Locked in the dark with 18 000 bats and 30.000 year old human remains

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

Present day entrance, discovered in 1924 Present day entrance, discovered in 1924

I simply cannot fathom why some people love to repel themselves hundreds of meters into caves and squeeze themselves through even darker cracks into airless underground chambers. Yet, somehow, I found myself voluntary locked into an unlit cave amongst million-year-old stalagmites and petrified human remains, and loving it! Meet La queva de la Pileta:

In 1905, an Andalucían sheep farmer called José Bullón Lobato noticed a swarm of bats flying around a mountainside. Since bat droppings are good fertilizers he climbed up locate the source, hoping to use the droppings for his olive trees. He found an opening in the mountain with a deep chasm. Returning with rope and a torch, he let himself down to discover an enormous cave with mysterious markings on the walls. He guessed that these were the work of the Moors, some 800 years back. He was off by over 20.000 years!

The discovery of La Cueva de la Pileta (the Cave of the Pond) changed the lives of his family. They bought the land where the cave was located and started studying the cave paintings together with international scientists. In 1924, the cave became a Spanish national monument, though still owned and cared for by the family. Only in the last decades has it been open to the general public. While the first scientist accessed the area on horseback, today it is considerably easier. The cave is located about 30 minutes drive from Ronda and we brought a willing visitor along. From the parking lot, we climbed the 101 stone steps leading to the cave entrance. (Thankfully the family discovered this second entrance in 1924, so we needed neither rope nor repelling gear.) The discovery of La Cueva de la Pileta (the Cave of the Pond) changed the lives of his family. They bought the land where the cave was located and started studying the cave paintings together with international scientists. In 1924, the cave became a Spanish national monument, though still owned and cared for by the family. Only in the last decades has it been open to the general public. While the first scientist accessed the area on horseback, today it is considerably easier. The cave is located about 30 minutes drive from Ronda and we brought a willing visitor along. From the parking lot, we climbed the 101 stone steps leading to the cave entrance. (Thankfully the family discovered this second entrance in 1924, so we needed neither rope nor repelling gear.)

For those who search for authentic nature experiences, La Pilta is completely undeveloped. There is no gift shop and no set tour-schedule. Our guide, the grandchild of the discoverer, is the fourth generation to care for the cave, a legacy he does not take lightly. He waited until a group of about a dozen people had gathered, then unlocked a heavy padlock and opened the double door with steel bars covering the entrance. By muted torchlight he collected the entrance fees. Since the cave has no electric lighting, he handed every couple of visitors a small portable lamp. Then he locked the gate behind us, to assure that nobody could enter, or exit for that matter…

He informed us of the strict rules to minimize the impact of visitors in this sensitive environment. No loud sounds, no touching walls or geological formations, and absolutely no cameras or videos, all of which can deteriorate the cave paintings and stone formations that have taken millennia to form. It may also dstroy or altr a very sntitive eco systm within the cave, containing some water beetle species that are found nowhere else on this planet. Electric light, he told us, bleaches the natural mineral deposits that give the amazing variety of colours to the cave walls. (In the floodlit theme-park-style caves of Gibraltar or Nerja near the coast, one can see examples of this deterioration) As we accustomed ourselves to moving in semi-darkness, an amazing underground world lay before us. La Pileta is truly a living cave. We heard trickles of water everywhere. And the flurry of bat wings. The cave is the home to 18 000 bats, though not the Dracula blood sucking type, we were assured. Besides, at the time of our visit most of them were at work, catching other tasty morsels. He informed us of the strict rules to minimize the impact of visitors in this sensitive environment. No loud sounds, no touching walls or geological formations, and absolutely no cameras or videos, all of which can deteriorate the cave paintings and stone formations that have taken millennia to form. It may also dstroy or altr a very sntitive eco systm within the cave, containing some water beetle species that are found nowhere else on this planet. Electric light, he told us, bleaches the natural mineral deposits that give the amazing variety of colours to the cave walls. (In the floodlit theme-park-style caves of Gibraltar or Nerja near the coast, one can see examples of this deterioration) As we accustomed ourselves to moving in semi-darkness, an amazing underground world lay before us. La Pileta is truly a living cave. We heard trickles of water everywhere. And the flurry of bat wings. The cave is the home to 18 000 bats, though not the Dracula blood sucking type, we were assured. Besides, at the time of our visit most of them were at work, catching other tasty morsels.

In the first ‘gallery’, a natural chimney was used as an enormous hearth during the Bronze Age. Further into the cave we would see soot deposits from smaller fires, as there was natural ventilation there. Moving along the slippery ground, I felt as if we were walking on a petrified composite of human remains. And we probably were. Both Paleolithic and Neolithic Man occupied this cave for long periods of time. Fragments of pottery have been found, as well as several skeletons. Amongst these was a stout and muscular man of the early Neolithic European race. La Pileta was thus one of the places where the first Homo sapiens sapiens made their home after crossing over from Africa. The Carbon 14 testing can only test back 32 000 years, but newer scientific equipment can go further back and date the finds more accuratly.

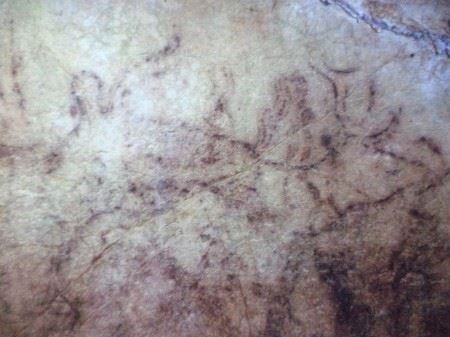

Not only did the cave dwellers live there. Our prehistoric relatives also made amazing art from clay, minerals and animal fat. 134 paintings, black, ochre and red, have been found, some five times older than the Egyptian pyramids and many quite inaccessible, even now. How did our ancestors manage this?

I was surprised that the 20 - 32.000 year old drawings were more naturalistic and seemed ‘better’ than the newer charcoal drawings dating back ‘only’ 4 - 8000 years. The older drawings made by Cro-Magnon Man in the upper Paleolithic period, showed horses, goats and bison, often to perfect scale. There was even a giant reindeer, which meant that people found shelter here during at least one ice age. The Neolithic drawings, said to be of the Levantine school, were mostly lines (counting winters stuck in the cave?), zigzag patterns and stick men of more symbolic natire. Some looked like Robinson Crusoe style primitive calendars. I was surprised that the 20 - 32.000 year old drawings were more naturalistic and seemed ‘better’ than the newer charcoal drawings dating back ‘only’ 4 - 8000 years. The older drawings made by Cro-Magnon Man in the upper Paleolithic period, showed horses, goats and bison, often to perfect scale. There was even a giant reindeer, which meant that people found shelter here during at least one ice age. The Neolithic drawings, said to be of the Levantine school, were mostly lines (counting winters stuck in the cave?), zigzag patterns and stick men of more symbolic natire. Some looked like Robinson Crusoe style primitive calendars.

The change from figurative to abstract art indicates that form and fashion altered through these millennia. In fact, the Late Old Stone Age art of Andalucía is very similar to

that found in southwestern France and northern Spain. Does this mean that there were traveling art teachers back then?

We continued up and down along 243 slimy steps, carved into the ground in the 1920’s. In the narrowest passages, the larger members of our group had to squeeze though with only millimeters to spare and duck to avoid stalactites. We passed by a couple of shallow underground pools, or piletas. Our guide explained that the cave system was originally an underground river dug out of the limestone. In dry periods stalactites and stalagmites formed, while in wet periods the cave was flooded with water, explaining why some of the walls have been worn smooth. Some visitors seemed to worry about a sudden flash flood. After all, we were locked into the mountain with only a few measly lamps between us. Our guide smiled, “Maybe not today…”

Up close we could see tiny droplets carrying microbes of limestone attaching themselves to the bottom of stalactites, eventually falling and forming a stalagmite below. It takes about a century for a stalagmite to grow a mere milimeter – that is unless the drop comes down too quickly, eroding instead of adding to it. We were told the names of some of the rock formations, but I was too busy trying to stay on my feet and lighting the way for an almost legally blind co-visitor to take much note. Up close we could see tiny droplets carrying microbes of limestone attaching themselves to the bottom of stalactites, eventually falling and forming a stalagmite below. It takes about a century for a stalagmite to grow a mere milimeter – that is unless the drop comes down too quickly, eroding instead of adding to it. We were told the names of some of the rock formations, but I was too busy trying to stay on my feet and lighting the way for an almost legally blind co-visitor to take much note.

Our walk ended 500 meters into the mountain in a hall with a 50-meter-high ceiling and a 20,000 year-old drawing of a fish on the wall. Our guide stomped on floor and the sound reverberated underneath us. Wasn’t that the ground that moved? He told us that there was a larger yet hall right underneath us, and the layer between the two halls was only four meters thick, creating a disturbingly realistic echo. The group eyed each other with looks of ‘Let’s get out of here!’

We had hardly walked a fraction of the explored caves, only what now is accessible and considered safe – not safe for the general public, but for the cave paintings and geological formations. Back outside, after buying a couple of post cards by candle light, I could honestly say that it had been thrilling and that this would not be my last cave. It was a true privilege to be taken on a journey of 30.000 years of prehistoric art, even more so when it was guided by a family-member of the man who re-discovered the cave a century ago.

The province of Cádiz alone has several hundred unexplored caves with paintings, most of which have been closed up by the government. La Cueva de La Pileta is the only National Monument cave in Spain that is under private ownership. For decades, the government has tried to take it over. The Bullón Lobato family has guarded La Pileta with outmost care for four generations, assuring that the sensitive environment is not damaged. Thanks to strong support from both geological and archeological specialists from around the world, the family is still the owner and caretaker of the cave. For for information, go to www.cuevadelapileta.org

Note: The Pileta photos on this blog post are from postcards or from the entranc of the cave. The interior cave photos were taken at the cave in Gibraltar where photographing is allowed.

A 4-meter-long, 20.000 year-old cave drawing. Note the contour of a perfect seal in its perimeters.

0

Like

Published at 8:31 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 8:31 PM Comments (0)

Surprise! Buying a Spanish house and discovering we have quintuplets

Monday, September 14, 2015

Had this story been by Dickens, this chapter would have been called; Chapter two. Where the narrative reverts the circumstances by which a house was purchased, introducing the curious inhabitants and contents found therein, comprising further particulars of the pleasant old gentlewoman who had forgotten how to write her name. However, since it is not, I will limit myself to one-liner headings. Alas, I digress…

In Spain one can often read of house-buyers who once taken possession of their new abodes discover that all the things that made them fall in love with the place; the chandeliers, the mantle, the doorknobs and other details are all gone. Ronda is rather the opposite, particularly if one buys a house from locals. Whether it is sold furnished or not, one can expect to be left with the former owners undesirables, and, if one is lucky, a few treasures.

Some friends bought a finca outside of town from a restaurant owner. They did not only inherit dishes for a party of 300 and food in the fridge, but also a fully stocked wine cellar. Another couple we know bought a house in the historic quarter of Ronda, including a ton of old ladies clothes. Instead of dumping the entire mothball infested wardrobe, the new owner cleaned and folded everything, bringing them by the carload to a local charity. One day she came upon a couple of brooches on a lapel. She took them to a jeweller who confirmed that they indeed were gold with diamonds and other precious stones. I love this story, as if the ghost of a former owner thanked her for respecting her things and doing a decent thing with them. (Note to ye BBC Antique Roadshow watchers – the brooches have not been sold)

Our house was another story. Upon first viewing it could look rather daunting to someone of less shall we say adventurous spirit. It was about three meter (ten feet) wide, though the house did not contain a single straight wall or remotely flat surface. It was actually the last original house on the street, having meter thick walls, tiny dark rooms, just a couple of dingy windows, odd steps leading up and down without rhyme or reason, an incredibly narrow stairs to the second floor (each step of different height), a rotted roof with ‘natural skylights’ and a wall clearance on one end of about 50 centimeters, a mouldy basement that would drip undefined substances upon your head, and finally, down and up another stairway, a small terrace, partly covered by carcinogenic concrete roofing. On the plus side, it did have lovely moss-grown Arab roof tiles and a great view with a silhouette of the old city wall against the sky. We went back again to see it with fresh eyes the next day to be sure we did not need to give our heads a shake. I think it was the tailless salamander that scuttled off into the dust when we kicked the warped metal entrance door open that made us decide. A view and a resident salamander, what else could one want? This house was perfect. Well, could be, given a bit of imagination and a tad of work. Our house was another story. Upon first viewing it could look rather daunting to someone of less shall we say adventurous spirit. It was about three meter (ten feet) wide, though the house did not contain a single straight wall or remotely flat surface. It was actually the last original house on the street, having meter thick walls, tiny dark rooms, just a couple of dingy windows, odd steps leading up and down without rhyme or reason, an incredibly narrow stairs to the second floor (each step of different height), a rotted roof with ‘natural skylights’ and a wall clearance on one end of about 50 centimeters, a mouldy basement that would drip undefined substances upon your head, and finally, down and up another stairway, a small terrace, partly covered by carcinogenic concrete roofing. On the plus side, it did have lovely moss-grown Arab roof tiles and a great view with a silhouette of the old city wall against the sky. We went back again to see it with fresh eyes the next day to be sure we did not need to give our heads a shake. I think it was the tailless salamander that scuttled off into the dust when we kicked the warped metal entrance door open that made us decide. A view and a resident salamander, what else could one want? This house was perfect. Well, could be, given a bit of imagination and a tad of work.

Some time later we were meeting the owner at the notary office to sign over the house. We were led into a boardroom as various people started to enter. First, a woman with a very ample behind. The owner, we wondered? Next, another women, also with a broad reach. Then came a short and stocky man with an equally stocky but very pretty boy. Finally, yet another woman with the same familiar rear (had to be sisters) leading a very old lady by the arm. As introductions were made, we realized that we were in the presence of four generations and possibly the closest living relatives of the owners. The old lady touched my hand and started telling me all kinds of things in her Andalucian dialect. I nodded and smiled, not understanding a thing, except what I could gather from the wetness of her eyes and her soft smile. Later it became clear that she and her late husband were the owners. The notary entered with a bent back and a thick stack of papers, which were to be viewed and signed on each page by seller, buyer and legal representative. We signed, the notary signed, but the old lady, 92 and counting, could no longer remember how to sign her name. It is probably rare that woman of her age in rural Spain know how to write at all. Her niece wrote the name on a piece of paper and following what she saw the old lady wrote her name with a long slow scratch. Josepha. Some time later we were meeting the owner at the notary office to sign over the house. We were led into a boardroom as various people started to enter. First, a woman with a very ample behind. The owner, we wondered? Next, another women, also with a broad reach. Then came a short and stocky man with an equally stocky but very pretty boy. Finally, yet another woman with the same familiar rear (had to be sisters) leading a very old lady by the arm. As introductions were made, we realized that we were in the presence of four generations and possibly the closest living relatives of the owners. The old lady touched my hand and started telling me all kinds of things in her Andalucian dialect. I nodded and smiled, not understanding a thing, except what I could gather from the wetness of her eyes and her soft smile. Later it became clear that she and her late husband were the owners. The notary entered with a bent back and a thick stack of papers, which were to be viewed and signed on each page by seller, buyer and legal representative. We signed, the notary signed, but the old lady, 92 and counting, could no longer remember how to sign her name. It is probably rare that woman of her age in rural Spain know how to write at all. Her niece wrote the name on a piece of paper and following what she saw the old lady wrote her name with a long slow scratch. Josepha.

There is a story that has been told to us after about Josepha’s husband Salvador. He was a hero, fighting for the resistance during the Spanish civil war. However, such people were not recognized while Franco was alive. Only after the dictator’s death in 1975 did Ronda acknowledge the town’s heroic son by renaming our street Calle Salvador Marin Carrasco. There is a story that has been told to us after about Josepha’s husband Salvador. He was a hero, fighting for the resistance during the Spanish civil war. However, such people were not recognized while Franco was alive. Only after the dictator’s death in 1975 did Ronda acknowledge the town’s heroic son by renaming our street Calle Salvador Marin Carrasco.

Signed, stamped (the Spanish love their seals and signatures) and paid, the house was ours including all it’s content, amongst other a decomposed Iberian ham hanging from its hairy hoof on a ladder, several large boxes containing walnuts, what looked like a double-header home-made mouse trap and old mirrors placed vicariously or deliberately on almost every wall, possibly to appease some ghost? We were told that the last resident was blind. Judging by the many editions of free religious calendars scattered around the house, we calculated that the old lady must have passed away some time between 1986 and 1988. Was the ham from then, I wondered? It was incredible that a blind person had lived alone in this house, without a kitchen (using a hotplate in the basement?) without bath or shower, with loose steps, uneven floors and perilous electric wiring.

It was around this time that my parents announced that they were coming to visit us. Dad had cancer, but had been given a green light to travel between chemo treatments, so time was of the essence. I immediately started a frenetic clearing out process. In the matter of days, we had hauled at least 80 black mega garbage bags to the containers up the street. Furniture and other items that we thought could be useful to somebody we left beside of the containers. Even the 1971-style potty chair on wobbly wheels was snapped up before we arrived with the next load. Somebody must have a bedridden grandparent.

Since we did not know how many decades the walnuts had been sitting in the house, we also decided to throw out the boxes. Lifting the last one, I heard scratching inside. Rodents, I thought, letting go. There was more scratching and some strange almost baby-like crying, so I peaked inside, discovering a batch of newly born kittens. One. Two. Three. Four. No. Five. We had gotten ourselves quintuplets! This presented a bit of an issue, because the house was to be gutted as soon as we had a permit. The critters had to be moved and soon, yet our rental house didn’t allow pets, even if I had not been allergic to cat hair. We had to count on maternal instinct instead. The mother must have been one of the local street cats seemingly in a perpetual state of pregnancy. We moved the box carefully beside the broken front window where she entered to feed her young. Before we went to pick up my parents at the airport we checked in on our quintuplets. The box was empty. Thank heavens, we thought! Since we did not know how many decades the walnuts had been sitting in the house, we also decided to throw out the boxes. Lifting the last one, I heard scratching inside. Rodents, I thought, letting go. There was more scratching and some strange almost baby-like crying, so I peaked inside, discovering a batch of newly born kittens. One. Two. Three. Four. No. Five. We had gotten ourselves quintuplets! This presented a bit of an issue, because the house was to be gutted as soon as we had a permit. The critters had to be moved and soon, yet our rental house didn’t allow pets, even if I had not been allergic to cat hair. We had to count on maternal instinct instead. The mother must have been one of the local street cats seemingly in a perpetual state of pregnancy. We moved the box carefully beside the broken front window where she entered to feed her young. Before we went to pick up my parents at the airport we checked in on our quintuplets. The box was empty. Thank heavens, we thought!

Of course, the first thing my parents wanted was to see our new home. Even before we got to Ronda, I asked them to promise that they would not be shocked, or I would not give them the tour. My parents gave their word, mumbling that it could not be that bad… Now, it has to be added that Norwegians usually live in large houses with windows and doors that close hermetically and everything working predictably and functioning faultlessly, as one might suspect of Scandinavian design. Having our trepidations, we avoided the house visit for as long as we could. Finally on their last day, the subject could no longer be avoided. We pacified them with sangria and a hearty lunch before the site viewing. Since we had bought the house next door, it wasn’t a far walk. Once we had kicked open the door and dad had to bend head and upper back to get inside, reality started to dawn upon them. We took them from tiny room to tinier room, warning them alternately to watch their steps and their heads. Passing the bedroom, we discovered two of the kittens motionless on the stained straw mattress. Probably lacking milk for all five, the mother must have placed her departed kittens carefully there. It was a touching and sad sight, and did not aid my parents’ silent, but very clear opinion about our home. Having gotten them safely out, mom suggested that might we not have bought something a bit over our heads? Oh no, we said, this would be an easy fix (ha!) Where would our garden be, they wondered? We pointed to the fields all around. And what about when you have dining guests, they inquired, their own dining table allowing 18 guests. We said that we would get a table for four and if we were more plentiful, we would go to the restaurant up the street. Mom and dad went back to Norway, probably completely abhorred, though not saying anything more.

Alone once again, we calmly explored our 3-meter-wide slice of Andalucian paradise, unearthing treasures such as terra cotta olive jugs (decomposed olives included), a lovely old iron bed, handmade grass baskets and several farm chairs. I certainly would not lack restoration projects while we waited for our building permit. And that could not take that long, could it?

To find out what happened next, look for the next blog chapter: Permit. What permit? Waiting for papers in Spain.

1

Like

Published at 10:05 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 10:05 AM Comments (0)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|