Vineyard visit at Bodegas Ramos-Paul - A hidden treasure in the Serranía de Ronda

Tuesday, January 27, 2026

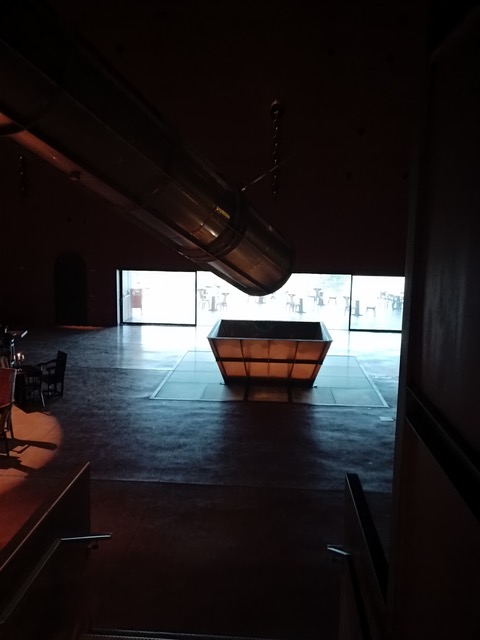

The 150-meter tunnel where Ramos Paul wines are aged. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Most people come to Spain for the climate, culture, nature, and, not least, food and wine. One activity that combines all these elements is a visit to a bodega. Winemaking requires open plains and sunny hillsides, often set against beautiful natural surroundings. At the same time, it is a tradition-bound process deeply rooted in the country’s history, culture, and gastronomy.

The province of Málaga has many commendable bodegas, and today we visit Ramos-Paul in the Serranía de Ronda. At this unique bodega, the wine cellar is a tunnel dug into the mountain itself, and the tour does not include the usual tasting of last year’s wine, but a vintage from 2006! If you are a wine lover, winter is a lovely time to visit, when the hosts light the fire and invite you into their cosy kitchen for an intimate meal, exquisite wine, and a fascinating story.

Beneath is a Roman theatre

The view of the bodega from Acinipo. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The first time I saw the bodega was from above. We visited the ruins of the 2,000-year-old Roman legionary city of Acinipo, located on a mountain plateau between Ronda and Setenil de las Bodegas. From the cliff edge, you have an incredible view of the Andalusian mountain landscape, and far below us, we could see a bodega with vines in the most beautiful autumn colours. We must go there one day, I said.

Bodegas Ramos-Paul produces wine at around 1,000 metres’ altitude in the renowned DO region of Serranía de Ronda. Here, the exceptional location and microclimate favour both grape growing and wine ripening. No matter the season, it is a sight that takes your breath away. The estate itself has a spectacular location facing the Sierra de Grazalema. True to its surroundings, the place appears to have been here for centuries, even though wine production began in 1999 and the bodega, inspired by both Roman and classic Andalusian architectural styles, was completed in 2006.

Welcome. Photo © Karethe Linaae

On the steps of the beautiful finca, the owners, the couple Nané Ramos-Paul Ruano (57) and Pilar Martínez-Mejías Laffitte (56), are waiting. Every season is busy at the winery. In addition to tending the grapes and producing wine, they offer private tours for small groups around the vineyard. The day before we arrived, they had also had an English commercial film crew on site, who had recreated a Tuscan vineyard in a few hours.

Today, they are also expecting guests, so we head into the kitchen. Nané cuts lomo ibérico and goat cheese for the wine tasting, and Pilar makes coffee while we chat – because the unique thing about this bodega is that the hosts do everything themselves. Today, their daughter, the 27-year-old Inés, is also home from Marbella to assist.

Inés, Nané and Pilar at Bodegas Ramos-Paul. Photo © Karethe Linaae

– Our guests usually find us through recommendations. They know that they are getting a different experience, because this is both our home and our business, says Pilar. – Here they can enjoy the kitchen, the lounge or the terrace, while also getting a personal experience. Many appreciate the added value of us serving them ourselves and sitting at the table with them and telling our story.

The legacy that became a passion

Classic style. Photo © Bodegas Ramos-Paul

The history of the winery began as an inheritance. In the time of Nané's grandfather, the family owned the entire 850-hectare valley. When the property was divided between his seven children, one piece of land went to the eldest grandson, Nané. That is why the bodega bears the name Ramos-Paul, his grandfather's surname.

Pilar's roots lie in beer, not wine. Her mother is a cousin of the Osborne family in Jerez. Over a hundred years ago, two of the brothers started the family business, Cruzcampo. The brewery was sold to Guinness and later Heineken, which is the current owner. When Pilar received the inheritance from her grandmother, she and Nané decided to create this project together.

– When we arrived here, there was absolutely nothing. But in 1999, we were younger and had more energy, so we took over the land, planted and built everything from scratch, recalls Pilar.

– Inés was only eighteen months old when we started. We dropped her off at school at 9.00, then went here to follow the work and picked her up again at 17.30 - every day. When she started university, we realised that this was our life now, so we moved here.

Building a bodega on a cliff, with a Roman theatre of great conservation value, was a demanding process. The authorities had already expropriated the ruins of Acinipo in 1974 and assumed responsibility for preserving the site.

«It’s actually more of a lifestyle than a business, because our philosophy is about time». Photo © Bodegas Ramos-Paul

– However, the ruins are still on the family property, because they are not something you can just move, jokes Nané, and continues: – We got a special building permit because our project was declared of public and social interest for Ronda. That also made the approval of the tunnel easier. The only condition was that we had to have an archaeologist employed during the entire construction period to check for any discoveries. The tunnelling work lasted one year, three months and 24 hours. Everything had to be done by hand, that is, with a hammer, chisel and impact drill.

«The tunnelling work lasted one year, three months and 24 hours. Everything had to be done by hand, with a hammer, chisel and impact drill». Photo © Karethe Linaae

No experience in the industry

When they started, Pilar worked as a veterinarian, and Nané worked in the financial markets with Morgan Stanley.

– They were jobs we did but didn’t love, he admits. – Then this opportunity came along, and some coincidences fell into place, and here we are. We started from scratch, with no knowledge. A close friend, who is an excellent wine consultant, helped us immensely. He was the CEO of two of Spain’s most famous bodegas, Marqués de Murrieta and Castillo de Ygay, for 30 years. After many years here, we have obviously learned an incredible amount thanks to him.

– The bodega is more of a lifestyle than a business, because our philosophy is about time, adds Pilar. – Twenty-five years is young for a bodega. We are the first generation, and projects like this often take several generations before you see the light at the end of the tunnel. We intend that the next generation take over one day.

Terrace with a view. Photo © Bodegas Ramos-Paul

Inés is an architect in Marbella, but as an only child, she knows that one day the bodega will be her responsibility. She is the designer for the family’s future project on the neighbouring plot, which also belongs to the family. There, they plan to grow more vines and build a hotel with 15 rooms.

– My dream is to start my studio up here and work on both, says Inés. – This is a beautiful business, and since I grew up here, I would love to be able to make a living from it.

The hotel idea came from their customers, who have often expressed a desire for accommodation. Some come in their own car, others by minibus or taxi, but what they all have in common is that they visit a bodega where most people consume alcohol.

– Many ask Oh, dear, don’t you have rooms we can rent so we can stay here? We must simply apologise and explain that we must finish this project first, before starting the next one, Pilar says.

The plan is to expand the bodega with the boutique hotel, allowing guests to finish their meal and go straight to their room.

– We are in a somewhat remote location, and that is something I love.

Respect for tradition and quality

View towards Sierra de Grazalema. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Bodegas Ramos-Paul's philosophy is minimal intervention. The winery primarily grows four grape varieties: Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Merlot. The grapes are harvested by hand, so only the finest fruit is selected.

– This year we produced 50,000 bottles, while in an exceptional year, we can reach up to 125,000. However, the quality this year is brilliant, so 2025 could be a fantastic vintage, Pilar promises.

This year's wine will neither be on the market nor available for wine tastings at the bodega for many years. If I calculate correctly, we will probably have to wait around 15 years before we can taste it!

– We prefer to wait two winters before we put the wine in barrels, so that the cold does its job with a natural clarification, explains Nané. – And for every year in barrels, our wines are in bottles for about twice as long. So, if they spend, let’s say, four years in the barrel, they will spend at least eight years in the bottle before reaching the market. Bottle maturation is as important to us as the time in the barrel itself.

The quality comes from their terroir. The vineyard is located about 20 km from the Strait of Gibraltar and benefits from a special microclimate, rich soil and the region’s generous rainfall. This is probably why the Ramos-Paul wines have been awarded 91 and 92 points by the renowned wine critic Robert Parker, making them competitive with wines from Bordeaux, California and South Africa. The wine, which is ideal for long bottle ageing, is now available in 21 countries, including the USA, Russia, Singapore, Canada, Mexico and several European countries.

– All the information about the climate is in the grape skin – how much it has rained, how strong the wind has been, the heat and the cold, Pilar explains enthusiastically. – Not all soil types and climates are suitable for growing grapes, but our microclimate makes us truly unique. The most important factor in capturing all this complexity is the temperature difference between day and night: the warmth of the day helps the grapes ripen, while the summer nights are often cool, between 14 and 18 °C. Each grape variety develops differently under these conditions, which is why our wines are never exactly the same – each variety is its own little world.

Nané during la vendímia.«Old wines create the framework for nuances you will never find in a young wine». Photo © Bodegas Ramos-Paul

The winery’s barrel ageing also varies from year to year; each vintage is unique and treated accordingly. What is not used in their blended vintage wine, Ramos Paul, goes into the BM line – a single grape wine.

– We don’t care about labels, says Pilar. – When you have a microclimate like ours and grapes that come straight from the field, with no additives, isn’t that the most natural thing to do? Our advisor always reminds us that wine is made in the vineyard – and that it can be ruined in the cellar if you’re not careful.

Today, a well-equipped laboratory and a skilled oenologist can do a lot, but these wines often don’t respect their surroundings in the same way and are more laboratory driven. So, what does it take for a wine to be truly exquisite, I ask.

– Primarily, time, Nané points out, adding that it’s something that’s often overlooked today. – We prefer vintages from 2010 and earlier. I know they are more expensive, but there are also affordable vintage wines that offer qualities you never get in a young wine. Old wines set the stage for nuances. They are like time capsules.

Young wines can be fruity and marked, with a clear linear structure, but depth is rarely found, he explains. When you taste wines that are 15–20 years old and still alive and developing, it is almost impossible to discover the same in a young wine. That is why Nané distinguishes between a good wine and a great wine.

– A young wine can be very good, but never great. A great wine, on the other hand, will always be old.

Award-winning wines

Pilar with Ramos-Paul vintage wines.«A very famous wine taster once said about our 2006 and 2005 vintages: Brad Pitt and George Clooney – take your pick!» Photo © Bodegas Ramos-Paul

It’s only about half an hour until the guests arrive for lunch. The hosts invite us for a quick tour of the wine cellar, which is located down a few stairs and starts under the house. It’s not our first visit here, but it’s always a magical experience. The tunnel, dug by specialist miners from the Czech Republic, winds in a long U-shape, more than 150 meters into the mountain.

As we stand among the French oak barrels, I can’t help but ask which of their wines is the ‘best’ one.

– We get that question a lot, says Nané with a twinkle in his eye. – I always answer with a counter-question: How many children do you have – and which is ‘best’? No one dares to answer that. A very famous wine taster once said of our 2006 and 2005 vintages: Brad Pitt and George Clooney – take your pick!

Bodegas Ramos-Paul. Photo © Karethe Linaae

3

Like

Published at 5:10 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 5:10 PM Comments (0)

Whatever lies ahead …

Wednesday, December 31, 2025

January is the month of new beginnings. It’s also a time for self-examination, self-renewal, self-blame and maybe even a little self-flagellation. And while we usually give up on trying to create a ‘new me’ by February 1st, we continue to make the same resolutions year after year.

The most important New Year’s resolutions for Spaniards include exercising more, eating healthier, losing weight, saving money, spending more time with family, learning something new and quitting smoking or cutting down on alcohol. These reflect universal desires for better health and personal development. Still, if one looks more closely at what people really want, I think it’s about being content and at peace with oneself, in mind and body.

Happiness – yes.

Joy – definitely.

But perhaps most of all, contentment.

According to experts, those who search for happiness should wake up every morning with a purpose and end each day with gratitude. This is good general advice, but happiness is a fleeting concept. Like joy, it is a feeling that does not endure. Perhaps that is why it is described as a rush of happiness.

Contentment, on the other hand, is a more stable state of mind. It is a somewhat old-fashioned expression, mostly used by people of a certain age, like myself. That does not make it any less universal. Contentment can be defined as a persistent feeling that one’s needs, desires or goals are being fulfilled, often accompanied by acceptance and inner peace. It does not suggest a passive acceptance of everything that comes our way, nor an end to self-improvement.

Perhaps that is what Aristotle meant when he described eudaimonia as the highest human good - the ultimate aim of life that is desirable for its own sake and not for the sake of anything else. Because isn’t that what we all want – whether we have an extra kilo or a wrinkle or that fancy sports car, or not?

Whatever the new year brings, meet it with openness, wonder and gratitude. None of us can be in a permanent state of bliss. It is only in fairy tales that people live happily ever after.

5

Like

Published at 5:00 PM Comments (1)

5

Like

Published at 5:00 PM Comments (1)

The Summer That Never Ended

Thursday, November 6, 2025

Summer heat all year. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2025 has been the year when summer refused to end.

Every day in June, the temperature climbed above 30 degrees here in southern Spain. Then came the Terral winds, bringing the tropical heat of July and August, with new records for both highs and lows. That much was expected. What wasn’t expected was that the heat would linger well into autumn, with tropical nights on the Costa del Sol even in mid-October.

Playa. Photo © Karethe Linaae

People now say it isn’t that bad, as we have had worse summers — but I disagree. In the summer of 2025, we were 2,8 degrees above the normal temperature average for the past 35 years. At the same time, it’s unsettling when what used to be two months of summer stretches into more than four. And all of this has happened within the space of just a decade.

Cracked earth. Photo © Karethe Linaae

We were lucky this year. After yet another dry winter, the long-awaited rain finally arrived at the end of March. Without that vital downpour, the Costa del Sol’s summer would have looked very different. Thanks to the rain, the authorities could lift most water restrictions, allowing Málaga province’s 75,000 swimming pools to refill, six million tourists to feast on freshly laundered towels, and even the beach showers to work again in most coastal towns.

Fountain, Marbella. Photo © Karethe Linaae

By 30 September, the end of the hydrological year, our water reserves were almost three times higher than in 2024 — and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. But the cooler temperatures and rain that usually signal autumn didn’t arrive until the final week of October. And when they did, the skies opened. It seems the new meteorological rule is all or nothing. Needless to say, there’s barely a drop in the forecast for the rest of November.

Rusty fall. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I can honestly say that not since my winter in Los Angeles have I longed so deeply for cool air, fresh winds, thick jumpers — and above all, rain. That’s what autumn should be: a time to recharge, both hydrologically and psychologically, before the next long summer.

Something is brewing. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Now that it’s finally a little cooler and wetter, we must resist the urge to swap complaints about the heat for grumbling about the cold. Instead, let’s welcome whatever the season gives us — the wind, the rain, the storms. It’s time to get cosy again.

Please, I want to go home! Photo © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 2:46 PM Comments (2)

4

Like

Published at 2:46 PM Comments (2)

With a wheelchair on the moving truck

Friday, October 31, 2025

Geir. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Most people who move to Spain have their own requirements. According to real estate agents on the Costa del Sol, most people desire a south-facing terrace, ideally with mountain and sea views, proximity to downtown shops and restaurants, and, preferably, also within walking distance of the beach. But when you are in a wheelchair and dependent on extra oxygen, the requirements are completely different. Flat ground, wide sidewalks, and proximity to health facilities become essential.

New challenges

Geir and Anne-Grete, happy in Spain, October 2025. Photo © Karethe Linaae

She was a chef and head librarian from a fjord in Western Norway, and he was the secretary of the Transport Workers' Union. Both had been married before and had children of their own. However, in 2008, coincidences and an audio library for professional drivers on Highway E-3 brought Anne-Grete Bjørlo (69) and Geir Kvam (68) together. Eventually, their relationship became more than just audiobooks. Geir proposed in Italy in 2010, but before they had married, they got a ‘third wheel’ on the wagon – Geir's illness, severe, genetically determined emphysema.

Winters are tough in Norway, and even as both were still full-time employed, the couple began toying with the idea of moving south. The plans were put on hold during the pandemic, but in 2023, when they both retired, they took the plunge and decided to move to Spain.

All of us who have chosen to live in the South have our challenges. Life as a foreigner in a foreign country can bring its trials. Many experience communication problems, legal challenges, fear of being ripped off in real estate negotiations, or even a feeling of social isolation. In addition, recent years have brought new concerns with record temperatures and water shortages. My personal challenges when moving were learning the language, getting a Spanish driver’s license, buying a house and vehicle while trying to integrate into the local community, and making Spanish friends. It wasn’t always easy, but everything is relative.

Geir and Anne-Grete’s move brought a completely different set of challenges than most foreigners experience. Geir is in a wheelchair and depends on a regular oxygen supply, while Anne-Grete is his right hand in everything, every day. Many towns and villages in the Málaga Province were therefore out of the question for the couple. Picturesque alleys, beautiful cobblestone streets, buildings on steep slopes, winding sidewalks along flower-adorned walls that suddenly end in a high curb or steps, and pedestrian crossings without lights or ramps may not be a problem for most people who move down here. But what about when you can't walk on your own and have only 20% of your lung capacity?

A happy coincidence

Anne-Grete and Geir on the beach promenade in Torre del Mar. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Finding what was to be their Spanish hometown happened by coincidence. Geir was training his legs on the treadmill at home in Oslo when the TV was showing a documentary about the Costa del Sol. First up was the town of Nerja, a lovely coastal city that they had visited, but which wasn’t very wheelchair friendly. The next part of the series was about a town they didn’t know - Torre del Mar in the municipality of Vélez-Málaga, also on the eastern Costa del Sol.

- Seeing the downtown area in the video, I thought, «Wow, that’s flat. I could live there!" The city appeared, for the most part, to have wide sidewalks and a pedestrian street that led down to the beach promenade. The entire centre seemed very accessible, which would mean that I could get out every day. If we were to remain in Oslo, I might have got out a couple of times each winter, Geir explains.

Anne-Gretes first reaction was that Torre del Mar was “just a bunch of boring low-rise buildings”, but when they explored it on Google Maps, she understood Geir’s point. They started circling areas on the map that had everything they needed within ‘wheeling’ distance. When they later searched for rental properties online, an apartment popped up. It was large, and the location was perfect. Using Google Translate and WhatsApp, they got in touch with the agent, who reserved the apartment.

- I flew down and brought Geir with me via video, and he just said, 'Go for it!' The next day, I signed a long-term rental contract, and now we have the world's loveliest Spanish family as landlords, exclaims Anne-Grete.

- Everything we need is within reach. The nearest hospital is right up the hill, I can roll to the medical centre in two minutes and do the shopping on my way home, adds Geir.

While many of the holiday apartments in the town are only intended for summer use, their flat is usable for year-round living. Yet, they noted significant differences between the building codes in Scandinavia and Spain. Sound insulation, for instance, can be rather poor, but that is part of life here.

- The electricity was a challenge, especially for me, who loves to cook. When I used the oven, I couldn’t use the hotplates at the same time, recalls Anne-Grete.

But she moved the old gas stove out onto the veranda and arranged an outdoor kitchen there, which now doubles as an extended living room in the summer. Later, the owners upgraded the electricity, so their time of frequent blackouts is over.

Immigration and bureaucracy

At home during the first winter. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Anne-Grete and Geir agree that the move was a big job. It was necessary to deal with the health and tax authorities in Norway, while a similar process awaited them in Spain.

- I tried to arrange a lot before Geir came down, but it took time to get NIE, a Spanish bank account and a mobile phone, which are absolutely necessary," warns Anne-Grete.

Residencia and Seguridad Social papers also came into place, and they had an accountant help with the Spanish tax return.

- In Norway, we were told that we’d have to pay tax there for the first three years, which turned out to be wrong. For 2024, our pensions were first taxed in Norway and later in Spain. Residents must pay tax in the country where they live, so proving Spanish residency became another hurdle in an already time-consuming process. Now that it’s finally sorted, next year will be easier! Just ensure that your electric bill is in your name — it’s proof of residency for the tax authorities, according to Anne-Grete.

Other things went more smoothly. When they brought their car from Norway, some new Spanish friends helped them rent handicap parking nearby for half the price they would have paid in Oslo.

The Spanish healthcare system, however, was more cumbersome than what they were used to back home. Blood test results that used to arrive within minutes in Oslo took a couple of weeks the first time, but with the help of their Spanish interpreter, they managed to streamline the process.

- You cannot fight the system, so you must figure out how to work best with it, says Geir, who is intimately acquainted with doctors.

Through the Spanish social security system, they now have free GP services and specialist services (pulmonologist in Geir’s case) and access to subsidised medication.

- It is vital to have a professional interpreter with you who knows the healthcare system if you have health challenges, not just a random person who knows a little Spanish, Geir points out.

An ordinary town for ordinary people

In Torre del Mar. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The Norwegian couple calls Torre del Mar “an ordinary town for ordinary people.” Their neighbourhood mostly consists of local Spaniards, both retirees and ordinary workers, while the city’s holiday apartments are mostly closer to the beach.

- The neighbours are very nice, says Anne-Grete. They open the front door for us and ask how Geir is if they haven’t seen him for a while. On our first Christmas Eve, the electricity went out, and the automatic fuse didn’t respond. The neighbours came over and helped us fix the problem. If there is anything, they’ll help.

Geir adds that people will even move chairs so that he can enter a restaurant or a café with his wheelchair.

- There's a lot more warmth in the way they do things. And they don't help because they have to, but just because that's how they are.

They have both found their daily routines in Torre del Mar. In the morning, Anne-Grete goes to the allotment garden she leases, a 20-minute stroll away.

- I also do the cooking. For me, cooking and buying ingredients is half the charm of living here. We have also built up a social circle with both Spanish and international friends. The conversation is a mixture of English and Spanish, with a little help from Google.

As for Geir, he often has periods with less than 20% of his normal lung capacity, so it takes a couple of hours to get his body going.

- I try to get out every day, although it must be planned. Otherwise, I write a little and play music on my own, and, if possible, I take my Fender to a jam session at a café down the street one evening a week.

Both started taking Spanish classes, but with all the paperwork and Geir’s health issues, they have put them on hold for now.

- The goal for me is to be able to master everyday conversations and be able to read books in Spanish, declares Anne-Grete, who learns a lot from the other hortelanos at the allotment garden, where she is the only foreigner.

- Grammar is the big problem. Now I understand why many foreigners in Norway struggle with grammar. It's not easy!

Geir often refers to Google and notices that when they try speaking in their stumbling Spanish, the locals seem happy that they are trying.

- That's really the best thing about our town – it is a very inclusive and still mainly Spanish coastal town.

No regrets

On the beach promenade during their first year in Torre del Mar. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Neither Anne-Grete nor Geir regret their decision to move for a second, and they are more than willing to share advice with others who plan to do the same:

- It’s never too late to make new choices — just think about what kind of life you want moving forward. If you can, start with a six-month stay, especially during the winter, when you get the most bang for your buck down here. And finally, use a broker and arrange everything in advance, is Anne-Grete’s advice.

- If we are going to live in Spain, it is our duty to adopt and learn how things are done here. What we think about the system is irrelevant, says Geir, who dealt with many bureaucrats in his former position.

- We cannot expect the Spanish health care, banks or road services to be the way we are used to. Be polite. Bureaucrats have a certain status here, but if one meets them with humility and a bit of humour, things will move ahead. After our third visit, we were already on greeting terms with the funcionarios in the town hall."

The freedom of public transportation

On a trip to Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

This fall, Geir agreed to sell their car. It was a tough, but necessary, decision for the former truck driver. At the same time, they have begun to travel again, taking the train to Madrid (to renew a passport) and the bus to Ronda. They cannot be more pleased with the help and assistance they got wherever they went.

With Geir’s condition, they will always need a hand, as it is not only about mobility but also about oxygen. Geir sometimes has as low as 17% of his normal breathing capacity.

- If you completely tape your mouth and one nostril shut and then take the thinnest straw you can find and tape it to the other nostril, then you are where I am, he explains.

His reality certainly knocks out all my so-called challenges and will make me think twice before the next time I sulk about some public road works that never get finished or a neighbour who is a little too fond of late-night Flamenco serenades.

After almost two years on the Costa del Sol, they still agree that they found their dream location in Torre del Mar. Although life can be challenging, neither of them regrets moving to Spain – not for a second!

It is both inspiring and humbling to spend time with Anne-Grete and Geir and observe them in their everyday life. They have found a perfect ‘nest’ within rolling distance to everything they need and a neighbourhood that hardly has any foreigners. Geir’s life is a constant battle with lung infections and ‘refills’ of blood plaques. I cannot help but admire their positive, yet realistic, attitude.

- It was never our goal to climb Mount Everest, so we preferred to go to Spain. We focus on what we can do instead of what we can't, and this has given us many great experiences.

Strolling and rolling along. Photo © Karethe Linaae

5

Like

Published at 5:32 PM Comments (1)

5

Like

Published at 5:32 PM Comments (1)

PLAN INFOCA - Andalucía's Regional Forest Fire Service

Tuesday, October 21, 2025

Forest fire unit with Isa as only female member. Photo © Isa Moreno-INFOCA

Climate change is causing increasingly extreme meteorological phenomena, including heatwaves, intense storms, and prolonged droughts. These are things that we who reside in Andalucía must learn to live with, but there is one consequence of climate change that may threaten people and the natural environment more than anything else.

In recent years, the frequency and spread of forest fires have increased significantly. Canada's almost uncontainable fires have brought airborne ash all the way to Europe, but forest fires at home have also become more difficult to control. I met an admirable couple who work for the Andalusian Forest Fire Service in western Málaga. Isabel María Moreno Jiménez (52) and José del Río González (54), known as Isa and Pepe among friends, fight and prevent forest fires and other natural disasters – she as the agency's emergency manager and he as the technical manager for fire operations. I joined them at work and learned about the emergency plan and the many challenges that today's forest firefighters face.

Forest firefighters Isabel María Moreno Jiménez and José del Río González. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The historic Sierra Bermeja fire

Wednesday, September 8, 2021. It's almost 10 p.m., and Isa and Pepe have just sat down to eat dinner when the alarm goes off about a wildfire in the Sierra Bermeja near Estepona. Within a few minutes, both are on their way, fully equipped with firefighting gear, Pepe in the Infoca jeep on radio contact with the provincial operations centre in Málaga and Isa with her unit. As they approach the scene of the fire, a sea of flames can be seen against the night sky.

“At night, when we can’t fly, the firefighting work is done with the help of ground crews with fire hoses and powerful all-terrain vehicles that can manoeuvre in steep terrain.” Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

No one knew at the time that this fire would destroy 8,401 hectares of forest and take the life of a firefighter, making it one of the worst fires in the history of the Málaga province. Despite a crew of several thousand working around the clock, the flames spread to seven municipalities in the province – Estepona, Casares, Jubrique, Genalguacil, Júzcar, Faraján and Benahavís – where 2,670 people were evacuated. The fire raged for six days before it was declared "under control", but work continued for a full 46 days before the forest fire was officially extinguished.

What is PLAN INFOCA

Forest fire operation with a helicopter. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

Andalusia's regional forest fire management plan, Plan Infoca, has been in operation since 1985 and includes measures and systems that prevent and extinguish forest fires and restore affected areas.

In 2025, the plan has mobilised the largest unit in the region’s history with a budget of €257 million, 43.2% to extinguishing work and 56.8% to prevention. To guarantee maximum coverage and rapid response, this includes over 4,700 professionals, a regional operations centre, eight provincial operations centres, 23 forest defence centres, ten sub-centres, three specialised brigade bases, 186 guardhouses, 40 aircraft, 28 helipads, eleven airstrips, 1,011 vehicles, 119 forest fire engines and 2,200 open water tanks.

From midwife to firefighter

Forest firefighters Isabel María Moreno Jiménez and José del Río González. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Neither Isa nor Pepe planned to work in firefighting, but chance brought them together, and since then, the rescue service has been their second home.

“I wanted to be a technical draftsman when I was young,” Pepe admits. “But after terminating my studies and working for a year, I missed being outside in nature. I’ve always liked hiking in the mountains, so instead of continuing with architecture, I decided to become a forestry engineer and took a course to change my field of study.”

“My family has always worked in forestry and agriculture, but my childhood dream was to become a midwife, Isa recalls. “I needed points to get into the program and had to take some extra courses, and that’s where I met Pepe. I changed my plans and started studying forestry engineering, because it covers a wide range of topics and allows you to work with many different things.”

After graduating, both applied to Infoca in their hometown of Ronda. However, since they lacked work experience, they ended up working for two years as firefighters in Toledo and one year at a helicopter base before finally getting a job at the Forest Defence Centre (CEDEFO) in Ronda in 2004.

Isa started as a fire specialist, but a few months later, she got pregnant.

“Both of us couldn't continue working in this field with small children, so I left it until the children were older. In 2019, Infoca needed staff and contacted me. I passed the tests, got a couple of longer vacancies and was offered a permanent job last autumn. In my current position, I am responsible for the rural monitoring huts in our area and the logistics during emergencies. At the same time, I oversee fire studies where we take samples of vegetation to measure humidity and determine the flammability of a specific area.”

Isa at work. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

Pepe is one of three operations technicians responsible for the forest fire unit in Ronda, leading the extinguishing work in western Málaga. They work in continuous shifts where one has time off, one is on 24-hour duty, and one is ready by the helicopter in case of an emergency call.

Pepe in the helicopter. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

“When a fire breaks out in our area, my job as a technical officer is to decide which resources need to be allocated to each emergency. If the fire spreads and we must call in units from other areas, the operations centre in Málaga takes over. The helicopter drops me and my team off at the fire so I can assess the situation. At the same time, we have a technical officer in the air who decides where to drop water. The work is a joint effort – the ground crew can't do anything without water, and the air resources need the teams on the ground to work the terrain and put out the flames.”

Not a job for everyone

Back to the helicopter. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

Most firefighters have a background in agriculture or forestry. However, the vital thing, according to Isa and Pepe, is that they understand the seriousness of the job, are strong both physically and mentally, and are not intimidated.

Isa is not anxious at work, but can understand that some people become overwhelmed when they face a forest fire for the first time. “A colleague was completely paralysed with fear during the Sierra Bermeja fire. He had worked in the forest fire service for a couple of years but had probably never experienced anything like it”, she recalls.

Pepe is never afraid, whether in the air or on the ground

“What worries me is the responsibility I have for the units. Infoca's safety apparatus works very well, but no one can control nature. The ground crews generally only work on the flanks and on the leeward side of the fire, but what if the wind suddenly changes, surrounding the unit with flames?” he wonders.

“I understand that people want to help, but specialists are needed to put out forest fires.” Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

Working in the forest fire service is not for everyone. Few women enter the profession, and Isa is still the only female firefighter at the Ronda operations centre. But things are changing. The city now has a higher education program for rescue services, and more young people wish to work in the rescue unit and do their internship with Infoca.

When there was a fire in the past, the fire brigade would go out to the Andalusian villages and bring people to work, but today, special education, training and entrance exams are required.

“We are the only emergency service where the requirements are the same for men and women, which includes physical and psychotechnical tests”, Isa points out.

Permanent employees are evaluated annually, and if they fail the requirements, they get a warning. Under normal circumstances, more senior employees are eventually transferred to less physically demanding positions, such as watchmen or drivers.

Infoca’s work does not only pertain to forest fires anymore. Last year, the Andalusian Agency for Security and Comprehensive Crisis Management, EMA, was established. This includes all the structures for civil protection in emergencies and covers all types of natural disasters and emergencies, such as floods and search and rescue. Infoca was therefore active during the Valencia flood disaster of 2024 and sent weekly convoys to the affected areas.

A day on the Infoca base

Infoca’s operations centre in Ronda is located in a guarded area outside the city and is one of the largest and most well-equipped centres in Andalusia.

“Each Andalusian province has two or three forest protection centres, depending on the size of the forest. Málaga has two, one in Ronda and one in Colmenar, northeast of Málaga city”, Pepe says.

The centre in Ronda covers over 30 municipalities from the Serranía de Ronda to the Costa del Sol. They have access to 21 units, each containing a crew of seven professionals, in addition to vehicles and equipment. The centre has people on call 24 hours a day, and when a fire is reported, the units must be inside the helicopter within ten minutes. Infoca can also send us to forest fires outside the region or even abroad.

Isa and Pepe at work. Photo © Isa Moreno

The centre of the base is a huge helipad where a bright yellow helicopter is ready to take off. Next to the helipad is a pool - or ‘dip site’- where the helicopters fly in and fill their slings (called Bami-buckets), which can hold up to 1,300 litres of water. A couple of tanks ensure that the helicopters never run out of fuel, and a mechanic checks the engines on these warhorses daily.

Pepe explains: “The aircraft used in the firefighting work depends on the circumstances. The Fokker planes that collect water from the sea and lakes can carry up to 5,500 litres of water, but they cannot be manoeuvred in the same way as helicopters. Planes are often used at the front of the fire, while helicopters work along the flanks and in more difficult-to-reach zones. We also use smaller planes in which a red, flame-retardant compound is added to the water. This impregnates the vegetation and indicates to the ground crews and other planes where they have sprayed.”

The sun is starting to set, which means that helicopters and planes cannot be used until the next morning. Two of the operations centre's pleasant helicopter pilots, one from Bolivia and one from Portugal, are therefore going home.

«Helicopters are only used when the fire has been checked, and it is confirmed that aircraft are needed”, Pepe informs me and continues: “In Canada, where the forest is huge, air patrols are used to detect fires, but we do not have such large areas, so we utilise a surveillance network with guard cabins. Helicopters are also very costly to have in the air, and if we fly around looking for fires, we risk not being able to fly when we really need to, as the pilots can only fly for two hours before they must take a 20-minute break. We also use drones to pinpoint the perimeter and detect flammable areas using infrared radiation, as long as they don’t interfere with other aircraft. At night, when they cannot fly, the extinguishing work is done using ground crews with fire hoses and powerful all-terrain vehicles that can manoeuvre in steep terrain.”

“Actually, we get a lot of extinguishing work done at night, because the temperature drops and the humidity increases. At the same time, we can more easily see where the flames are”, Isa admits.

Causes and development of fires

“In the past, more fires were started deliberately, especially by developers wanting to build in forest areas — but the law has fortunately changed.” Forest fire by Highway AP-7 near Costa del Sol. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

On high-risk days, a fire will likely break out somewhere in the western province of Málaga, especially on the Costa del Sol, which is drier, more populated, and has more housing and motorways that can lead to forest fires.

«Irresponsible actions and negligence cause most fires”, Pepe states.

During seasons with high forest fire risk, bonfires, barbecues, and burning in agriculture and the use of motorised machinery in forest areas are prohibited. These can create a spark, and that can be enough.

Infoca's forest fire investigation brigade can pinpoint exactly where a fire has started, but often does not know how or why.

“Unlike cigarette butts, broken glass or a lightning strike, no evidence is left behind if a fire is started with a lighter. When we were working in Toledo, the environmental agent showed us the starting point of a fire where we could see a perfectly burnt match!” Isa remembers and explains: “In the past, many fires were started, especially by developers who wanted to build in forested areas, but the law has fortunately changed. Even completely burnt-down forest areas cannot be rezoned for at least ten years. The law also prohibits the use of burnt material, so that no one burns forests for that reason anymore. Fire debris is left behind so nature can regenerate. Only in the case of exceptionally large forest fires does the Junta de Andalucía put them up for public auction as part of a reconstruction plan for the destroyed area.”

Forest fires have a diurnal cycle, with the greatest risk of igniting during the hottest part of the day. At the same time, climate change, with longer summers and shorter winters, has extended the forest fire season.

“I am not anxious at work, but I understand how overwhelming a forest fire can be the first time someone faces it.” . Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

But the climate is not the only reason why forest fires are more severe today.

“In the past, people used the forest and brought fallen branches as firewood. Farm animals were taken to summer pastures in the mountains where they ate the undergrowth under the trees that now grow wild and can ‘feed’ fires. We have huge, abandoned forest areas. One of the few exceptions is the cork forests of Andalucía, where the surrounding vegetation is kept under control due to the harvesting of cork. As a result, these areas have fewer forest fires”, says Pepe, who regrets that the forestry is usually no longer enough for a family to live on, and everything requires permits. The authorities have initiated certain measures, such as subsidies for sheep and goat farmers who let their animals graze and keep the firebreaks clean. Otherwise, they grow back very quickly.

“In the winter, we do preventive work, such as maintaining firebreaks. It is almost impossible for a firebreak to stop the flames of a crown fire. But if the fire is moving slowly, they are very effective. They are also an escape zone for the fire crew and a safer place for us to work”, says Isa.

The best help is to stay away

“Irresponsible actions and negligence cause most fires.” Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

As professionals in the fire service, Isa and Pepe are grateful that people want to help in a forest fire, but their advice is clear: if you see a fire, call 112 and get away as quickly as possible.

“The problem today is that everyone calls 112 for every little cloud of smoke”, Isa regrets.

The emergency services receive endless calls from the San Pedro road, where the ‘fires’ often turn out to be people burning chestnut shells, because Andalusian farmers burn plant waste in the autumn

“The 112 service has taken us a big step forward, but Infoca must always confirm whether there is a fire”, Pepe says. He sends the nearest unit with an emergency vehicle, and if it is a small fire, the ground crew or the local fire department can put it out. But if there is the slightest doubt, they go out in the helicopter.

4×4 vehicle with equipment for each ground unit. Photo © Isa Moreno/INFOCA

A significant problem for forest firefighters is that people often park their vehicles near fires to see “what’s going on”, which can make it difficult for emergency vehicles to get through. However, it’s not just people who come to look and take pictures that can cause problems in these emergencies.

Isa’s advice is clear: “Many people see a fire and immediately think, ‘I want to go and help!’ It’s natural to react that way when you discover that the mountains around your hometown are burning, but if you don’t know what to do in a fire situation, you pose a problem. It’s important not to get in the way of the firefighters. I understand that people want to help, but it takes specialists to put out forest fires.”

“If a person walks into an emergency zone to ‘help’, I must neglect the fire, which is why I’m there, to take care of this person who shouldn’t be there”, says Pepe solemnly. “Our priority is always to protect human life, then homes and property, and finally forests and fields. So instead of managing the emergency, we must watch out for this person. Therefore, it is best to stay away and let us do our job.”

After a long day. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 4:21 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 4:21 PM Comments (0)

The story of a rose

Friday, June 27, 2025

Pink therapy. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Several years ago, I received a rose bush as a gift from my dear friend, Jenny. She bought it at a street market in Pruna, a village in the Andalusian hinterland that few people have probably heard of. The rose lived on our terrace for several years in increasingly larger flowerpots. However, no matter where we moved her, whether we gave her new soil or more nutrients, or spoke nicely to her, we only got a few meagre buds during the entire summer season. It was clear that this plant did not thrive in the place where she lived.

One day, we brought her to our organic huerto (allotment garden), dug a large hole in the clayey soil and planted it next to our ‘lavender tree’. The rose settled in almost immediately and started growing out of control. It was as if she had finally found her home. Today, she is a huge bush from which we can cut half a dozen long-stemmed, shockingly pink, heavenly-scented roses every time we visit our garden patch between early May and late November.

The rose in her new home. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The rose from Pruna has become my colour and scent-therapy, because one cannot help but be delighted by her presence. And it is also a joy we happily share with neighbours and acquaintances who have become equally addicted to our rose.

Pink compost! Photo © Karethe Linaae

The province of Málaga, the region of Andalucía and Spain are all places where rich colours surround one. Take the different earth tones - from chalky white and golden yellow to salmon, rust colour and reddish purple. Or all the shades of green in nature, and not to forget the rich blue tones of the sea that go from light turquoise to deep cobalt. Of course, the Spanish food is a colour-chapter in itself, and what about the colourful flamenco culture?

Flamenco dress in window. Photo © snobb.net

Research in psychology and design shows that colour stimuli can affect the emotional areas of our brain. Colours can therefore be mood-enhancing. Strong, bright and highly pigmented colours can have a vitalising effect on our mood and psyche. Being bold and standing out from their surroundings, they can also make us feel more energetic. Warm colours can evoke feelings of happiness, energy, and positivity, while calming and natural hues such as green and blue can reduce stress and promote relaxation. These are therefore often used in therapeutic environments.

Hues. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Surrounding ourselves with colours can make us ‘blossom.’ And just as some of us have lived in places and been in situations where we may not have been able to flourish as much as we wanted or are capable of, we, like our vibrant rose bush, may find a better and more fertile ground in the colourful, bright and cheery Andalucía.

Pink night sky. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 12:48 PM Comments (2)

2

Like

Published at 12:48 PM Comments (2)

Our ‘Home’ in Tangier - Boutique hotel with rock band owners

Friday, June 20, 2025

La Maison de Tanger seen from the garden. Photo © Karethe Linaae

On rare occasions when travelling, one finds a lodging where one feels completely at home. For me, it has only happened a couple of times. Once at an Inn on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, after a secret nuptial ceremony, and once in a picturesque Haveli in Pushkar (famous for its camel races) in Rajasthan. But then, we discovered La Maison de Tanger in Morocco, and there it was again – this feeling of having come ‘home’. My husband and I have returned several times since, and when we finally met the rock musician owners, it became clear why this North African refuge is so unique. So, if you are looking for that special home away from home, join me on a trip across the Strait of Gibraltar to our 'home' in Tangier.

Tea time on the terrace. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

What is a home, anyhow? It’s where someone lives - a house, a flat, a castle or a tipi. But beyond a physical dwelling, a home is a feeling. Subtle elements such as colours, smells, sounds, and the general vibe contribute to this sensation, which is sadly lacking in most public lodgings. Hotels are usually too big, which disqualifies them from being homey. With their uniformed staff, endless hallways, muzak and that universal hotel smell, they are too impersonal. Yesteryear’s Bed and Breakfasts would often be cosy and home-like, but I always felt like I was staying with someone’s nosy aunt. Airbnbs are usually far too generic with their anonymous proprietors and exterior key boxes, which means that perhaps boutique hotels are the closest one can come to a welcoming home away from home. And that is what we found in Tangier.

Pool at night. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

The city of whispers

It is described as a city of whispers. A place where the past meets the present and poetry lives in the very air you breathe. Much has been written about Tangier, especially by the Beat Generation, a group of writers, poets and artists who lived here in the 1950s and 60s. Though they are all gone, new artists have arrived in their place, ensuring that Tangier still exudes that explorer’s vibe. As for us, we are mere travellers coming here for a long weekend. Yet, we are always enchanted by this city, whose stories are carried by the coastal winds.

Vista Tangier. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The ferry from Tarifa in Southern Spain brings us straight to Tanger Ville port, from where one can easily walk up through the gate of the old city wall and end up in the bustling streets of the Grand Souk. But we have not come here to haggle over carpets or Babouche slippers. We pass the lively sales stalls, the cake sellers balancing their heavy trays, the motorbikes zooming dangerously near lost tourists, and the bars filled with a mostly male coffee-drinking clientele. Soon, we exit at the other side of the Souk, crossing a couple of streets, passing the cemetery on the hill, turning right and left, and we are ‘home’!

La Maison

Entrance. Photo © Karethe Linaae

La Maison de Tanger is like a sophisticated traveller’s refuge, something one senses as one’s eyes meet the generous abode in a classic Moroccan style with that undefinable Tanger twist. There are no glaring hotel signs, merely a brass plaque by the door, enveloped by tropical trees and plants - another surprising thing about this North African coastal city. It is lush. In every tiny gap between buildings, even in the incredibly narrow streets of the Kasbah, you will find towering palms, flowering bushes, and trailing ivy.

Reflections. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

As soon as we ring the bell, the door opens with a familiar Bienvenue! The staff is yet another reason why we love La Maison. All are multilingual Moroccans (Oussama speaks Swedish!) except the ever-helpful French-Canadian manager, Sandra. Today, Zakaria is at the front desk. He and I have been communicating to arrange my interview with the owners so that it won’t coincide with the band’s touring schedules and recording plans. And this weekend, it is about to happen!

Berber walls

Garden room. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

But first, we go to ‘our’ room (one of nine), as we, like almost every guest who returns, want ‘our’ room back. It is just that type of place.

Our special room features a deep crimson ceiling and charcoal walls, accented with original framed art, evoking the ambience of a guest room in a globetrotting, artistically minded friend's home. It is neither among their biggest nor best rooms, which usually face the jungle-like garden with the pool. But since our first stay here, it is as if we belong in this room with the picture of the Arab boy on the wall.

From 'our' room. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Speaking of walls, the entire hotel has a Tadelakt plaster wall finish - a beautiful, more than 2000-year-old Berber technique that leaves the walls smooth as silk yet hard as stone, with subtle colour differences. The choice is no surprise, as the original owners, a French architect and his partner, displayed excellent taste when creating their Maison. The feeling is embedded in the Moroccan hues and the carefully selected textures and pieces of furniture. The garden terraces, where I often bring my laptop to work, and the living room encourage relaxation. At night, the city beckons with its beautiful sunsets, but a date on la Maison’s rooftop is sometimes all one needs to sense the heartbeat of Tanger. As one guest perfectly put it, “La Maison de Tanger is the journey within the journey” (le voyage dans le voyage). Staying here is a journey in itself.

Maroccoan style. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

Only a few other guests are dining with us in the living room this evening. There is no menu, as Ilham, the cook, goes to the market, buys what is fresh and available and serves up a tajin feast that makes our mouths water. And thanks to the new owners, the playlist is chill, and there is wine to be had, which is not a given in this country.

Meet the band

Band at home in Tangier. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

The following day, the Canadian owners, Alex Henry Foster Band (formerly Your Favourite Enemies), appear. The band members willingly assist in serving coffee and clearing tables - quite a surprise for what many would describe as rock stars. But then again, they are not your garden variety band. Alex, their visionary leader, has a brief hour for me before it is back to work on two albums coming out later this year. I am curious about how they ended up as hotel owners. However, to understand this, we must start at the beginning.

Alex grew up in a humble family on the east side of Montreal, where they “moved ten times before I was seven”. The one thing the family didn’t lack was music, and in 2006, Alex started the world-renowned band Your Favourite Enemies (YFE).

-We were just a bunch of friends who became professional musicians, touring the world.

Concert photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

Every time they did a show, the band reinvested the proceeds in recording equipment, editing software, and video equipment, eventually becoming completely independent. This is how the church they brought as their home and musical headquarters helped them during Covid, when most musicians “played the ukulele in their bathtubs”. Eventually, the band established their record label, Hopeful Tragedy Records, a merchandising company and even a vinyl pressing plant. But, as Alex points out, the main objective has always been and still is to commune with people.

Band HQ and home in former Montreal church. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

YFE’s last album, Between Illness and Migration, became so successful that they could have kept touring forever based on that record. But the hectic life had taken its toll on the band leader, who needed a change. He brought the band to Morocco, where they travelled around for several months. And when Alex was supposed to go to Barcelona to write their next album, he decided to stay in Tangier.

-I just felt I had to be here. I was a bit lost and confused, and just like anyone who is lost and confused, I was probably the last to know. But here in Tangier, I was able to find some balance and perspective.

Alex at La Maison de Tanger. Photo © Karethe Linaae

That was the beginning of their new adventure. What was originally a couple of months ended up being almost two years, during which time Alex grieved the loss of his father and wrote on the roof terrace of the place where he was staying. The band encouraged him to release what he had written, and it became a very personal and intimate record called Window in the Sky.

-Nothing was planned, which is how all the magic happens with me. I didn’t want to be ‘famous’ again, but the album received a lot of attention.

The original six band members were back together, this time as Alex Henry Foster Band, playing what they call “cinematic, Prague-style experimental rock”.

Buying a hotel during a pandemic

Detail. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When the world shut down due to the global pandemic, the band was quarantined in their large recording facility outside Montreal while Alex composed in his home in Virginia. It was also around this time that he started thinking about buying a place in Tangier.

-There is a real spirit here that you don’t find anywhere else.

Friends recommended they look at La Maison de Tanger, which the band viewed via Zoom from their bases in Montreal and Virginia. Between lockdowns, Alex, Jeff and Isabel from the band managed to travel to Morocco to see the hotel in person.

-We walked in and loved it, exclaims Isabel, who has joined the conversation.

In addition to managing their record label, this vibrant Montrealer sings and plays keyboard, flute, clarinet, trumpet, and saxophone with the band.

Isabel Paradis with her sax. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

-Thankfully, the hotel had an excellent reputation and staff who helped us from the get-go. As artists, we have very little interest in renting rooms, whereas creating an experience is something we like to do, she explains.

Hospitality was completely new to the band, but they knew how to work with the public and make people feel welcome.

-When we arrived to sign the papers, the owners just gave us the key and said, “You’re in charge now”, and left, recalls Alex.

They immediately needed to regroup. Isabel took the front desk, Jeff, who is a French chef, took the kitchen, and Alex walked around with a glass of wine, talking to the guests.

- It started like that! We had to learn fast, as borders were opening, and we were already fully booked.

Since the hotel was busy, they ended up buying a house in the old Medina, where they established their Moroccan home base, combined with a smaller recording facility. But Isabel admits that being a musician is a very nomadic lifestyle.

-When you are in a band, your identity is just that. It is almost like a marriage. But music is our tool to impact the world and our calling. And if it isn’t music, we try to impact the world positively in some other way - like with a hotel …

Favourite reading corner. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

Part of their small contribution to Tangier is that they can hire local staff and support a little ‘ecosystem’ of families. They like to live like and with the locals, and most of their friends are Moroccan. It might surprise some that the band still has not performed in town, but the band leader prefers it this way.

-I like to be Alex around here. I know how quickly things can change when people see you in a different environment. That is why I never want to mix those two universes.

I am just happy to be the guy who feeds the dogs.

My time is up, and the band is off for other engagements. The final recordings for their upcoming album will be done in their facilities in Montreal before they go touring, once again.

On tour. Photo © Alex Henry Foster Band

We have one more night in La Maison before we head back across the Strait to Spain. But we hope to return to our Tangier ‘home’ soon to spend another evening on the roof terrace listening to the Muezzin’s call to prayer while gazing over the rooftops towards the Mediterranean.

Night. Photo © La Maison de Tanger

5

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

5

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

LA Almazara The World’s First Signature Olive Mill

Thursday, May 8, 2025

Welcome to LA Almazara. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When the international press writes about the Andalusian inland town of Ronda, they almost always talk about the historic bridge or Spain's oldest permanent bullring. Therefore, it was a big surprise when the prestigious American TIME Magazine chose a brand-new building in the Tajo-city as number one on their list of the World's Best Places to Visit in 2025.

Welcome to LA Almazara, the world’s first signature olive mill designed by internationally renowned designer Philippe Starck. The cubic building that towers over the landscape between olive groves has been both highly praised and condemned. But anyone interested in architecture, design, engineering, industry, art, sculpture or agriculture, should visit what Starck himself describes as “an unusual, incredible and miraculous place where visitors can enjoy a powerful experience that challenges and transforms”.

LA Almazara, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

TIME's annual travel guide, selected by editors and experts from around the world, distinguishes 100 establishments, including hotels, museums, cruise ships, and restaurants, that offer visitors an experience unlike any other. And this year, the number one spot went to the province of Málaga. TIME recognises the completion of a project that has created an authentic ‘cultural revolution’ on the national stage and has brought journalists from around the world to the small city. I had a chance to join their marketing manager, Jorge Amat, and a group of journalists from Madrid and Morocco on a press tour.

Idea from the wine industry

Merging art and industrial design. Photo © LA Almazara

The new demonstration mill facility on LA Organic Olive Farm is located on a 26-hectare property on the outskirts of Ronda, Andalucía. The founders got the idea to create a designer olive oil mill in 2010 after a visit to the Marqués de Riscal signature vineyard in Álava, designed by architect Frank Gehry. The dream of a signature olive mill was born in 2014 with the idea of transferring the concept from wine to olive oil. Since the owners were already producing organic oil and wine at LA Organic with Philippe Starck as partner and designer, Ronda became the natural location. However, it took almost ten years and an investment of over €22 million before LA Almazara could finally open its doors in October 2024.

Between the olive trees. Photo © LA Almazara

“We never thought that the reception would exceed all our expectations when we had the idea of creating the first signature oil mill in the world,” says LA Organics CEO, the young and dynamic Santiago Muguiro, who believes that the initiative could mark a before and after in the Premium olive oil sector.

Building or sculpture?

LA Almazara – building or sculpture? Photo © Karethe Linaae

One cannot avoid noticing the 28-meter-high, 3,000-square-meter rust-coloured monolithic cube that looks as if it has been dropped down from space. LA Almazara, a word of Arabic origin meaning Oil Press in Spanish, is surrounded by ancient oaks and 6,500 olive trees growing organically, without fertilizers or pesticides. Every detail of this avant-garde project is created to be simultaneously functional and provocative - one of Starck's distinguishing characteristics.

The assembly line for olives leads straight into the building. Photo © Karethe Linaae

"It's more art and sculpture than architecture", he says of the project, which fuses Cubism and Brutalism with industrial design. Yet the building's terracotta hue from natural pigments gives it an overall organic feel.

What might be Starck's most unique work combines architectural innovation with Andalusian agricultural traditions. The design also praises the country's matador traditions, with a giant steel bull horn piercing the building's facade. Therefore, I am particularly impressed when Jorge informs us that all the craftsmen involved in the project were local.

Philippe Strack's design detail exterior. Photo © LA Almazara

Each design element has its unique meaning. In addition to the unmistakable horn, the bull’s symbolic ear is shaped like a colossal olive – a tribute to the fruit and the oil. The bull’s mouth – a spectacular terrace with views of the Sierra de Grazalema – is held up by massive freighter chains, a reference to the Phoenicians who were the first seafarers to settle on the coast of Málaga. One might mistake the fourth element as the eye of Málaga artist Pablo Picasso, says Jorge, but like all artists, Picasso was also influenced by the past. His and now LA Almazara’s eye is a copy of the eye that Phoenician seafarers painted on the bows of their boats, both to protect their ships and crews and to deter enemies.

Picasso’s eye has roots back to the Phoenicians. Photo © LA Almazara

In all its artistic splendour, one mustn’t forget that the building has a practical function. Walking towards the entrance, we see the conveyor belt where the olive fruit is brought into the building during the harvest of LA Organics' approximately 80,000 kilos of home-grown olives.

Mill and Museum

LA Almazara interior. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about LA Almazara is the transformation from being outside to being almost engulfed by the building's magical and semi-dark interior. The entrance takes us through a narrow hall - a visual transformation to the cube’s interior that is as formidable as the outside yet somewhat intimate.

An interior that never ceases to surprise. Photo © La Almazara

“My idea was to show respect for Spain and Andalusia, the most passionate country I have known in my life”, says Starck. He does this, among other things, through a ceiling canvas, painted by his daughter, depicting a woman – the symbol of the country's peasants.

Ceiling art by Ara Starck. Photo © LA Almazara

Starck also pays tribute to two locally born heroes, the legendary bullfighter Pedro Romero (1754-1839), and the scientist, inventor and philosopher Abbás Ibn Firnás (810-887 AD). A forerunner of aviation, the latter designed, constructed and tested the world’s first device to fly for several minutes in the year 875, 600 years before Leonardo da Vinci drew his models of aeroplanes and helicopters. Starck’s replica of his ‘hang glider’ now hangs from the ceiling of LA Almazara.

Starck’s replica of Abbás Ibn Firnás (810-887 AD) flying machine. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The oil mill is otherwise fully operational, although only during harvest season when the finest part of the oil production happens here.

Olive mill interior. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The olives follow an enormous pipe that extends through the building to reach the press and oil tanks on the lower level, which can be seen through floor-based glass panels.

Even the mill in the basement has Starck's signature. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Interactive exhibits show the historical uses of oil, from canning to lighting and soap-making to hydraulic car suspension. The museum tour also demonstrates the unique properties of extra virgin oil for health, nutrition and gastronomy. My personal favourite, however, is the theatrical plaza stage opening to the bull's mouth - an unbeatable terrace with a vista of the surrounding mountains.

The plaza. Photo © Karethe Linaae

This is part of Starck's paradox: "It's an enormous material substance, but once you enter, the weight of abstraction gives way to pure emotion."

View from La Almazara, Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

LA Almazara has positioned Ronda as a reference point for avant-garde design with a project honouring the region's agriculture, cultural history and olive traditions. Don’t miss visiting next time you head to La Serranía de Ronda!

LA Almazara amid nature. © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 5:57 PM Comments (4)

4

Like

Published at 5:57 PM Comments (4)

Who is messing with our time???

Wednesday, April 2, 2025

Spring in Technicolour. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I've never been a conspiracy theorist, but has anyone else noticed that somebody or something is messing with our time?

As a youngster, hearing older people complaining about how fast time passed, I wondered what their problem was since my time felt infinite. But now that I have become one of the ‘oldies’ myself, I couldn’t agree more. I can swear that the Earth is spinning faster and that all universally accepted time segments have been shortened without anyone informing humankind. Forget seconds, minutes, hours and days. A week is nothing anymore because as soon as Monday is over, it’s already Friday. And the year that began a nanosecond ago is already in its second quarter.

Intergalactic movements? Photo © Karethe Linaae

Our age certainly has something to do with our concept of time. For a one-year-old, that year is their lifetime. A child turning five will experience the year as 1/5 of their life, while for someone turning 100, those 365 days will represent 1/100 of their life, so it's no wonder that years feel shorter as we grow older.

Eve. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I do not doubt that the 21st century’s unstoppable technological advances, information flood and endless pressure to perform make our time feel more compressed. There is also more light in our existence, and light - which equals information - increases the feeling of acceleration. At the same time, there is evidence of an acceleration in the Earth’s ‘pulse’ (the so-called Schumann resonance), making time on Earth pass faster. Not to mention the universe’s expansion, the influence of dark matter, the shift of the poles and other forces most cannot even fathom. In other words, this feeling that many of us sense may have a justified reason to be. Furthermore, it may explain why so many people are always in a hurry. Perhaps the body is trying to synchronise with the Earth’s accelerated pulse?

Into space. Photo © Karethe Linaae

What to do? The great Einstein concluded that time is relative, and the only value of time lies in what we do while it passes. So instead of worrying about global acceleration, maybe we should stop and feel April in the air, listen to the birds or talk to each other without finding excuses for why we ‘have’ to run.

Larger than life. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The Spanish have an expression that goes Hay más tiempo que vida, which means that there is more time than there is life. For humans living here and now, time is practically infinite, but as most have realised, our life is not. Therefore, we are better off cherishing our moments and ensuring we follow Einstein’s advice and do worthwhile things while our precious time speeds along.

Just do it! Photo © Karethe Linaae

3

Like

Published at 9:47 AM Comments (2)

3

Like

Published at 9:47 AM Comments (2)

HAMMAM حمّام Andalucía’s Arabic Spa Tradition

Tuesday, March 11, 2025

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

What we think of as modern spa treatments are far from new. Mankind's attraction to warm water and well-being goes back to antiquity. Both the Greeks and the Romans had very advanced public bathing cultures, but it was the Arabs who perfected it here in Andalucía. One can visit the ruins of these baths from the Al-Andalus era in several places in the region. However, for those who want to step into history with body and soul, why not visit one of the region's many Andalusian Hammam baths?

What is a Hammam?

Photo © Aguas de Ronda

Hammam is a public indoor bath traditionally associated with Islamic communities. The cultural heritage that drew heavily from the classical Roman baths quickly became an institution in Muslim countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia, South-Eastern Europe and Al-Andalus - the Islamic Iberia that covered large parts of Spain and Portugal.

In Islamic cultures, baths had both a religious and a civil function. They met the need for ritual washing and ensured general hygiene long before people elsewhere had running water in their homes. The baths also served a social function and offered a gender-separated meeting place for men and women. Archaeological remains testify to the existence of hammams from the Umayyad period (7th-8th centuries), and in many areas, the importance of the baths has persisted to this day. The hammam culture is still widespread in Morocco, where many Moroccans go to hammams weekly. But Andalucía has not forgotten its Islamic bathing tradition.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The architecture evolved from the original Roman design with large thermae or pools to the use of steam, but they still included a similar sequence - a cold room, hot room, steam room, dressing rooms and rest and reception areas. The heat was produced by wood ovens that supplied hot water and steam, while hot air and smoke were led through pipes under the floor, almost like underfloor heating.

Baños Árabes Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Timeless tradition

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

Today, this bathing tradition often takes place in beautiful historic buildings that have become places for relaxation and enjoyment. Although the term hammam is frequently used synonymously with baño turco (Turkish bath), my understanding is that hammam uses more steam.

In modern hammams in Andalucía, where both sexes go simultaneously, swimwear is required, while in traditional hammams divided by gender, a loincloth may be enough.

Photo © Hammam Al Andalus, Córdoba

The sequence starts in a lukewarm pool and goes to increasingly hotter and steamier rooms, while we, the Nordic guests, are possibly the only ones tempted by the icy baths. In traditional hammams, one is washed by a male or female assistant (traditionally always the same gender as the visitor) with soap and a powerful scrub before the treatment ends with a rinse with warm water. In Roman and Greek baths, the bathers mostly sat in stagnant water, but in traditional hammams, people were washed with running water, according to the requirement of Islam. Nevertheless, there were several smaller pools in the baths in Al-Andalus, as evidenced by today’s bath ruins.

Try yourself

Before we descend into the balmy comfort of the hammam, I recommend visiting one of the many historical ruins preserved in Andalucía that will explain these baths' historical, social, archaeological, architectural, artistic and aesthetic aspects.