Why is Flamenco a Spanish Art Form?

Friday, April 28, 2023

Flamenco music has its roots in the Andalusian region of southern Spain and is believed to have originated from the fusion of various cultures, including Spanish, Roma (Gypsy), and Moorish (Islamic) traditions.

The Roma people, who arrived in Spain in the 15th century, played a significant role in the development of flamenco, bringing with them their own musical traditions and influences from their travels throughout Europe and Asia. They integrated their music with the music of the Andalusian peasants and the Moors, creating a unique and expressive form of music and dance.

Over time, flamenco evolved into a highly refined art form, with distinct regional styles and variations. Today, flamenco is considered an essential part of Spanish culture and is recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Flamenco has a long and rich history in Spain, and it has become an important part of the country's cultural identity. While it has gained popularity in other parts of the world, such as Japan and the United States, it remains most closely associated with Spain.

There are a few reasons why flamenco has remained primarily a Spanish art form. For one, it is deeply rooted in the country's cultural heritage and history, and its distinctive rhythms, melodies, and dance moves are intimately connected to the landscape and traditions of Andalusia.

Additionally, the flamenco community in Spain is incredibly tight-knit and protective of its art form. Flamenco artists often train and perform together from a young age, and there is a deep sense of pride and ownership over the tradition. This has made it difficult for flamenco to be fully embraced or replicated outside of Spain.

Finally, it's worth noting that while flamenco is primarily associated with Spain, it has actually been influenced by a variety of cultures and traditions from around the world. Over the centuries, Andalusia has been a melting pot of different ethnic and religious groups, and flamenco is a reflection of this diversity. So in some ways, flamenco is a truly global art form, even if its heart remains firmly in Spain.

1

Like

Published at 7:54 PM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 7:54 PM Comments (1)

The Origins of the Spanish Language

Thursday, April 20, 2023

The "Camino de la Lengua" (the path of the Spanish language) starts from the San Millán de la Cogolla Monasteries in La Rioja and passes through five locations that have had a special and unique relationship with the history of the Spanish language in Spain: the Santo Domingo de Silos Monastery in Burgos and the cities of Valladolid, Salamanca, Ávila and Alcalá de Henares.

The Yuso and Suso Monasteries are in the village of San Millán de la Cogolla and are European Heritage Sites. They are in the Cárdenas Valley, a tributary of the River Najerilla, in the foothills of the Demanda Mountains and under La Rioja's highest peak, San Lorenzo (2,262 metres). Suso, the upper of the two monasteries began in the caves inhabited by the hermits and disciples of San Millán in around the 6th century. The building work that turned these caves into the monastery is reflected in the different architectural styles layered on top of each other from the 6th to the 10th centuries: Visigoth, Mozarabic and Romanesque.

Suso's cultural importance comes from the collection of manuscripts and texts written at the Monastery's library, one of the most important during Spain's Middle Ages: the Codex Emilianense de los Concilios (992), the Quiso Bible (664) and a copy of the Apocalypse by Beato de Liébana (8th century) make this one of the most important, if not the most important, libraries during Spain's Middle Ages. This setting provided the backdrop for what is today the oldest written evidence of the Spanish language.

The Yuso Monastery was built to expand the Suso Monastery in the 11th century and is particularly large. It was built during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries and combines different architectural styles: mainly Renaissance and Baroque. The Monastery's museum houses many wonderful works of art: paintings by Juan de Rizzi (thought to be the best Spanish religious painter) and copper pieces dating back to the 17th century. The 11th century gold and ivory chests hold the relics of San Millán. The screen closing off the church's lower choir was made in 1676 and the retrochoir's sculpture contains eight beautiful Spanish images One of the Monastery's best pieces is also in this area: a pulpit made of walnut, which is thought to date back to the late 16th century.

The Monastery's library and archive are of particular interest and are considered to be one of Spain's best. The Medieval archive's main items are two cartularies (the Galicano and the Bulario cartularies) containing around three hundred original documents.

The library remains as it was furnished towards the end of the 18th century. The true value and interest of the library is not so much the number of documents it houses (over ten thousand), rather the unusual nature of the items. One of these unusual pieces is the "Gospel of Jerónimo Nadal", printed in Antwerp in 1595. Although it is unusual to own a copy of this edition, the actual format of the book is even more unusual, as all the sheets are painted one by one in various colours.

1

Like

Published at 12:52 PM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 12:52 PM Comments (0)

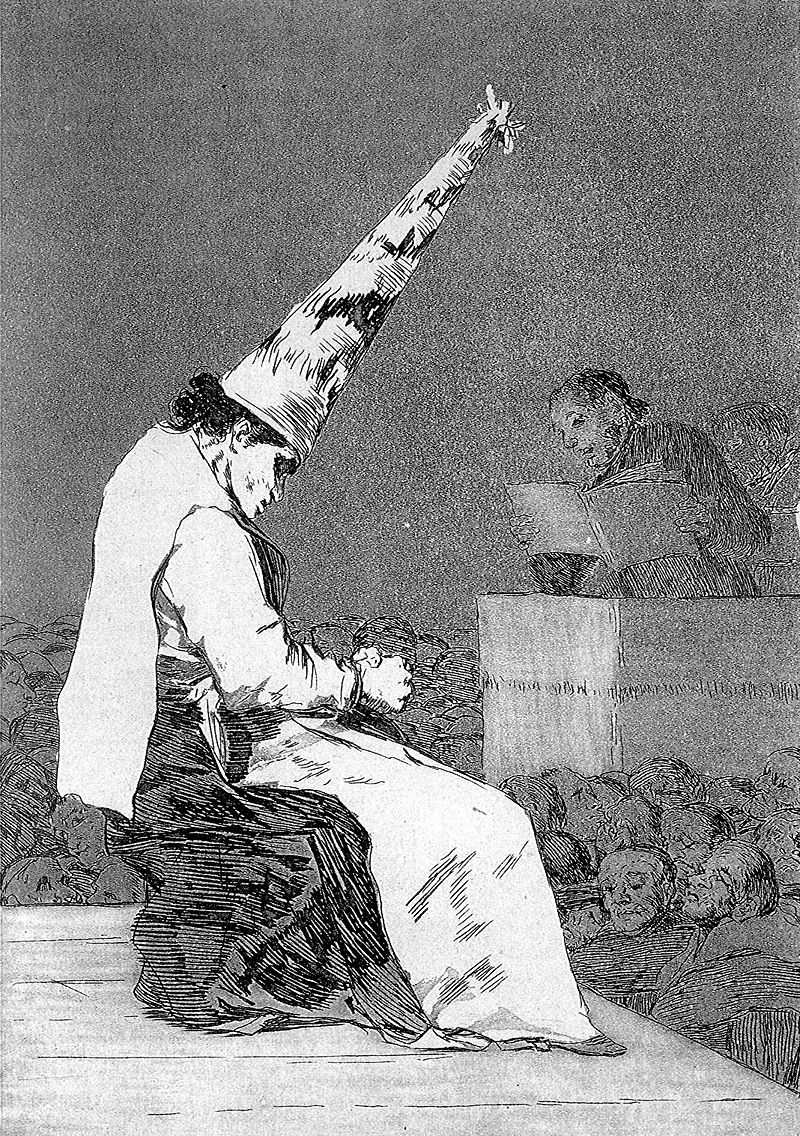

The Capirote - Conical hat worn during Easter processions

Thursday, April 6, 2023

A capirote is a pointed conical hat that is used in Spain. It is part of the uniform of some brotherhoods including the Nazarenos and Fariseos during Easter processions and reenactments in some areas during the Holy Week in Spain.

Historically the flaggelants are the origin of these current traditions, as they flogged themselves to do penance. Pope Clemens VI ordered that flagellants only under control of the church could perform penance; For this he decreed "Inter sollicitudines". This is considered one of the reasons why flaggelants often hide their faces.

The use of the capirote or coroza was proscribed in Spain and Portugal by the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Men and women who were arrested had to wear a paper capirote in public as sign of public humiliation. The capirote was worn during the session of an 'Auto-da-fé'. The colour was different, conforming to the judgement of the office. People who were condemned to be executed wore a red coroza. Other punishments used different colours and drawings to show the punishment to be received.

When the Inquisition was abolished, the symbol of punishment and penitence was kept in the Catholic brotherhood. However, the capirote used today is different: it is covered in fine fabric, as determined by the brotherhood. Later, during the celebration of the Holy Week/Easter in Andalusia, penitentes (people doing public penance for their sins) would walk through streets with the capirote. The capirote is today the symbol of the Catholic penant: only members of a confraternity of penance are allowed to wear them during solemn processions. Children can receive the capirote after their first holy communion, when they enter the brotherhood. When the Inquisition was abolished, the symbol of punishment and penitence was kept in the Catholic brotherhood. However, the capirote used today is different: it is covered in fine fabric, as determined by the brotherhood. Later, during the celebration of the Holy Week/Easter in Andalusia, penitentes (people doing public penance for their sins) would walk through streets with the capirote. The capirote is today the symbol of the Catholic penant: only members of a confraternity of penance are allowed to wear them during solemn processions. Children can receive the capirote after their first holy communion, when they enter the brotherhood.

Historically the structure is called the capirote, but the brotherhoods cover it with fabric together with their face, and the medal of the brotherhood that is worn underneath. The cloth has two holes for the penant to see through. The insignia or crest of the brotherhood is usually embroidered on the capirote in fine gold.The capirote is worn during the whole penance. In Sevilla, it is not allowed to enter the cathedral without the capirote.

In New Orleans during the period between the Rebellion of 1768 and the abolishment of the Spanish cabildo, the more risqué Mardi Gras celebrations of the traditionally French Catholic residents were strictly curtailed by incoming Spanish clergy. The anti-Catholic 'second' Ku Klux Klan that arose at the beginning of the twentieth century may have modeled part of their regalia and insignia on the capirote and sanbenito as a sardonic nod to the enforcement of these restrictions on masquerades a century earlier.

2

Like

Published at 5:16 PM Comments (4)

2

Like

Published at 5:16 PM Comments (4)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|