2020

The western Sanhaja tribes had been converted to Sunni Islam sometime during the 9th century. They were subsequently united in the 10th century, and with the zeal of new converts, launched several campaigns against the pagan peoples of sub-Saharan Africa. Tribal leaders and alliances came and went, but the vital trans-Saharan trade routes were, in part, supported the Zenata Maghrawa tribe from around Sijilmassa. The Zeneta tribe differentiated itself from other tribes by adopting the name their ancestor, Marin ibn Wartajan al-Zenati, and were originally a nomad tribe who moved seasonally between the Figuig oasis to the Moulouya River basin. With the arrival of the Arabs in the 11th and 12th centuries, the Marinids, as they now called themselves, moved to the north-west of present-day Algeria, before migrating en-masse into Morocco at the beginning of the 13th century.

Saharan camel trade routes and the gold mines of sub-Saharan Africa (in gold)

After arriving in Morocco, the Marinids initially submitted to the Almohad dynasty and even assisted the Amohads at the battle of Alarcos in 1195. Their relationship with the Almohads became strained, and starting in 1215, there were regular outbreaks of fighting between the two tribes. In 1217 they tried to occupy the eastern part of present-day Morocco. They were expelled and pulled back to settle in the eastern Rif mountains, where they remained for nearly 30 years. Meanwhile, the Almohad state suffered huge setbacks, losing land to the Christians in Spain, whilst the Hafsid tribe of Ifriqia broke away in 1229, followed by the Zayyanids of Tlemcen in 1235. Between 1244 and 1248 the Marinids were able to take Taza, Rabat, Salé, Meknes and Fez from the weakened Almohads. Once the Marinids took control of Fes under the leadership of Abu Yusuf Yaqub, they declared war on the Almohads, and with the aid of Christian mercenaries captured Marrakech in 1269.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Just about the same time that relations between the Marinids and Almohads had deteriorated to open war in the Rif Mountains, (1212) the Almohads lost the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in Iberia, and their leader, Muhammad al-Nasir, returned to Marrakech where he died shortly afterwards. This was the turning point in the Christian reconquest of Iberia.

Immediately after the battle, the much weakened Christians rallied, and King Alfonso took Baeza and then Úbeda, major fortified cities near the battlefield and gateways to the invasion of Andalusia. According to the Latin Chronicle of Kings of Castile, when these two fortresses fell, 60,000 Muslims were killed and 100,000 more were taken into slavery, including women and children. Whilst the Almohads were facing internal conflicts, Alfonso and later kings of Castile and Aragon took advantage of their weakness, and Muslim controlled cities fell like dominoes.

Alfonso VIII's grandson, Ferdinand III of Castile, took Córdoba in 1236, Jaén in 1246, and Seville in 1248. He went on to take Arcos, Medina-Sidonia, Jerez, and Cádiz. Meanwhile, James I of Aragon conquered the Balearic Islands over four years starting in 1228, and Valencia capitulated to him in 1238.

King Ferdinand III was undoubtedly the most successful of the Christian kings, and when he died in 1252 he left a united Castile and León, and his campaigns over 20 years gained more land from the Caliphates than any other. He left some of the captured taifas as Muslim vassal states, which eventually became absorbed into Castile. (Niebla in 1262, Murcia in 1264, Alicante in 1266). Even the powerful Caliphate of Granada was forced to pay tribute to Castile.

He gave parcels of the new lands to his dukes and knights, with the church also receiving a portion of the gains. He added to the University of Salamanca and erected the current Cathedral of Burgos as well as donating to the Benedictine monks and the Cistercians and Cluniacs, who had taken a major role in the Reconquest. In 1252, Ferdinand readied his fleet and army for invasion of the Almohad lands in Africa. But he died in Seville on 30 May 1252 during an outbreak of plague in southern Hispania. Only Ferdinand's death prevented the Castilians from taking the war to the Almohads.

On his deathbed, Ferdinand told his son, Alfonso "you will be rich in land and in many good vassals, more than any other king in Christendom." For the next 200 years, the frontiers would more or less remain static, but the united Christian Iberia that King Alfonso X inherited would be torn apart by civil war and ravaged by the Marinids.

By 1265 the only remaining Muslim governed lands in Iberia were the Nazrid Caliphate of Granada and what was left of the Almohad caliphate.

In Africa, the Marinids led by Abu Yusuf Yaqub, had subdued the last Almohad outpost of Marrakech and he turned his attention on al-Andaluz. He crossed the straits, subdued the isolated Almohad taifas in al-Andaluz, and formed an alliance with the Nazrids to defend and enlarge Muslim controlled parts of Iberia. The fall of so much of Muslim al-andaluz to the Christians, and their subsequent maltreatment, caused a mass Muslim exodus to the caliphates in the south. This added to their strength in numbers, and Abu was fully intent on supplying them with arms and reclaiming their lost lands. But both caliphates had their own problems; Abu Yusuf Yaqub had to deal with constant attacks from the Abdalwadid kingdom of Tlemcen in the Mashriq, and in 1272, the Nasrid ruler Muhammad I faced a challenge from the rival Banu Ashqilula family, who were rulers of Malaga, Guadix and Comares. The reconquest was far from over.

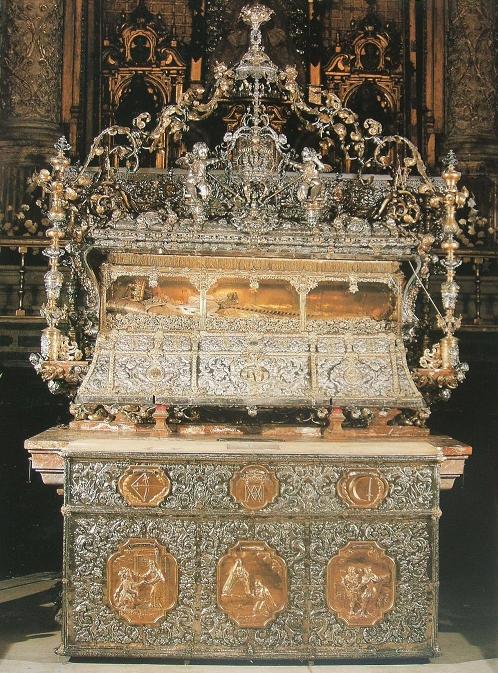

The tomb of Saint Fernando. The tomb of Saint Fernando.

King Ferdinand III was interred in the Cathedral of Seville by his son, King Alfonso X. His tomb is inscribed in four languages: Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, and an early version of Castilian. Today, the uncorrupted body of Saint Fernando can still be seen in a gold and crystal casket. His golden crown still encircles his head as he reclines beneath the statue of the Virgin of the Kings.

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

The hermit who founded an empire

Saturday, October 3, 2020

Ali ibn Yusuf is said to have been a 100 years-old when he died in 1106, and nine years before his death, he had assumed the title of Amir al Muslimin. (Lord of the Muslims) Almoravid power under Yusuf had reached its height, and its empire then included all of Northwest Africa as far eastward as Algiers and more than a thousand kilometres of Atlantic African coastline. They controlled all of Iberia south of the Tagus, and as far eastward as the mouth of the Ebro, including the Balearic Islands.

Yusuf had appointed his brother, Tamim Al Yusuf, as his successor, and it was he who continued the fight against the Christians in al-Andalus. In 1108 he defeated the forces of Castile and León under Alfonso VI at the battle of Uclés just south of the river Tagus. Many of the high nobility of León, including seven counts, died in the fray or were beheaded afterwards, while the heir-apparent, Sancho Alfónsez, was murdered by villagers while trying to flee. The Almoravids again failed to go on and take their biggest prize, the city of Toledo.

Tamin’s son and successor, Ali ibn Yusuf, was occupied with insurrection in Morocco and it was 1119 before he could return to al-Andalus to deal with a Christian uprising in Córdoba as well as renewed attacks on his northern borders with Christendom. He returned in 1121 and as soon as he arrived he realised that he was facing a different level of threat. The French had joined forces with the Aragonese to take Zaragoza, and in 1138 his army were defeated by Alfonso VII of León. A year later, he was again defeated by Alfonso I of Portugal at the battle of Ourique. Ali ibn Yusuf died in 1143 and was succeeded by his son, Tashfin ibn Ali, but in 1146 he was killed in a fall from a precipice during a battle near Oran. Pockets of Almoravid rule continued for another 100 years, but they had effectively been replaced by another Berber tribe led by Ibn Tumart, who had begun his rise to power around 1120 in Morocco.

The Almoravids were a Sanhaja Berber tribe, whilst Ibn Tumart was a member of the Masmuda, a Berber tribal confederation in the Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco. As a young man, Tumart travelled to Iberia to pursue his studies, and thereafter to Baghdad to continue them. It was in Baghdad that Tumart began to follow the theological school of al-Ash'ari and came to develop his own theological creed. His followers would become known as the al-Muwaḥḥidūn (Almohads), meaning those who affirm the unity of God.

How the Almohads came to dislodge the Almoravids is quite an amazing story.

From 1117 onwards Tumart travelled to a number or Ifriqiyan cities. He began preaching that the Almoravid rule was lax and straying from the Qur'an. He led attacks on wine-shops and opposed the Maliki school of jurisprudence. His fiery preaching led the authorities to move him along from town to town. Finally, he set up camp on the outskirts of Mellala, where he received his first disciples; Al-Bashir, and Abd al-Mu'min, who would later become his successor. Tumart led his small band of followers to Fez, where he debated with the Maliki scholars, but he was expelled from the city after he allegedly berated the sister of the emir for not wearing her veil in the street.

In Marrakesh he sought out Emir Ali ibn Yusuf in a mosque and challenged him and his scholars to a doctrinal debate. The emir agreed, but after the debate the scholars decided that Tumart’s views were blasphemous and that he was dangerous. They urged the emir to have him put to death or imprisoned, but the emir wisely decided to simply throw him out of the city.

Tumart went back to his home village of Igiliz in the Sous valley and hid among his own tribe, the Hargha. He became a hermit, and lived in a cave, only coming out to preach his program of puritan reform. His following grew, and in late 1121, he gave a particularly moving sermon explaining that he could not reform the ruling Almoravids by argument alone. He then declared himself as the true Mahdi; a divinely guided judge and lawgiver. He was urged by his followers to move into the High Atlas Mountains among the Masmuda tribes where his support grew, and where he set up the ribat of Tinmel, an impregnable fortress which would be the future headquarters of the Almohad movement.

The mosque at Tinmel The mosque at Tinmel

From this base he dominated the western end of the trans-Sahara trade route and its terminus, Sijilmassa. Despite attempts to dislodge him, the Almorovids could not pin his forces down, and they sought alternative routes for trade. But it was the social structure of the base that made it revolutionary. The core was Ahl ad-dār (House of the Mahdi), composed of Ibn Tumart's family. This was supplemented by two councils: an inner Council of Ten, the Mahdi's privy council, composed of his earliest and closest companions, then the consultative council of fifty, composed of the leading sheikhs of the Masmuda tribes. It had a military hierarchy organised along the same lines, with an administrative branch for tax collection and control of finances. Finally Tumart's closest companion and chief strategist, al-Bashir, took upon himself the role of "political commissar" enforcing doctrinal discipline among the Masmuda tribesmen.

It was 1130 before they felt confident enough to come out of the mountains and make their first sizable foray against the Almoravids. They scattered the column that came out to meet them and chased them all the way to Marrakesh, where they laid siege to the city for forty days. Finally, the Almoravids stormed out and crushed the Almohads in the bloody Battle of al-Buhayra. Thoroughly routed, with huge losses, and half their leadership killed in action, the survivors only just managed to scramble back to the mountains.

Ibn Tumart died shortly after in August 1130, and it is a tribute to his well-organised social structure at Tinmel that his movement carried on with a new leader. There was probably a power struggle of some kind, but Abd al-Mu'min, Tumart’s closest friend took command, and in a staggering tour-de-force in the nineteen years between 1130 and his death in 1163, Mu'min not only removed the Almoravids, but extended his power over all northern Africa as far as Egypt, becoming Emir of Marrakesh in 1149. He turned his attention to al-Andalus in 1146 and broke the grip of the Almoravids across Iberia, moving the capital of their rule from Córdoba to Seville. The Torre de Oro on the banks of the old docks was one of many fortifications built by the Almohads.

Torre de Oro Torre de Oro

After the death of Mu'min, Abu Yaqub Yusuf (Yusuf I) became emir and ruled from 1163 until his death in 1184. He ordered the construction of a great mosque in Seville, and upon his death, the great minaret, which is now known as the Giralda, was constructed to celebrate the accession of his successor, Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur. They also built a palace in Seville called al-Muwarak on the site of the modern day Alcázar.

The Giralda, Seville The Giralda, Seville

Almohad intolerance in the treatment of Christians and Jews drove many of them out of al-Andalus into the growing Christian states in the north. Over the years, they became less fanatical, but the damage had been done, and the dispossessed became adversaries. The brother of the emir, Abu Yahya, was governor of al-Andalus whilst the emir ruled from Marrakesh, and a truce had been in force with the Christians, but when the emir fell ill in 1194, his brother dropped everything and rushed to Marrakesh hoping to take over as emir.

With al-Andalus ungoverned, Alfonso VIII of Castile attacked Seville. The Christian forces were led by the Archbishop of Toledo and the Order of Calatrava, and they ransacked the province. A fully recovered and furious Abu Yusuf Yaqub returned to Seville the following year at the head of an army with the intention of striking back at the Christians. Having had advance warning, Alfonso gathered his forces at Toledo and marched down to Alarcos, (al-Arak) near the Guadiana River. Yaqub met him there, but rested his forces for two days before engaging the enemy. The battle was ferocious and lasted all day, but in the end, the emir had driven the Christians into the castle at Alarcos and surrounded them. Half of the 3,000 people in the castle were women and children and their leader, Diego López de Haro, Lord of Vizcaya, negotiated for surrender. The survivors were allowed to go, leaving 12 knights as hostages for the payment of a great ransom.

The Castilian field army had been destroyed, and many of the Christian nobles had been killed as well as the knights of the Order of Calatrava. The emir had also lost many of his closest supporters, but he had earned the agnomen of al-Manṣūr, the Victorious. Pope Innocent III considered the defeat such a threat to Christendom that he called to the Spanish, French and Portuguese nobles to mount another crusade.

For the next two years, al-Mansur's forces devastated Extremadura, the Tagus valley, La Mancha and even the area around Toledo. Many of the expeditions against the Christians were led by Pedro Fernández de Castro, a turncoat and enemy of King Alfonso. But the attacks produced no real gains in reclaiming lost territory. However, the Christian kingdoms had been devastated, which led to Navarre proclaiming neutrality, and a peace treaty with King Alfonso IX of León, who had been enraged when the Castilian king had not waited for him before the battle of Alarcos.

The treaties and alliances were all temporary, but good enough for the emir to claim success. Abu Yusuf Yaqub returned to Marrakesh in poor health, and he died there in 1199. Abu named his son, Muhammad al-Nasir as successor. Sixteen years later, the new caliph began a new Iberian offensive, but on the 16th July 1212 he came upon a force that was prepared for his arrival. He was facing the armies of three kingdoms, Castile-Leon, Aragon, and Navarra, plus some Portuguese troops and military orders including the Knights Calatrava and Templar. This force of 50,000 was headed by the King of Castile, Alfonso VIII, assisted by Pedro II of Aragón and Sancho VII of Navarra.

According to legend, a local shepherd named Martin Halaja showed the Christian forces a way to cross the 480km-long Sierra Morena Mountains through a gorge unknown to the Almohads. The attack took the Moors by surprise and allowed the Christians to surround the tent of the caliph, and he narrowly he escaped capture. Nevertheless, the Christian armies had the advantage of surprise against the 200,000 strong army of Nasir. Muslim chroniclers attribute the defeat to the greed of the caliphs, and Andalucian traitors and cowards who were supposed to be fighting for their Almohad rulers. In truth, it was marked by betrayals on both sides. Now known as the Battle of Tolosa, the conflict marked the turning point in the reconquest of Iberia. Historians emphasize the ruthless Christian violence which characterised the battle, and the bloodthirsty cries of King Alonso’s heralds during the battle, “Slay and seize. If you take a prisoner, you will be killed with him."

This painting of the Battle of Tolosa was painted by Francisco de Paula Van Halen and hangs in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. This painting of the Battle of Tolosa was painted by Francisco de Paula Van Halen and hangs in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

When the battle was over, the Christians had routed the Almohad army, and the defeat was to mark the turning-point that led to the end of Moorish rule in the Iberian Peninsula. The Almohad Empire itself collapsed a few years later after internal bickering and multiple power-grabs.

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 5:00 AM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|