When Christopher Columbus reached the West Indies in 1492, the natives greeted him with fruit, wooden spears and “certain dried leaves which gave off a distinct fragrance.” The Spanish sailors in Columbus’ crew appreciated the fruit but threw away the dried leaves not knowing what they were for. A few weeks later, while on a reconnaissance on the island of Cuba, two crewmen from the ship reported that they watched as natives wrapped the same type of dried leaves in maize and lit one end and inhaled the smoke from the other. Reportedly, one of the sailors tried a few puffs himself and soon became a confirmed smoker, probably the first European to do so.

When Christopher Columbus reached the West Indies in 1492, the natives greeted him with fruit, wooden spears and “certain dried leaves which gave off a distinct fragrance.” The Spanish sailors in Columbus’ crew appreciated the fruit but threw away the dried leaves not knowing what they were for. A few weeks later, while on a reconnaissance on the island of Cuba, two crewmen from the ship reported that they watched as natives wrapped the same type of dried leaves in maize and lit one end and inhaled the smoke from the other. Reportedly, one of the sailors tried a few puffs himself and soon became a confirmed smoker, probably the first European to do so.

Later explorers would learn that the new world was full of smokers and had been for hundreds of years. North American Indians prized tobacco and traded the valuable leaf regularly. While tobacco was usually smoked in simple pipes called “calumets,” Spanish explorers such as Cortez reported seeing Aztec and other Central American Indians smoking flavoured reed “cigarettes” while the natives of Cuba reportedly rolled their leaves into cigars then as now.

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese settlers in Brazil began cultivating their own tobacco for export to Europe. In 1564, Captain John Hawkins and his crew introduced pipe smoking to England and over the next few decades, the demand for American leaves grew significantly. Sir Walter Raleigh is credited with popularizing pipe smoking at the English royal court not long after. A few decades later, John Rolfe brought South American tobacco seed to the Jamestown Virginia settlement and raised the first crop of “tall tobacco” in what is now the U.S. By the 1730s, the first North American tobacco factories had appeared in Virginia manufacturing snuff.

By the mid-19th century, cigarettes were gaining in popularity in Europe. In 1843, the French Monopoly began the manufacture of cigarettes, a form of tobacco consumption which up until then had a reputation as being a “beggar’s smoke”. This name came from the first people to actually make cigarettes, as we know them today. It dates back to 16th Century Seville when the beggars would collect the scraps that were thrown away by the tobacco factories established in the city. They would tear up and crush the broken leaves that were no good for cigars and roll them up in rice paper. This custom continued for centuries and was extended by the Spanish sailors who exported it, so to speak, to all corners of the world. The Spanish were also the first to start manufacturing these cigarettes in the mid-19th century and it then quickly crossed the border into France and what had been a practice only worthy of the lower class became a symbol for the sophisticated upper class of Europe.

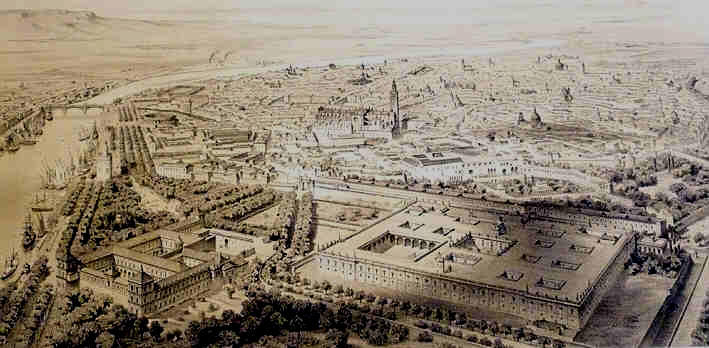

However, in the 18th century, Spain built the Royal Tobacco factory in Seville, which was the gateway for tobacco from the Americas. This 18th-century industrial building was, at the time it was built the second largest building in Spain, second only to the royal residence El Escorial. It remains one of the largest and most architecturally distinguished industrial buildings ever built in Spain, and one of the oldest such buildings to survive. The factory was built just outside the Puerta de Jerez in the land known as “de las calaveras” ("of the skulls") because it had been the site of an Ancient Roman burial ground. Construction began in 1728, and proceeded by fits and starts over the next 30 years. The architects of the building were military engineers from Spain and the Low Countries.

The factory began production in 1758; the first tobacco auctions there (which were the first in Spain) took place in 1763. At that point the factory was employing a thousand men, and two hundred horses, and had 170 "mills" (“molinos”: the devices used to turn the tobacco into snuff, known in Spanish as polvo or rapé); tobacco came both from Virginia and from the Spanish colonies in the Americas. According to the inscription on two of the pillars of the drawbridge on the west side, the building was finished in 1770.

The production of snuff was heavy work: enormous sheaves of tobacco were hauled around manually, and horses turned the grinding mills. For centuries, Seville remained Spain's only manufacturer of snuff. The rising popularity of cigars resulted in part of the factory being adapted for that purpose; cigars were also made in several other Spanish cities: Cádiz, Alicante, La Coruña, and Madrid. Long after the manufacture of cigars elsewhere in Spain (and in Cuba) had become women's work, the workforce in Seville remained entirely male. By the beginning of the 19th century, 700 men were employed in the factory to make cigars, and another thousand to make snuff.

Over time, however, Seville's cigars developed a poor reputation. There were frequent problems with labour discipline, and quality was lower than in the factories where women made cigars; furthermore, men received better wages than women, so these inferior cigars were more expensive than those produced elsewhere. The factory became less profitable. Matters were brought to a head during the Peninsular War. The cigar-making portion of the factory closed in 1811. When it reopened in 1813, it was with a female workforce, then (from 1816) a larger, mixed workforce, and finally (after 1829) an entirely female workforce again, some 6,000 of them at the peak in the 1880s before numbers began to decrease because of mechanization.

Labour unrest was less common among the women than it had been among the men, though by no means was it unknown. There were revolts or strikes in 1838, 1842, and 1885, but none of them was sustained for more than a few days. With mechanization, the labour force reduced to 3,332 in 1906, about 2,000 in 1920, and by the 1940s only about 1,100. Although the interior has been much altered, especially during the adaptation in the  1950s for use by the University of Seville, the Royal Tobacco Factory is a remarkable example of 18th-century industrial architecture.

1950s for use by the University of Seville, the Royal Tobacco Factory is a remarkable example of 18th-century industrial architecture.

The building covers a roughly rectangular area of 185 by 147 metres (610 by 480 feet), with slight protrusions at the corners. The only building in Spain that covers a larger surface area is the monastery palace of El Escorial, which is 207 by 162 metres (680 by 530 feet). There are paintings inside the Tobacco Factory recalling the women cigar makers who worked there. Outstanding among these is the painting by Gonzalo Bilbao, whose most well-known depictions of customs and manners are in the Seville Museum of Fine Arts, including other portrayals of women cigar makers. A ditch was dug around the factory with several sentry boxes, indicating a defensive use. Today it is the headquarters of Seville University.