The magical cork and why every self-respecting wine should want one

Friday, January 29, 2016

People may say what they like about the advantages of plastic corks and screw tops (lets not even talk about wine in Tetra packs…), but to me a well-made wine merits a real cork. I am not a wine snob, but probably a bit of a traditionalist. Particularly these days when everything is about convenience, it is important to keep some of the old rituals, such as the simple joy of pulling a cork out of a wine bottle. Hauling a wad of plastic out of your favourite vintage simply cannot compare. There is the earthy smell of the cork, the little squeaky sounds as one wiggles and pulls and finally the little pop as the cork emerges from the bottles’ neck. A perfect tool for the job, having served us for centuries, with still no man-made competitor when it comes to the longevity of real cork. People may say what they like about the advantages of plastic corks and screw tops (lets not even talk about wine in Tetra packs…), but to me a well-made wine merits a real cork. I am not a wine snob, but probably a bit of a traditionalist. Particularly these days when everything is about convenience, it is important to keep some of the old rituals, such as the simple joy of pulling a cork out of a wine bottle. Hauling a wad of plastic out of your favourite vintage simply cannot compare. There is the earthy smell of the cork, the little squeaky sounds as one wiggles and pulls and finally the little pop as the cork emerges from the bottles’ neck. A perfect tool for the job, having served us for centuries, with still no man-made competitor when it comes to the longevity of real cork.

The cork oak, a native tree of the Mediterranean, have been around for about 150 million years. Here in southern Spain, there is evidence that people worked with cork since about 4,000 BC. The Greeks, the Phoenicians, and later the Romans used cork as a sealant, enclosing their wines and other liquids in clay containers. However, it was not until the 17th century that a French Benedictine monk named Dom Pierre Pérignonreplaced the wooden peg formerly used and tried a cork as a bottle stopper. And corks have been produced basically the same way ever since. The cork oak, a native tree of the Mediterranean, have been around for about 150 million years. Here in southern Spain, there is evidence that people worked with cork since about 4,000 BC. The Greeks, the Phoenicians, and later the Romans used cork as a sealant, enclosing their wines and other liquids in clay containers. However, it was not until the 17th century that a French Benedictine monk named Dom Pierre Pérignonreplaced the wooden peg formerly used and tried a cork as a bottle stopper. And corks have been produced basically the same way ever since.

The job of a wine closure is to keep the wine in and oxygen out, as simple as that. Wine types, laws and regulations, tradition, current fashion and last but not least cost all influence the bottle closures selected by the producer. Alternative wine closures came quite recently onto the scene. Screw caps have been around since the mid-sixties and are generally used by New Zealand and Australian wine producers. Plastic and synthetic stoppers are rapidly replacing natural cork. On a global level, most wines now favour synthetic corks, though these types of bottle sealants are not suited for long-term storage. So, is this tendency all about the mighty buck?

Wine closure alternatives were developed by winemakers wanting to prevent loss due to ‘cork taint’, when a wine gets spoiled by air penetrating the cork. ‘Cork taint’ affects about 3% of wines using traditional cork, making it seem like an undependable choice to some producers. (Yet, have you ever seen a champagne bottle with a plastic cork?) Due to its natural growth and harvest, corks are 2-3 times more expensive than the synthetic alternatives. Being a natural product, the quality vary, and producers may choose a lower grade cork to save cost. Some of the alleged drawbacks of natural cork may be blamed on the lower grade technical agglomerated cork products, which is a bit like comparing particle-board and MDF to hardwood. And as with real wood, you have to pay for quality. Wine closure alternatives were developed by winemakers wanting to prevent loss due to ‘cork taint’, when a wine gets spoiled by air penetrating the cork. ‘Cork taint’ affects about 3% of wines using traditional cork, making it seem like an undependable choice to some producers. (Yet, have you ever seen a champagne bottle with a plastic cork?) Due to its natural growth and harvest, corks are 2-3 times more expensive than the synthetic alternatives. Being a natural product, the quality vary, and producers may choose a lower grade cork to save cost. Some of the alleged drawbacks of natural cork may be blamed on the lower grade technical agglomerated cork products, which is a bit like comparing particle-board and MDF to hardwood. And as with real wood, you have to pay for quality.

Cork advocates argue that alternatives don’t allow the alcohol to breathe naturally. Cork is the single best natural product malleable enough to hold content inside a glass bottle. A substance found in the cork cells stops the passage of air and liquid through the cork. Natural cork bottle enclosures have many advantages: they are natural, flexible and compressible, with amazing anti-slip properties. It is biodegradable, recyclable and grows in the wild, thus promoting biodiversity. Unlike synthetic closures, a natural cork expands and contracts with a slightest temperature fluctuations, maintaining a perfectly tight seal, even as the glass of the bottle itself also minutely changes.

Cork is the prime choice for long-term wine storage, where the present alternatives cannot compete. As a testament to the amazing sealant qualities of natural cork, imagine the incredible pressure the bottles found in the Titanic wreckage had been exposed to, still with the corks intact! In 2010, a ship was found at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, 50 meters blow sea level, containing 169 bottles of champagne, having survived since the mid-19th century and apparently being quite quaffable, at that. The darkness, plus constant, low temperature are perfect aging conditions for wine, which is why some producers, such as Ronda’s organic wine producer Schwartz, are experimenting with storing some of their best vintages under water. Cork is the prime choice for long-term wine storage, where the present alternatives cannot compete. As a testament to the amazing sealant qualities of natural cork, imagine the incredible pressure the bottles found in the Titanic wreckage had been exposed to, still with the corks intact! In 2010, a ship was found at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, 50 meters blow sea level, containing 169 bottles of champagne, having survived since the mid-19th century and apparently being quite quaffable, at that. The darkness, plus constant, low temperature are perfect aging conditions for wine, which is why some producers, such as Ronda’s organic wine producer Schwartz, are experimenting with storing some of their best vintages under water.

As the worldwide demand for wine is growing and new wine markets are emerging, there isn’t currently enough cork grown to supply all producers. I am not saying that all wine needs the real thing. Just that there is a fallacy, especially in North America, where the misconception is that cork is a depleting resource and that cork trees are dying out. They are not. We are just drinking more and more, and want our wine to be cheaper and cheaper. Since the majority of cork production goes towards wine production, the real threat to cork production is the decline in demand, due to the cheaper synthetic alternatives. The WWF has actually started a cork conservation campaign, encouraging consumers to buy wine with real wine corks to help the industry stay alive. Cork extraction is one of the most environmentally friendly harvesting processes there is. Not a single tree is cut down to get the cork!

Living in inland Andalucia, we have the privilege and joy of being able to see the cork forests up close. In the mountainous, rural Western Andalucía, between the towns of Gaucin, Urbique and Ronda, and nearly all the way to Algeciras in the south, one can observe the traditional (and virtually unchanged) harvest methods of cork happening between June and August every year. The cork, which actually is a type of parasite on the bark of the trees, is carefully retrieved with special knives or hatchets, peeling away the outer cork bark, leaving the inner bark intact. The cork trees are nothing short of amazing. After the first 20 years of growth, they can produce cork for over 150 years, even though it may have been stripped at nine-year intervals. Being a cork harvester, now a special 2-year college education, is a skill handed down from generation to generation. The cork is only cut off once every nine years, allowing the trees time to regenerate. Once the ‘sheets of cork are brought to the plants, corks are stamped out by machines with different widths for wine, champagne or cognac. Living in inland Andalucia, we have the privilege and joy of being able to see the cork forests up close. In the mountainous, rural Western Andalucía, between the towns of Gaucin, Urbique and Ronda, and nearly all the way to Algeciras in the south, one can observe the traditional (and virtually unchanged) harvest methods of cork happening between June and August every year. The cork, which actually is a type of parasite on the bark of the trees, is carefully retrieved with special knives or hatchets, peeling away the outer cork bark, leaving the inner bark intact. The cork trees are nothing short of amazing. After the first 20 years of growth, they can produce cork for over 150 years, even though it may have been stripped at nine-year intervals. Being a cork harvester, now a special 2-year college education, is a skill handed down from generation to generation. The cork is only cut off once every nine years, allowing the trees time to regenerate. Once the ‘sheets of cork are brought to the plants, corks are stamped out by machines with different widths for wine, champagne or cognac.

Andalucia’s Bosque de los Alcornocales, a protected Natural Park, is Spain’s biggest plantation. However, there is nothing plantation-like at all about the cork forests. The trees grow wild amongst other oaks and natural shrubbery, often in incredible inclines where rope and donkeys have to be used to bring in the harvest, as mechanical aids would not be of much help. Spain is the worlds’ second biggest producer of cork (after Portugal) with an industry worth an estimated two billion dollars a year. With its impermeable, buoyant, elastic, and fire retardant properties, cork is also used in diverse processes from car construction to aeroplane insulation. Andalucia’s Bosque de los Alcornocales, a protected Natural Park, is Spain’s biggest plantation. However, there is nothing plantation-like at all about the cork forests. The trees grow wild amongst other oaks and natural shrubbery, often in incredible inclines where rope and donkeys have to be used to bring in the harvest, as mechanical aids would not be of much help. Spain is the worlds’ second biggest producer of cork (after Portugal) with an industry worth an estimated two billion dollars a year. With its impermeable, buoyant, elastic, and fire retardant properties, cork is also used in diverse processes from car construction to aeroplane insulation.

Clearly, preference in wine and bottle enclosures is a personal thing and there is much more to be said in this debate. But next time you grab a bottle and find a REAL cork, take a deep breath to smell its earthy past and send a small thank to the tree that offered its coat for your drinking pleasure. Cheers!

0

Like

Published at 8:26 PM Comments (1)

0

Like

Published at 8:26 PM Comments (1)

Our Annual New Years Theft – Starting the year with a very clean slate

Friday, January 15, 2016

For the past two years we have met the new-year a bit lighter. Certainly not from lack of eating and drinking during the holidays, but because somebody some place decided to pick up a few of our belongings. Though initially being victim to theft feels rather upsetting and one tends to bemoan ones losses, in retrospect it can almost feel liberating. I am not hereby advocating burglaries, nor inviting people to come and serve themselves of our dwindling earthly goods. However, at the dawn of the year, when most people have over-indulged on the material front, it is important to remember that nothing is permanent and that all things we have in our possession will at one point no longer be ours, simply a lesson in impermanence.

Last year, on the very last day of the year my wallet was picked from my bag just off Ronda’s world-famous bridge. Really, I should only blame myself for having become such a country bumpkin that I think nothing can happen in our small town. Lesson learned, cash or not, I now keep it in a double zipped pocket and hold my bag underneath my arm when walking through crowed areas. Loosing a wallet is of course very annoying. I entered the New Year not only cash less, but without a single credit card, driving license or other Ids. January first was spent on hold for hours with banks in Vancouver and Madrid and credit card call centers in Delhi or god knows where, having to answer question and disclose codes I barely could recall. Then to denounce my Spanish Ids, at the local police station, which like any Spanish office is not the ultimate in speed and efficiency. But once it was all done, I felt a strange sense of lightness. Here I was, walking about without a single piece of Id. I could be anyone. Could there be a lighter way to enter a new year?

This year, also in the first week of January we discovered that ALL our art that we had brought from Canada was gone from where we had stored it for the past year and a half. The irony was that it was kept in a local convent with cloistered nuns. Our poor nuns were beside themselves, as this had never happened in the memory of any of them, even for Mother Superior who is pushing on 90. It was unfathomable to them. Hardly anybody enters the nunnery and the few who do, are trusted by the nuns. On the other hand, doors are hardly ever locked, and treasures, be it the convents own and things stored there, can in reality be picked up and brought out along other things, should one be criminally inclined.

Initially, we were understandably upset, having lost thousands of euros worth of original art, decades in the collecting. There were priceless inherited pieces, irreplaceable old family photographs and rare and original works of art from Mexico, Canada and Norway. Many pieces where inherited or gifted to us, such as some lovely embossed limited edition bottle labels given to my husband from the Baron de Rothschild family. All gone! Friends and neighbours advised us to call the police and get fingerprints off my art portfolio that was ripped open. But sending the police and insurance agents into the nunnery was out of the question for us. It would probably give Mother Superior a heart attack. We could not do anything to hurt ‘our nuns’, who had been kind to store our boxes. We felt bad enough telling the nuns about the theft, as in the end they were more upset than us about the loss.

What to do? It was just stuff. Clearly stuff we loved and cared enough about to bring along across a large ocean. However, the art came from another chapter in our life and maybe as a new year and another page is turned, we must leave our walls bare for a while, until new art will come our way. Neither my husband nor I feel upset. We have each other, we have our health, our home and our families and friends here and abroad. What more do one need, and compared to that uncountable wealth, what is a few paintings?

If we need to experience our annual theft to be reminded of this material impermanence, I am OK with that. We cannot take it with us anyhow. And when it comes to stuff, less is almost always more, even if it sometimes hurts to realize it.

0

Like

Published at 4:54 PM Comments (1)

0

Like

Published at 4:54 PM Comments (1)

The house saga continues – De-construction and digging for dead Moors

Sunday, January 3, 2016

To demolish a house should be a rather easy affair, but not so in southern Spain. Certainly not when the house is in town where all houses are attached, so you virtually own a slice of a sidewalk with shared walls. If your house in addition is located in the historic and thus protected area, expect trouble. Our house was both; a slice with vaguely defined neighbouring walls sitting right where Ronda’s old Arab graveyard used to be located up to the late 15th century. We were at peace with our house’s friendly ghosts and felt privileged to live in such an historic area, but knew that this could cause a few delays.

Cut to two years later… Having our building permit in hand, the first thing we had to do was to apply for another permit, or to be precise, a permit extension. Not for the building, nor the demolishing, but for the archaeological dig, which they so generously had given us two weeks to complete. We’d gladly do as they said, had it not been for the rotten beams and partially caved-in roof, the treacherous stairs and shaky floors that all had to be removed, and outer walls that had to be properly checked and secured before an archaeological dig could be safely performed. But the building experts in Malaga had not foreseen this practical impossibility.

Thankfully, the extension was given without too much delay. We could in principle begin the de-construction work. There was only one more hitch. In the province of Malaga, (and no other place in Spain, as far as we know), archaeologists are only allowed to work on one project at the time. Architects and builders can juggle a handful projects to allow for technical delays, but not archaeologist. This law must exist to assure that archaeologists will starve if a work site is inevitably stalled or delayed. We contacted Ronda’s two archaeologists, who both had projects for a year or so. We started looking for archaeologists in other towns, all of whom would come with lengthy timelines and extensive projects proposals, as if we were to dig out an entire Roman village and not a 3-meter by 10-meter slice of a house at a depth of barely 40 centimeters! After a few too many ‘special price just for you’ proposals, we found an archaeologist in a nearby town who miraculously had a gap in his schedule merely two months away. We were ready to kiss his dusty sandals and signed the deal on the spot. The work could FINALLY begin. Thankfully, the extension was given without too much delay. We could in principle begin the de-construction work. There was only one more hitch. In the province of Malaga, (and no other place in Spain, as far as we know), archaeologists are only allowed to work on one project at the time. Architects and builders can juggle a handful projects to allow for technical delays, but not archaeologist. This law must exist to assure that archaeologists will starve if a work site is inevitably stalled or delayed. We contacted Ronda’s two archaeologists, who both had projects for a year or so. We started looking for archaeologists in other towns, all of whom would come with lengthy timelines and extensive projects proposals, as if we were to dig out an entire Roman village and not a 3-meter by 10-meter slice of a house at a depth of barely 40 centimeters! After a few too many ‘special price just for you’ proposals, we found an archaeologist in a nearby town who miraculously had a gap in his schedule merely two months away. We were ready to kiss his dusty sandals and signed the deal on the spot. The work could FINALLY begin.

By this time we had spoken to more constructors than we cared to remember and had found a builder whom we both felt would do a good job. He was local, second generation builder and had a family, so we knew he would not run off on us if there were any problems. Such are important things to consider when somebody is supposed to build you a house in a foreign country. His team consisted of a group of rugged men, including three very capable brothers with their specialty skills. They worked with us for almost eight months, through thick and thin as they say and we never regretted our choice. Anyhow, I am getting ahead of myself. We had not even started digging… By this time we had spoken to more constructors than we cared to remember and had found a builder whom we both felt would do a good job. He was local, second generation builder and had a family, so we knew he would not run off on us if there were any problems. Such are important things to consider when somebody is supposed to build you a house in a foreign country. His team consisted of a group of rugged men, including three very capable brothers with their specialty skills. They worked with us for almost eight months, through thick and thin as they say and we never regretted our choice. Anyhow, I am getting ahead of myself. We had not even started digging…

The thing with an old house is that one never knows what the project will entail until things are brought to the open. Walls that seem sound initially may crumble once indefinite layers of chalk paint are removed. Beams will turn to sawdust. Neighbours may have built illegal extensions and the ground may not be as solid as initially thought. There are always surprises with old houses and surprises generally cost, time and money.

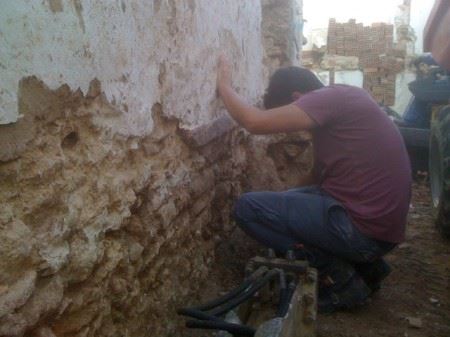

Our builders ‘moved in’, putting up an official construction sign and hanging up the legally required hard hats on the wall, never to be used as far as we detected during the entire process. Their first step was to remove the old Arab style roof tiles, one by one, carefully storing them aside to be mounted again once the new roof was built underneath. Re-using the old tiles is required in Ronda’s historic area, and both my husband and I loved the look of these patina and moss covered terra cotta tiles. Working from top to bottom, the next step was to remove all inner walls and then the dividing floors. Finally, the crumbling stairs to the second floor were removed and only the skeleton framework of three old supporting beams remained. Our architect, building inspector and builders met on the site, agreeing that things had to be taken very slowly or the sidewalls could cave in. Our builders ‘moved in’, putting up an official construction sign and hanging up the legally required hard hats on the wall, never to be used as far as we detected during the entire process. Their first step was to remove the old Arab style roof tiles, one by one, carefully storing them aside to be mounted again once the new roof was built underneath. Re-using the old tiles is required in Ronda’s historic area, and both my husband and I loved the look of these patina and moss covered terra cotta tiles. Working from top to bottom, the next step was to remove all inner walls and then the dividing floors. Finally, the crumbling stairs to the second floor were removed and only the skeleton framework of three old supporting beams remained. Our architect, building inspector and builders met on the site, agreeing that things had to be taken very slowly or the sidewalls could cave in.

As our house and the 2-meter wide slice of house to the right were once a single dwelling, probably split by siblings’ inheritance, we knew that this wall would need strengthening. We also shared the ridge beam with them, so the builders put up support buttresses next door before cutting the final beams. On the left side of our house is a multi-housing unit, which shot up during the building boom some 20 years ago. Once we stared thinning our meter-thick exterior wall, we discovered that the complex had not, as law requires, built their own exterior wall against ours, but merely leant their cross-walls against ours and ran all their cables and water pipes down our wall. As our house had been abandoned for a few decades, nobody was there to protest and we could not insist they build their wall now, 20 years later. We wrote to their strata council and were given permission to tear down and properly re-build the entire sidewall, of course out of our pocket, never mind them having broken the law. Ironically, during the entire construction period, the only complaint came from the one neighbour who had an illegal balcony leaning on our wall. Details, details… As our house and the 2-meter wide slice of house to the right were once a single dwelling, probably split by siblings’ inheritance, we knew that this wall would need strengthening. We also shared the ridge beam with them, so the builders put up support buttresses next door before cutting the final beams. On the left side of our house is a multi-housing unit, which shot up during the building boom some 20 years ago. Once we stared thinning our meter-thick exterior wall, we discovered that the complex had not, as law requires, built their own exterior wall against ours, but merely leant their cross-walls against ours and ran all their cables and water pipes down our wall. As our house had been abandoned for a few decades, nobody was there to protest and we could not insist they build their wall now, 20 years later. We wrote to their strata council and were given permission to tear down and properly re-build the entire sidewall, of course out of our pocket, never mind them having broken the law. Ironically, during the entire construction period, the only complaint came from the one neighbour who had an illegal balcony leaning on our wall. Details, details…

We were now down to the ground level. We kept what could be saved of the psychedelic hydraulic tiles that now are back in fashion which covered main floor, later donated to our builders storage, to his wife’s great annoyance. The basement and the upper floor had old terra cotta tiles, though only a dozen could be saved after indefinite years of use and abuse. Nobody actually knows how old our house is. The city plans said that it was built in 1949, which was likely when they did the last ‘renovation’. We were now down to the ground level. We kept what could be saved of the psychedelic hydraulic tiles that now are back in fashion which covered main floor, later donated to our builders storage, to his wife’s great annoyance. The basement and the upper floor had old terra cotta tiles, though only a dozen could be saved after indefinite years of use and abuse. Nobody actually knows how old our house is. The city plans said that it was built in 1949, which was likely when they did the last ‘renovation’.

Judging by the enormous hand-forged nails (enough to make a Viking jealous), at least part of the house must have been there for centuries. These types of houses have been changed, added to and morphed throughout generations, as families grew or shrunk. Our seemingly solid outer walls, a meter thick in places, were built by sticking together a mixture of oversized boulders, small rocks and red earth which once may have been clay. Equally, the house had no foundation. The walls were standing straight onto the soil with the floor tiles sitting on the earth. No strange it was a bit of a humidity problem…

The facades of houses in protected areas are supposed to be left undisturbed. This proposed a problem, as no mechanical digger could fit through our narrow front door. We had to ask for permission, once again, this time to remove the door and make a hole just wide enough for a excavator to enter. How the operator managed to actually turn the digger around inside a house no wider than 3 meter is a mystery and should in itself earn him a medal. The facades of houses in protected areas are supposed to be left undisturbed. This proposed a problem, as no mechanical digger could fit through our narrow front door. We had to ask for permission, once again, this time to remove the door and make a hole just wide enough for a excavator to enter. How the operator managed to actually turn the digger around inside a house no wider than 3 meter is a mystery and should in itself earn him a medal.

By now it was time to call on the long-awaited archaeologist. Notebook, mini brushes and putty knives in hand, he came to observe the digging, stopping the mechanical claw every time he saw a hint of something that could resemble a dead Moor or anything else worth saving. Day after day he came, picking away at the ground like a spoilt child at breakfast, and leaving walls and floors as clean enough to eat from. At long last a week later he packed up his brushes and putty knives and offered us his findings. Nothing!Nada! A few chicken bones, some pottery shards and a rusty tool-head was all he had unearthed, and a rather hefty bill. Clearly we understood that if he only could do a job at a time, he had to make as much out of the spectacle as possible. Of course the answer was NO to our next question. We could not go on with the construction before his written report had been sent to the town hall and onto the culture department, to be read, debated, hopefully approved and sealed and signed with many signatures before being couriered back to Ronda, in triplicates. By now it was time to call on the long-awaited archaeologist. Notebook, mini brushes and putty knives in hand, he came to observe the digging, stopping the mechanical claw every time he saw a hint of something that could resemble a dead Moor or anything else worth saving. Day after day he came, picking away at the ground like a spoilt child at breakfast, and leaving walls and floors as clean enough to eat from. At long last a week later he packed up his brushes and putty knives and offered us his findings. Nothing!Nada! A few chicken bones, some pottery shards and a rusty tool-head was all he had unearthed, and a rather hefty bill. Clearly we understood that if he only could do a job at a time, he had to make as much out of the spectacle as possible. Of course the answer was NO to our next question. We could not go on with the construction before his written report had been sent to the town hall and onto the culture department, to be read, debated, hopefully approved and sealed and signed with many signatures before being couriered back to Ronda, in triplicates.

Relatively speaking, we were lucky. He could have found human remains, grave posts from Moorish times or worse still, Roman coins, mosaics or column pieces? That could have stopped our dig for good. Such treasures have been found in many houses in our barrio, many quickly covered up or secretly displayed in inner courtyards. At least, with no dead Moors in site, we knew that the construction of our house could finally begin. It was just a matter of time. Relatively speaking, we were lucky. He could have found human remains, grave posts from Moorish times or worse still, Roman coins, mosaics or column pieces? That could have stopped our dig for good. Such treasures have been found in many houses in our barrio, many quickly covered up or secretly displayed in inner courtyards. At least, with no dead Moors in site, we knew that the construction of our house could finally begin. It was just a matter of time.

But that is a story for another day…

1

Like

Published at 1:36 PM Comments (2)

1

Like

Published at 1:36 PM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|