122 - Of Acorns, Olives, and Old Andaluz

Thursday, October 30, 2014

The pigs definitely won. Out of everything in this amazing multi-cultural language immersion week, the pigs definitely won. And the horses, the dogs, and the miles of rolling countryside and beautiful holm-oaks. Or maybe the food? Or perhaps achieving the challenge of a week without a single word in our own languages? Or possibly .... no, never mind. It was the pigs. The pigs definitely won. Out of everything in this amazing multi-cultural language immersion week, the pigs definitely won. And the horses, the dogs, and the miles of rolling countryside and beautiful holm-oaks. Or maybe the food? Or perhaps achieving the challenge of a week without a single word in our own languages? Or possibly .... no, never mind. It was the pigs.

Rafa lives two parallel lives, both so Spanish, both so different. He's a young business-man living in Córdoba city, cycling or walking to the office he rents to organise language immersion holidays. At the weekends he's often to be found out at the family finca on the dehesa, walking with the dogs, riding the horses, or wandering amongst the 300 Iberian Pata Negra pigs as they roam wild amongst the holm-oak trees snuffling for acorns. The city is vibrant and multi-cultural. The finca is old, nestles comfortably in the land, and takes you back to the simpler life of his parents and grand-parents and their grand-parents. In the loft where they would hang chorizos and legs of ham, there are still skins with layers of fat, drying.

Two of the three big dogs met us at the gate and led us along the track to the homestead. The six cats were feral and more wary. The horses snickered and stamped. The cows were somewhere out of sight, the occasional bell giving the only clue as to where they had chosen to graze this afternoon.  Surrounding the finca the land was reminiscent of English parkland – gently-rolling hills, beautiful trees. The October sun was warm, the grass was green, and the 500-year old trees were well-spaced so that the free-ranging pigs could wander far and wide. Rafa unlocked the big front door and we put a long table under the shade of a huge tree. Some weekends he is there with his parents, aunts and uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews for big family get-togethers, other weekends he brings city friends for a day in the campo. Surrounding the finca the land was reminiscent of English parkland – gently-rolling hills, beautiful trees. The October sun was warm, the grass was green, and the 500-year old trees were well-spaced so that the free-ranging pigs could wander far and wide. Rafa unlocked the big front door and we put a long table under the shade of a huge tree. Some weekends he is there with his parents, aunts and uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews for big family get-togethers, other weekends he brings city friends for a day in the campo.

Although born in the city after his parents had moved there, he is completely in tune with the dehesa and its history. En route we visited the Adamuz olive processing plant, run by Rafa’s cousin, Although born in the city after his parents had moved there, he is completely in tune with the dehesa and its history. En route we visited the Adamuz olive processing plant, run by Rafa’s cousin,  and the village museum where the Mayor proudly displayed his village's long involvement in olive production. A little further north and the miles and miles of olives changed to the distinctive parkland vistas of dehesa country - open, sustainable woodland, now classified as a European protected habitat. and the village museum where the Mayor proudly displayed his village's long involvement in olive production. A little further north and the miles and miles of olives changed to the distinctive parkland vistas of dehesa country - open, sustainable woodland, now classified as a European protected habitat.

Dehesa describes a traditional mediterranean silvo-pastoral system (forest / grazing) found only in the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco. The primeval forest lands were gradually encroached by ancient settlers, who thinned out the cork oaks and holm-oaks to make space for living and grazing, controlling the space through woodland management rather than man-made borders. The landscape supports lynx, wild boar, eagles and many endangered bird and plant species in the wilder parts, while in the “tamed” areas the oaks provide the essential acorns (bellota) for the Iberian pigs. Dehesa describes a traditional mediterranean silvo-pastoral system (forest / grazing) found only in the Iberian Peninsula and Morocco. The primeval forest lands were gradually encroached by ancient settlers, who thinned out the cork oaks and holm-oaks to make space for living and grazing, controlling the space through woodland management rather than man-made borders. The landscape supports lynx, wild boar, eagles and many endangered bird and plant species in the wilder parts, while in the “tamed” areas the oaks provide the essential acorns (bellota) for the Iberian pigs.

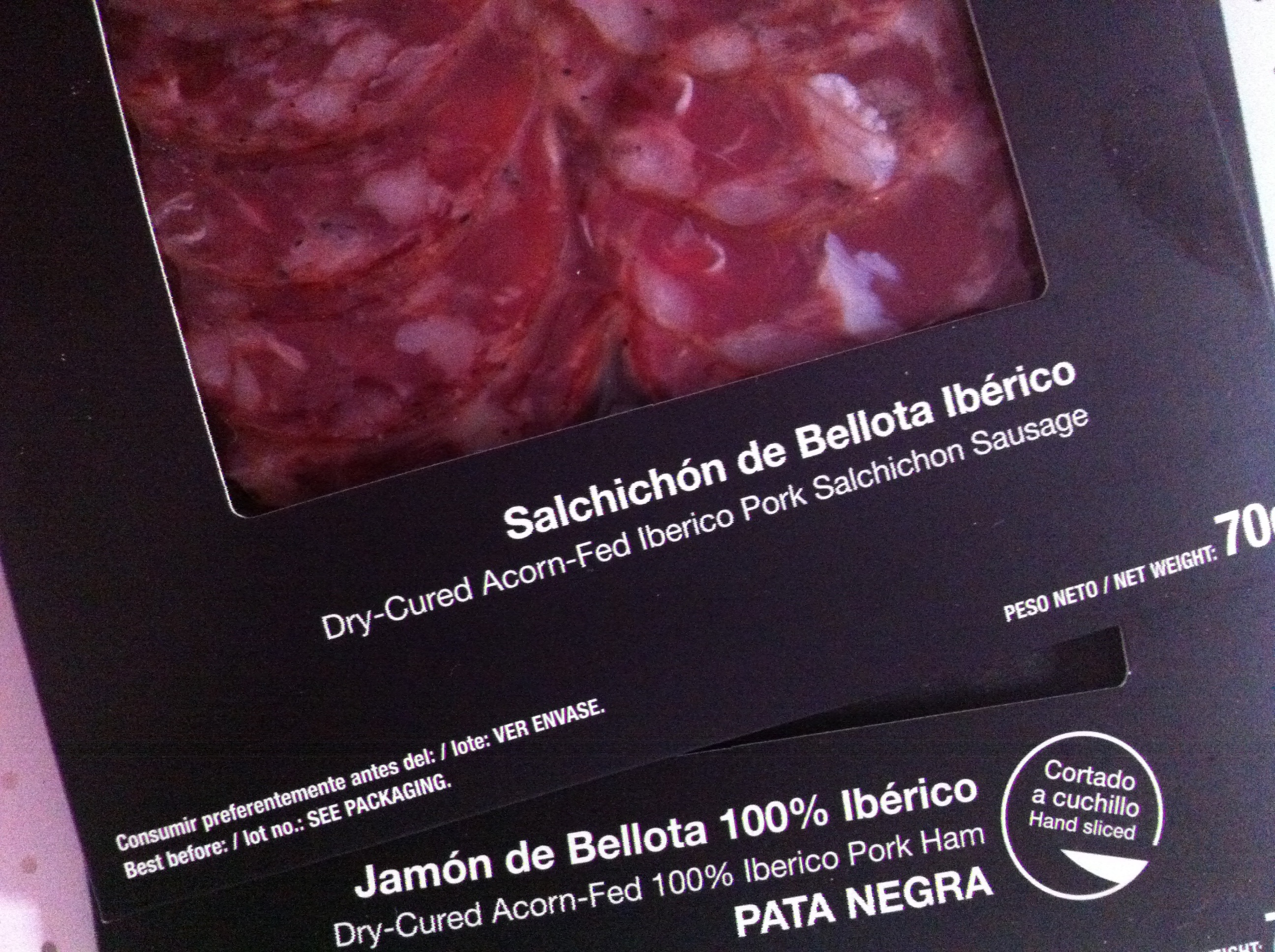

The eight of us unpacked cheese, big langoustines, bread, and sardines for the barbecue.  In the courtyard the fire was lit in two long curved roof tiles, the sardines were salted and put on to cook. Indoors in the kitchen a sharp knife rested next to the ham leg on its traditional stand. Sharing food under the shade of the big courtyard tree felt timeless. We could have been Romans or Arabs, the Andaluz farmers of any era. Tearing bread together, peeling prawns, sucking fingers burnt from the hot sardines. Slices of the precious Iberian ham, shared generously - this is the core of the dehesa - this most valuable product, the special acorn-fed jamón Iberico de In the courtyard the fire was lit in two long curved roof tiles, the sardines were salted and put on to cook. Indoors in the kitchen a sharp knife rested next to the ham leg on its traditional stand. Sharing food under the shade of the big courtyard tree felt timeless. We could have been Romans or Arabs, the Andaluz farmers of any era. Tearing bread together, peeling prawns, sucking fingers burnt from the hot sardines. Slices of the precious Iberian ham, shared generously - this is the core of the dehesa - this most valuable product, the special acorn-fed jamón Iberico de  bellota. Silky, dissolving on the tongue, heavenly. But we are spoiled now, unable ever to buy anything lesser, anything without the “de bellota” mark. bellota. Silky, dissolving on the tongue, heavenly. But we are spoiled now, unable ever to buy anything lesser, anything without the “de bellota” mark.

A perfect day, and unforgettable. The day after, October 24th, was San Rafael, Rafa's saints day (always celebrated, for some people more important than their birthday).

In the Victoria market in the city-centre park it was very tempting to shout "Rafa!" just to see how many would turn round. In the end an old Spanish man did it for me.  "Rafael!" he shouted - presumably to his friend. Seven of the eight men waiting at the jamón counter turned round. They were all either waving or fumbling for their ID cards to show the ham-seller that they were genuine Rafaels, in order to claim their free plate of the top quality jamón de bellota, on this their Saint's Day. San Rafael is also the patron saint of Córdoba, so in honour of that Covap (a co-operative of farmers in the comarca of Los Pedroches in Córdoba province) made this special offer. And with their award-winning acorn-fed ham selling at €150 to €200 a kilo, this was not to be sniffed at. The Rafaels were not going to miss their opportunity and ID cards were produced with pride. "Rafael!" he shouted - presumably to his friend. Seven of the eight men waiting at the jamón counter turned round. They were all either waving or fumbling for their ID cards to show the ham-seller that they were genuine Rafaels, in order to claim their free plate of the top quality jamón de bellota, on this their Saint's Day. San Rafael is also the patron saint of Córdoba, so in honour of that Covap (a co-operative of farmers in the comarca of Los Pedroches in Córdoba province) made this special offer. And with their award-winning acorn-fed ham selling at €150 to €200 a kilo, this was not to be sniffed at. The Rafaels were not going to miss their opportunity and ID cards were produced with pride.

Not being in the Rafael "club" I had to pay full price for my goodies. Back at home in Colmenar the delicious slivers of flavour served as a reminder of the "day in the campo", a day in the dehesa, a day understanding a little more about the history and background of Andalucía, a day speaking nothing but Spanish, a day learning to slice the precious ham, a day breaking bread in the sunshine with good friends. An unforgettable day. Un día inolvidable. Not being in the Rafael "club" I had to pay full price for my goodies. Back at home in Colmenar the delicious slivers of flavour served as a reminder of the "day in the campo", a day in the dehesa, a day understanding a little more about the history and background of Andalucía, a day speaking nothing but Spanish, a day learning to slice the precious ham, a day breaking bread in the sunshine with good friends. An unforgettable day. Un día inolvidable.

(This "day in the dehesa" was just one day in a Spanish immersion week based in and around Córdoba, organised by Rafael Terán Perez of www.experienciavivees.com. I will write more about the experience shortly.)

© Tamara Essex 2014 http://www.twocampos.com

THIS WEEK'S LANGUAGE POINT:

Lots of new words learned this week.

Bellota – acorn, but so much more important than just a Word, it becomes the mark of the best quality ham and other pork products made from acorn-fed pigs.

Dehesa – untranslatable as it doesn’t exist in English!

Trompo – spinning top (doesn’t come up VERY often in conversation …)

Mazamorra cordobesa – a white, garlicky cold soup (like salmorejo or porra but without the tomatoes).

O lo que sea – or whatever. Nice simple phrase, showing off the subjunctive (must work it into my exam, somehow!). Used at the end of a list, such as “Ella trabaja como medico, o terapeuta, o lo que sea.”

0

Like

Published at 12:54 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 12:54 PM Comments (0)

121 - Walking Under The Moon

Thursday, October 16, 2014

"Un Sendero Nocturno". A night-time walk. It had sounded beautiful. A relaxed stroll in the moonlight, chatting with 30 friends and neighbours. Starting from the next village, Casabermeja, and wandering gently up to Torre Zambra, an old Moorish lookout point and beacon, under the bright light of the October full moon, to be followed by a meal in a bar. Lovely.

The meeting-point was the village health centre, to offer lifts and share cars to Casabermeja. Bang on time (unusually for Spain) walkers began to gather. They were young. Oh, so young. Most appeared to be between 15 and 18. They were fit. The village gymnastic team had turned out in force. And they were teeny. Oh, so so teeny. In tight black leggings and teeny teeny t-shirts with lots of firm midriff on display. I felt like the elephant in the room - literally.

A few more adults turned up, all significantly younger, fitter and slimmer than me. Balta from the ayuntamiento counted us up, made sure everyone had a car to go in, and we sped off to Casabermeja. There we met the guide, Alfonso, and the walk began.

I say "walk" - but this was a sprint. The "walk" from Casabermeja centre to Torre Zambra consisted of six kilometres uphill, then the return. The teeny fit gymnasts did not appear to take a breath, nor to pause. They shot off round the first bend and I quickly realised that I was going to be right at the back, at risk of losing sight of the group, if I didn't put a spurt on.

Somewhere deep inside I found a combination of determination, experience, and bloody-minded competitiveness, and my stride quickened. Despite their extreme fitness (and did I mention their teeniness?) I knew for sure that I had thousands more hill-walking miles under my belt than they did, and that I also had the stamina that comes with age and long day-walks.

Slowly I passed the other adults, and began to close in on the leading group of teenies. Within the first kilometre I was comfortably striding along with the leaders, Alfonso calling to us to slow down a bit to wait for the middle and rear groups.

So then it was time to tackle the second problem of this excursion. I was the only British participant, and was surrounded not by the Spanish language of my CDs or my Spanish teachers, and not by the chat of my neighbours which, although lacking consonants, is marginally slower and over time has become mostly comprehensible. No - the teenies were speaking even faster than they were walking, and were using (I suppose) all the short forms, slang and colloquialisms that any group of teenagers would. They were almost entirely incomprehensible. Looking back, I spotted a group of non-teenies just behind. I dropped back a few paces to mix in with them, and (como siempre) turned the rest of this ordeal - oops, sorry, I mean "walk" - into an opportunity to listen and chat. So then it was time to tackle the second problem of this excursion. I was the only British participant, and was surrounded not by the Spanish language of my CDs or my Spanish teachers, and not by the chat of my neighbours which, although lacking consonants, is marginally slower and over time has become mostly comprehensible. No - the teenies were speaking even faster than they were walking, and were using (I suppose) all the short forms, slang and colloquialisms that any group of teenagers would. They were almost entirely incomprehensible. Looking back, I spotted a group of non-teenies just behind. I dropped back a few paces to mix in with them, and (como siempre) turned the rest of this ordeal - oops, sorry, I mean "walk" - into an opportunity to listen and chat.

The moon was yet to appear and we almost missed the last turn onto the path to the summit. One of my companions had run (!) the route before and despite the darkness we found the track and began the final ascent. Suddenly the tower appeared above us, close, shrouded in mist, and highly atmospheric. As we reached it the skies cleared and the full moon lit us as we climbed the spiral staircase onto the ramparts. The moon was yet to appear and we almost missed the last turn onto the path to the summit. One of my companions had run (!) the route before and despite the darkness we found the track and began the final ascent. Suddenly the tower appeared above us, close, shrouded in mist, and highly atmospheric. As we reached it the skies cleared and the full moon lit us as we climbed the spiral staircase onto the ramparts.

Time for a group photo then we began to descend. Just for fun a particularly steep short-cut was added which strained the knees (and even slowed down some of the teenies). There was slightly too much talk of snakes for my liking, and an outburst of screaming from the leading group of teenies sent my heart into my mouth for a moment. Something slithered away quickly, more frightened of us than vice versa.

Back in Casabermeja we trooped into La Romana where the tables were already groaning with jugs of beer, bottles of wine, lemonade, water, olives and crisps. The meal that followed was delicious but sitting down for an hour after 12 kilometres at top speed was disastrous. My car-load stood up to leave, and everything screamed - every single muscle screamed and so did we. We hobbled painfully outside, feeling truly ancient, leaving the teenies presumably ready to head on to dance the night away in a club. A great walk, one I would definitely repeat, but next time the "walk" really WILL be a walk. Back in Casabermeja we trooped into La Romana where the tables were already groaning with jugs of beer, bottles of wine, lemonade, water, olives and crisps. The meal that followed was delicious but sitting down for an hour after 12 kilometres at top speed was disastrous. My car-load stood up to leave, and everything screamed - every single muscle screamed and so did we. We hobbled painfully outside, feeling truly ancient, leaving the teenies presumably ready to head on to dance the night away in a club. A great walk, one I would definitely repeat, but next time the "walk" really WILL be a walk.

© Tamara Essex 2014 http://www.twocampos.com

THIS WEEK'S LANGUAGE POINT:

Right, so last week I learned how to describe what I could see in the different areas of a photo. During the week I have singularly failed to put this useful new skill into practice.

This week's task is to go on to describe what I think the people in the photo might be doing. Inevitably the photo will leave this slightly unclear, so we get to use all those phrases about uncertainty. And what does uncertainty trigger? Yes, the good old subjunctive (no groaning, please).

Firstly I will be expected to mention a few things about which I have a reasonable degree of certainty, which do NOT use the subjunctive.

To differentiate, I always call to mind JuanMi's brilliant lesson in which he jumped to the right-hand corner of the classroom (la esquina derecha) to say we definitely think something IS so, then to the left-hand corner (la esquina izquierda) if we think it definitely ISN'T so, and then hovered in the middle (en el centro) for when we aren't sure enough to bet a euro on it. That's where the subjunctive is.

(I wrote up JuanMi’s lesson in “A Bad Case of Subjunctivitis” )

So I have to start with:

A mi me parace que estan hablando - It seems to me they are talking (reasonable certainty).

Probablemente ella le esta mostrando algo - Probably she is showing him something (reasonable certainty).

Then I have to start guessing at the detail:

Puede que esten hablando sobre un email - It could be that they are talking about an email (subjunctive).

Quizás hayan recibido una foto graciosa - Perhaps they have received a funny photo (subjunctive).

0

Like

Published at 11:44 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 11:44 AM Comments (0)

120 - Reddest, Greenest, Tastiest ....

Thursday, October 9, 2014

I'd heard it a million times. Gardeners, exaggerating how marvellous their fruit and veg were. Fisherman's tales of everything being greener, bigger, rounder, smoother, and above all, so much BETTER than everything we poor  mortals were buying. Yawn. Until my awakening. Until that Damascene moment. Until I ate the first tomato from my own plant. mortals were buying. Yawn. Until my awakening. Until that Damascene moment. Until I ate the first tomato from my own plant.

Oh how boring I shall become! Because, you know, it really is true! They simply ARE redder, and more beautiful, and warm from the sun, and more delicious than any tomato has ever been. Ever. Sliced or in wedges, with a sprinkle of salt or my neighbour's strong olive oil. Nothing better.

And my peppers!!! Oh my goodness, how extraordinary they are. Nearly all bent in the middle, where as a tiny baby they grew against a leaf, whose greater strength forced the soft baby pimiento to twist away from it. Mis-shapen, unloved by supermarkets, and delicious in our weekend paella. And my peppers!!! Oh my goodness, how extraordinary they are. Nearly all bent in the middle, where as a tiny baby they grew against a leaf, whose greater strength forced the soft baby pimiento to twist away from it. Mis-shapen, unloved by supermarkets, and delicious in our weekend paella.

I have no land, I have no garden.  But the middle terrace serves as a sunny spot for some trees in pots, a few plants, and there's space for the herbs I plan to start. The nispero tree gave me a dozen fruit earlier this year, and judging by the flower buds I will get more next year. The lemon tree, planted for my mother as soon as I arrived, is healthy and has three big lemons growing well. The flowering black cherry tree has done nothing - no fruit, no flowers - but I live in hope every year, that the following season something may appear. But the middle terrace serves as a sunny spot for some trees in pots, a few plants, and there's space for the herbs I plan to start. The nispero tree gave me a dozen fruit earlier this year, and judging by the flower buds I will get more next year. The lemon tree, planted for my mother as soon as I arrived, is healthy and has three big lemons growing well. The flowering black cherry tree has done nothing - no fruit, no flowers - but I live in hope every year, that the following season something may appear.

A friend donated the tomato plant, which has so far supplied two or three tomatoes every few days. The two green pepper plants are my greatest success and supply more than I can eat. No point offering them to the neighbours - they have a hundred times as many as I do!

I wrote two years ago about the almond harvest. Last year's was a poor crop, due to the early snow and heavy frosts. This year is better again, and the sacks of sorted almonds go off to become bagged dried fruit (the best quality  nuts) or turrón (the second best quality). Anything classed as third quality (still good!) is kept for the family to use. The older generation joins in with the sorting and the cracking, and it is a privilege to join them and listen to them explaining their traditions and early lives to me, along with arguments about the monarchy and about Catalunyan independence. nuts) or turrón (the second best quality). Anything classed as third quality (still good!) is kept for the family to use. The older generation joins in with the sorting and the cracking, and it is a privilege to join them and listen to them explaining their traditions and early lives to me, along with arguments about the monarchy and about Catalunyan independence.

The almonds are hugely important here - the second most important crop for my neighbours, after the olives. The bad harvest last year hit them hard. It is so easy to forget how the people who grow and tend our food are at the mercy of the weather. Imagine other categories of workers being told they would only get half their salary due to early snow! Meanwhile this week it was announced that police helicopters would protect the mango plantations in the Axarquía region, due to the risk of theft of this valuable crop. I doubt the farmers are insured against theft.

Back on my terrace I am fortunately not dependent on my tomatoes or my nisperos for an income. Now the hot summer is behind us, watering is less critical. I climb the iron staircase each morning after my patio breakfast, and admire those plants that have survived my clumsy tending. The saddest is a pumpkin, which grew rapidly to about six inches in its first fortnight, and since then I swear has been shrinking. Rafa laughed his head off when I showed it to him, asking what was the matter with it. Apparently it needs a couple of square metres of deep earth, not the 6" flowerpot I had left it in! Ah well, I don't like pumpkin much anyway, and only accepted it because I had mixed up calabaza (pumpkin) and calabacin (courgette, which I love). Back on my terrace I am fortunately not dependent on my tomatoes or my nisperos for an income. Now the hot summer is behind us, watering is less critical. I climb the iron staircase each morning after my patio breakfast, and admire those plants that have survived my clumsy tending. The saddest is a pumpkin, which grew rapidly to about six inches in its first fortnight, and since then I swear has been shrinking. Rafa laughed his head off when I showed it to him, asking what was the matter with it. Apparently it needs a couple of square metres of deep earth, not the 6" flowerpot I had left it in! Ah well, I don't like pumpkin much anyway, and only accepted it because I had mixed up calabaza (pumpkin) and calabacin (courgette, which I love).

Meanwhile lunch has consisted of fresh bread, local cheese, and the reddest, tastiest (and, it has to be said, smallest) tomatoes the world has ever known. Delicious! Meanwhile lunch has consisted of fresh bread, local cheese, and the reddest, tastiest (and, it has to be said, smallest) tomatoes the world has ever known. Delicious!

© Tamara Essex 2014 http://www.twocampos.com

THIS WEEK'S LANGUAGE POINT:

Now it's all about practicing for the exam next month. It's annoying - I can argue confidently about the Scottish referendum or about Catalunyan independence. But it turns out I can't describe a photograph as required in the B1 exam. They require that I describe people's hair and style of dress (which has never come up in day-to-day conversation), and I need to be able to identify what can be seen in the top right of a photo. Pointing is apparently not acceptable.

So JuanMi has drilled me in the parts of a photo -

En el primer plano - in the foreground

En segundo plano - I suppose the second layer back!

En la parte superior - in the upper part

En la parte inferior - in the lower part

En la esquina superior derecha - in the upper right hand corner

En el centro - in the middle

En el fondo - in the background

This is all followed by lots of "se puede ver" - one can see; "podemos observar" - we can observe; "me parece que" - it seems to me that; and "A primera vista a mi me parece que la foto representa ..." - At first sight it seems to me that the photo shows ..."

I wonder if, after the exam, I will ever use these phrases again? "La plume de ma tante" springs to mind. Tell me, has anyone every mentioned their aunt’s pen in France? Or described someone with curly hair in the top right corner of a photograph in Spain?

1

Like

Published at 12:33 PM Comments (2)

1

Like

Published at 12:33 PM Comments (2)

119 - Noisy, Noisier, Noisiest

Friday, October 3, 2014

It's over two years now since the sounds outside my bedroom window that very first night, made me think about how we react to noise, especially at night 1 - First Night in My Casita. Back then, in July 2012, I took a firm decision that NOISE, however noisy, was not going to bother me. The combination of dogs barking, children shrieking, adults arguing, and church bells ringing, was clearly going to be a regular occurrence, and even as an inexperienced newbie it seemed to me to be something that I either needed to get used to and push to the back of my mind, or it would grow to become something unbearable.

Since then, someone a couple of streets away has installed a cock which crows triumphantly at 7am, seemingly unaware that we have been awake until the small hours - la madrugada. A house which is quite a distance by road but across the roofs and patios is quite close, has a young goat in a shed on the terrace. And the mule in the parallel street still complains loudly and vociferously whenever he is dragged in through the front door, across the kitchen and out to his stall in the rear yard. The neighbour's children are growing, as is their vocal capacity, and as is the audible frustration of their mother.

This is Spain, and these are the sounds of Spain. The bars keep the television turned up to maximum volume, so the old boy propping up one end of the bar has to shout even louder to join in the conversation at the other end. Often a second television competes, showing a different football match or another noisy game show. In a corner, the clicking of the dominoes is enough to drive you mad if you allow it to. This is Spain, and these are the sounds of Spain. The bars keep the television turned up to maximum volume, so the old boy propping up one end of the bar has to shout even louder to join in the conversation at the other end. Often a second television competes, showing a different football match or another noisy game show. In a corner, the clicking of the dominoes is enough to drive you mad if you allow it to.

There are beautiful sounds as well. The high notes of the pan pipes float down the road, signalling the arrival of the knife-sharpener. The mournful emotional sounds of the agony bells (el toque agónico) as someone approaches or arrives at their death. The annual flamenco competition in the village, the music drifting over the rooftops into my open bedroom windows. The clatter of hooves down the street as the still-working horses head for the fields.

Missing are the sounds that filled my old life. The comforting drone of John Humphrys on Radio 4 in the mornings. Traffic outside the cottage. Aeroplanes overhead. The school playground across the road. Contrary to popular belief, I would suggest that Spain is not noisier. But they are different sounds, and they tend to be at their peak at hours when the UK is falling silent. Not better, not worse, just different.

Yet sadly, the English-language newspapers and the expat forums are full of complaints about noise. Perhaps people imagined that the noises they found charming when visiting Spain on holiday, would somehow disappear if they lived here full-time? Or perhaps holidays in nice hotels on the Costas were inadequate preparation for living in an isolated home in the campo surrounded by working farms and animals? Whatever the reason, "noise" in Spain seems to be a major cause of dissatisfaction. Recently a discussion in a local internet forum included a plea to visitors in nearby holiday rental homes "Can't someone explain to these holiday-makers that some of us have to live here?" The complaint was that visitors were drinking on the terrace and playing music until the small hours. Goodness - how dare they! Just like the Spanish! The behaviour of Spanish children is a regular source of complaints too - "They shouldn't be kept up late like that, it's SO bad for them" is the cry. Perhaps "bad for me" would be more accurate - at least if someone wants to retain UK-style sleep patterns in a country which does things differently. There is a balance to be struck between being blindly uncritical of our adopted country which clearly has faults and problems, and being blindly critical of differences which have emerged naturally from a different climate, culture and history.

It's a noisy country. The cities are modern, vibrant, loud. The rural areas are traditional, sociable, loud. Maybe one day it will change - though I'm not convinced that would be necessarily for the better. In the meantime, we can choose to grump and moan, going to bed at 10pm with ear-plugs and complaining about the children (and adults) shouting outside. Or we can take a kitchen chair out onto the street along with a mug of coffee, and sit comfortably with the neighbours in the cool of the long summer nights, shouting and laughing along with them, until eventually at 2am or thereabouts silence falls, the group of friends bid each other "sueños dulces" and the wooden chairs are carried back indoors.

© Tamara Essex 2014 http://www.twocampos.com

THIS WEEK'S LANGUAGE POINT:

I'm trying to get my head around "falta". Easy enough when the waiter comes over during your meal to check if we have everything we need - "¿Falta algo?" Is anything missing? But then there is "Hace falta ..." which seems to mean the opposite, well sometimes. "Hace falta ...." means "you have to", a bit like "tiene que" but less personal.

So we can imagine the following conversation ...

"¿Falta algo para la paella?" "¿Falta algo para la paella?"

"Si, falta un pimiento rojo."

"Vale, hace falta comprar uno."

"Have we got everything for the paella?"

"No, we are missing a red pepper."

"Right, you have to buy one then."

This is a great example of just having to go with the flow. A direct word-by-word translation of that conversation would render it ridiculous.

"Anything is missing for the paella?"

"Yes, a red pepper is missing."

"Right, it makes missing to buy one."

And for months, whenever I heard "hace falta" my English brain tried to grapple with the concept of "hace" (it does, or it makes) and "falta" (missing), together meaning that you have to do something. Finally, with the help of my unofficial language guides, I have been persuaded to allow my English brain to close down, and simply accept that translating doesn't work. You have to hear it, and you have to say it, without translating. “Hace falta escucharlo, y hace falta decirlo, sin traducirlo.”

2

Like

Published at 7:40 AM Comments (4)

2

Like

Published at 7:40 AM Comments (4)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|