A thousand tin cans for the Epiphany

Friday, January 2, 2026

By boat, camel, horse, helicopter, on foot, by donkey or even in a convertible ... they will get there any way they can. The three wise men or the Three Kings will visit all towns around Spain on the 5th of January and most towns will organise their festive floats and parades to welcome them but in Algeciras, they will be summoned by an extremely noisy tradition with more than a century of tradition

On January 5th in the morning, before the Three Kings Parade, Algeciras celebrates the 'Arrastre de Latas' (Dragging of Cans), when the children of the city drag a string of tin cans through the streets. This tradition has a couple of explanations the first being an attempt to banish the "Giant of Botafuegos" who every Christmas tries to cover the sea with grey fog, obscuring the star from the Three Kings and thus making it impossible for them to proceed and also impossible to see the port of Algeciras. The noise scares off the Giant and the fog vanishes meaning that the children are able to receive their gifts. However there is another version of this legend: in the olden days when many families were too poor to buy presents, parents told their children that the Three Kings had so much work to do that they were tired and had fallen asleep. Therefore the children decided to make as much noise as they could so that the Kings would hear them and dragging tins through the streets was an effective solution. On January 5th in the morning, before the Three Kings Parade, Algeciras celebrates the 'Arrastre de Latas' (Dragging of Cans), when the children of the city drag a string of tin cans through the streets. This tradition has a couple of explanations the first being an attempt to banish the "Giant of Botafuegos" who every Christmas tries to cover the sea with grey fog, obscuring the star from the Three Kings and thus making it impossible for them to proceed and also impossible to see the port of Algeciras. The noise scares off the Giant and the fog vanishes meaning that the children are able to receive their gifts. However there is another version of this legend: in the olden days when many families were too poor to buy presents, parents told their children that the Three Kings had so much work to do that they were tired and had fallen asleep. Therefore the children decided to make as much noise as they could so that the Kings would hear them and dragging tins through the streets was an effective solution.

Every year over 40,000 children, parents and grandparents attend this traditional ceremony before the arrival of the Kings. On the 5th of January, all participants congregate in the Plaza Andalucia at 11:00 am and at midday they set off for Llano Amarillo near the port, where the Kings are scheduled to arrive at around 13:00 pm.

Melchor, Gaspar and Baltasar for many children are more important than Santa Claus but these three Kings were not always three or even Kings, there was even a time when the three were all white because Baltasar was not black until the sixteenth century. It was at that point that the Church wanted the wise men to represent the three parts of the known world: Melchor: old, bearded, white-haired representing Europe; Gaspar: young blonde on behalf of Asia and Baltasar: black, personifying the African continent. However what is general belief is that these wise men visited Christ on the twelfth day of Christmas, carrying Gold, Frankincense and myrrh.

2

Like

Published at 7:11 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 7:11 PM Comments (0)

The Origin of Churros in Spain

Friday, December 26, 2025

Spain has bestowed upon the culinary world a plethora of favoured dishes. Among them, the churro, a unique doughy delight enjoyed widely across Spain and the world, stands tall. Typically savoured at breakfast or as dessert, often paired with hot chocolate, churros have warmed hearts and homes and merited many queries about their genesis.

The genesis of churros is wrapped in a shroud of mystery and is subject to various theories. Some believe that churros can be traced back to Portugal and Spain's merchants who encountered 'youtiao,' a similar fried dough breakfast treat during their expedition to the East, China to be specific. Intrigued by the concept, the merchants introduced it to their homeland, adding their unique twist in shaping the recipe into the churros we know today. The genesis of churros is wrapped in a shroud of mystery and is subject to various theories. Some believe that churros can be traced back to Portugal and Spain's merchants who encountered 'youtiao,' a similar fried dough breakfast treat during their expedition to the East, China to be specific. Intrigued by the concept, the merchants introduced it to their homeland, adding their unique twist in shaping the recipe into the churros we know today.

An alternate popular theory suggests Spanish shepherds residing in mountainous terrains as the creators of churros. The lack of lush pastures and remoteness from bakeries prompted these shepherds to cook a doughnut-style food over the campfire. The carefully piped dough was easy to prepare and provided a meals-on-the-go option for the nomadic lives of the shepherds. Some conjecture even suggests that 'churro' derives its name from 'Churra,' a breed of sheep whose horns the churros were made to resemble.

Adding another layer to the theories floating around, culinary historian Michael Krondl argues that even if the Chinese fusion theory can be considered, the churro must have been a form of evolution of the 'buñelos,' a deep-fried dough ball popular within the Arab Andalusian cuisine during their rule in Spain. This variety of fried dough has been commonplace in Mediterranean culture since Roman times.

No matter where they came from, churros have solidified their place within Spanish culture for centuries, evolving into slightly sweetened, crunchy treats you could find around the clock. Churros in Spain are typically had during breakfast, dusted with sugar and served with a thick hot chocolate.

Spain's various regions have their spin on the plain churro. In Andalusia, you'll find 'calentitos,' while in Catalonia 'xurros' are thinner, often knotted. Churros made their way from Spain and were twisted to local tastes globally as they became increasingly popular. You could find churros filled with different desserts such as dulce de leche, cajeta or caramel made from goat's milk in Mexico, and fruit fillings in Cuba. Argentina offers churros filled with chocolate, vanilla, or café con leche.

The exact origin narrative of Spanish churros remains slightly blurred across history, subjected to numerous social, and cultural integrations. But their worldwide popularity is proof of their appeal and gastronomical wonder. Whether savoured on Spanish streets or at hometown fairs, their location seldom matters. The joy that the soft-on-the-inside and crunchy-on-the-outside brings is universally shared.

3

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 5:09 PM Comments (0)

12 Grapes on New Year's Eve - Why?

Friday, December 26, 2025

Traditions have always aroused a lot of curiosity in me because there is always a reason for them, nothing just happens by chance. Every year I celebrate the tradition of the New Year's Eve grapes and many years ago I wondered why they actually did this and nobody really seemed to know why. Still, to this very day, I am yet to meet a Spaniard who knows the story..... so I always end up telling it, every year!

The very short version of the story, which is pretty much common knowledge, is that wine farmers from Alicante and Murcia promoted the tradition in 1909. They were eager to sell on their large surplus of grapes from the incredible harvest they had had that year. However, although this story has some truth to it, the real origin dates back even further.

If we define the tradition of the New Year's Eve grapes as when twelve grapes are eaten in the Puerta del Sol at 12 am on December 31, which is basically the general understanding, the first written testimony of this goes as far back as January 1897 when the Madrid Press published that in "Madrid it is customary to eat twelve grapes as the clock strikes twelve, separating the outgoing year from the incoming year…" this means that at least in 1896 it was done, and probably many years before that for it to be considered “customary” by the local press.

The plausible explanation for why someone decided it was a good idea to get cold the last night of the year waiting for a clock to strike 12 strokes and choke on a dozen grapes goes back to 1882. That year the mayor of Madrid, José Abascal y Carredano, decided to impose a tax of 5 pesetas for all those who wanted to go out and celebrate the Three Kings on the night of January 5. The purpose of this was not to stop any tradition or start any new ones but to stop the general public from raising hell and getting drunk through the night – this should not be confused with the festive floats and processions which were in the afternoon and open to everyone.

However, it did deprive the vast majority of the locals of partying that night, except for those that were well off, of course. This obviously led to the people rebelling and trying to find a way to let off steam so New Year’s Eve became the night of preference for partying and an opportunity to make a mockery of the recent bourgeois traditions imported from France and Germany. The local newspapers frequently published how the upper class now celebrated the New Year by drinking champagne and eating grapes during the New Year’s Eve dinner, so as an act of protest the working class would congregate in the Puerta del Sol and eat grapes as the clock struck twelve.

This behaviour quickly spread and popularised in the capital, to the point that in 1897 the merchants of the city advertised the sale of “Lucky Grapes” and within just a few years it was known as far away as Tenerife. Now, this is when the Levante wine farmers come on the scene, taking advantage of their surplus production in 1909, they carried out a national campaign to embed and enhance the custom throughout the country and were thus able to sell all their harvest. This behaviour quickly spread and popularised in the capital, to the point that in 1897 the merchants of the city advertised the sale of “Lucky Grapes” and within just a few years it was known as far away as Tenerife. Now, this is when the Levante wine farmers come on the scene, taking advantage of their surplus production in 1909, they carried out a national campaign to embed and enhance the custom throughout the country and were thus able to sell all their harvest.

Clearly, it worked and today there are few who do not welcome the New Year with 12 grapes in their hand and eat them to the sound of each stroke as it counts down to the New Year. Rare is the Spaniard who will risk poisoning their fate for the coming year by skipping the grapes, many don’t finish them in time and it does take a bit of practice but it is the effort that counts, no effort – no luck, well at least that’s what those who don’t succeed tend to say…

For those who cannot be in the Puerta del Sol, they will follow it on television, normally on La Primera which tops the national audience ratings year after year with around 8 million viewers, some 6 million more than second place. Being such an important occasion some people spend a few extra minutes to remove the seeds or peel the skins off their grapes all in an attempt to improve their chances of swallowing them in time. My best piece of advice is: buy small seedless grapes and you’ll have no problem but they are not easy to come by as the traditional grape variety for New Year's Eve is the Vinalopó from the Valencian Community, the one promoted by the wine farmers back in 1909, so if you can't find seedless try to avoid the large juicy ones or you’ll be in trouble and may well choke your way into the New Year, try and pick the smaller ones and at least remove the seeds…. Good Luck and wishing you all a Happy New Year! the national audience ratings year after year with around 8 million viewers, some 6 million more than second place. Being such an important occasion some people spend a few extra minutes to remove the seeds or peel the skins off their grapes all in an attempt to improve their chances of swallowing them in time. My best piece of advice is: buy small seedless grapes and you’ll have no problem but they are not easy to come by as the traditional grape variety for New Year's Eve is the Vinalopó from the Valencian Community, the one promoted by the wine farmers back in 1909, so if you can't find seedless try to avoid the large juicy ones or you’ll be in trouble and may well choke your way into the New Year, try and pick the smaller ones and at least remove the seeds…. Good Luck and wishing you all a Happy New Year!

2

Like

Published at 3:42 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 3:42 PM Comments (0)

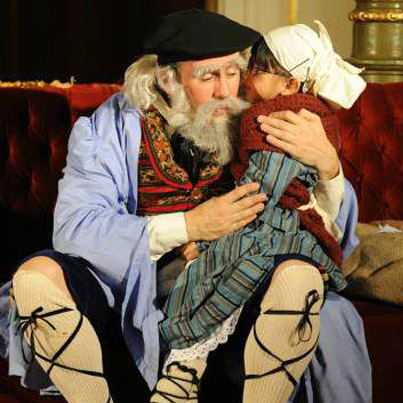

Spain's Christmas Characters

Friday, December 19, 2025

Santa Claus and the Three Wise Men have earned their well-deserved reputation, but they are not Spain's only protagonists during Christmas. Although less known, there are other very peculiar characters who always visit us around these times. From the Olentzero to the Caga Tió, the one who doesn't bring gifts still brings peace and love, something less materialistic but equally important. Discover more about these interesting Christmas characters, maybe one of them will visit your home in the coming weeks....

Basque Country: Olentzero

Olentzero is a coal miner who brings presents on Christmas Eve to those living in the Basque Country and Navarre. Towns, cities, and neighborhoods normally have a procession the day before Christmas with a doll that represents him. Although the origin of this tradition is unknown, some sources indicate that it comes from the winter solstices, when the doll would be set on fire to symbolize the burning of the old to make way for the new; a renewal for the following year. The tradition of fire still continues today but in the modern version the character is someone who comes down from the mountains to announce the birth of Jesus. Olentzero is a coal miner who brings presents on Christmas Eve to those living in the Basque Country and Navarre. Towns, cities, and neighborhoods normally have a procession the day before Christmas with a doll that represents him. Although the origin of this tradition is unknown, some sources indicate that it comes from the winter solstices, when the doll would be set on fire to symbolize the burning of the old to make way for the new; a renewal for the following year. The tradition of fire still continues today but in the modern version the character is someone who comes down from the mountains to announce the birth of Jesus.

Asturias: Guirria and Anguleru

.jpg) This is said to be one of the oldest traditions of the municipality of Ponga. Every New Year's Eve, the boys ride out on horseback accompanied by this half man-half demon character and they roam the streets looking for single women. The character kisses these women as it throws ashes at the boys. But it's not only the Guirria who steals kisses. Single people over 15 years old, both men and women, are paired up by pulling names from jars and they promise to have dinner together one night. Another tradition that still remains today despite the passage of time occurs on the last night of the year and that is when the Guirria and his court go door to door asking for a Christmas bonus. Asturias also has another character who is called l'Anguleru. This character comes from the Sargasso Sea and, like Santa Claus, arrives on Christmas Eve bearing gifts for the little ones. This is said to be one of the oldest traditions of the municipality of Ponga. Every New Year's Eve, the boys ride out on horseback accompanied by this half man-half demon character and they roam the streets looking for single women. The character kisses these women as it throws ashes at the boys. But it's not only the Guirria who steals kisses. Single people over 15 years old, both men and women, are paired up by pulling names from jars and they promise to have dinner together one night. Another tradition that still remains today despite the passage of time occurs on the last night of the year and that is when the Guirria and his court go door to door asking for a Christmas bonus. Asturias also has another character who is called l'Anguleru. This character comes from the Sargasso Sea and, like Santa Claus, arrives on Christmas Eve bearing gifts for the little ones.

Catalonia: Caga Tió and Caganer

Although it may be a bit difficult for the rest of us to understand, in Catalonia children not only receive a visit from Santa Claus and the Three Kings, but also that from a log. It is not just any log, in fact, it is magical and it's called the Caga Tió. It arrives at homes on December 8th and stays until Christmas. During this time, it is always covered by a blanket and is fed daily with food scraps, fruit, and bread. On Christmas Eve, the children sing a traditional song while they hit the Caga Tió with a stick. As a result, this curious character "poops" gifts. The origin of the tradition is said to have come from the logs burned in the earthen fires at home since they provided everything the home needed: heat, light, and even a place to cook. Although the gifts were initially little things like sweets or candies, today the Caga Tió gives all kinds of presents. Although it may be a bit difficult for the rest of us to understand, in Catalonia children not only receive a visit from Santa Claus and the Three Kings, but also that from a log. It is not just any log, in fact, it is magical and it's called the Caga Tió. It arrives at homes on December 8th and stays until Christmas. During this time, it is always covered by a blanket and is fed daily with food scraps, fruit, and bread. On Christmas Eve, the children sing a traditional song while they hit the Caga Tió with a stick. As a result, this curious character "poops" gifts. The origin of the tradition is said to have come from the logs burned in the earthen fires at home since they provided everything the home needed: heat, light, and even a place to cook. Although the gifts were initially little things like sweets or candies, today the Caga Tió gives all kinds of presents.

This character, however, is not the only one with a scatological nature in the Catalan Christmas. Every year the famous Caganer, the figurine of a young herder defecating, appears in the nativity scene. In recent years caganers have been characterized as some of the year's most famous people. This is a tradition that now appears in nativity scenes throughout Spain.

Galicia: O Apalpador

Galicia also has a curious character whose presence during the holidays has recently reappeared although its origin is very old. It is Apalpador, a first cousin of Olentzero, who has the strange habit of coming down from the mountains to pat children's bellies and see if they have eaten well during the year. The figure of this coal miner with a big belly and a red beard lives in the Galician mountains near the regions of O Cebreiro, Os Ancares, and O Courel. He comes down from here on Christmas Night and New Year's Eve. Originally, it was said that he visited homes on these special days to see if children were being well fed and if not, he would leave some chestnuts for them to eat (now he usually brings an extra present too). We can find a very similar character in Ecija, Seville. We are talking about Tientapanzas, the character who visits children at night to see if they have eaten well and then informs the Three Wise Men whether or not they deserve gifts. This tradition resumed in 2004 and since then even a parade through the village streets is held to greet him. Galicia also has a curious character whose presence during the holidays has recently reappeared although its origin is very old. It is Apalpador, a first cousin of Olentzero, who has the strange habit of coming down from the mountains to pat children's bellies and see if they have eaten well during the year. The figure of this coal miner with a big belly and a red beard lives in the Galician mountains near the regions of O Cebreiro, Os Ancares, and O Courel. He comes down from here on Christmas Night and New Year's Eve. Originally, it was said that he visited homes on these special days to see if children were being well fed and if not, he would leave some chestnuts for them to eat (now he usually brings an extra present too). We can find a very similar character in Ecija, Seville. We are talking about Tientapanzas, the character who visits children at night to see if they have eaten well and then informs the Three Wise Men whether or not they deserve gifts. This tradition resumed in 2004 and since then even a parade through the village streets is held to greet him.

3

Like

Published at 4:22 PM Comments (1)

3

Like

Published at 4:22 PM Comments (1)

Thinking in a foreign language makes us more rational

Friday, August 15, 2025

Ever heard this as a child? : “What language do you need me to use so you’ll pay attention?” Ever heard this as a child? : “What language do you need me to use so you’ll pay attention?”

It turns out that there is some truth behind the question. A series of recent scientific studies suggests that we think and make decisions differently if we process the information in a language other than our mother tongue.

Even if we grasp the notion equally well in both languages, our final decision on the matter will tend to be better thought out, less emotional and more results-oriented.

A leading expert on bilingualism at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Albert Costa, believes it is good for deliberative thinking; it makes you think twice about things.

Costa began his research with the tramway dilemma: would you push someone onto the tracks if that death were to save the lives of five other people? The moral conflict involved in sending someone to their death appears to vanish when the question is put to subjects in a language other than their mother tongue.

The proportion of people willing to sacrifice a person for the larger good shot up from 20% to nearly 50%, with the only difference being that they processed the question in a second language.

It appears that processing information in a foreign language makes us less prone to emotional thinking and more focused on efficient results. We become less moralistic and more utilitarian.

The research also finds that thinking in another language increases our tolerance for risk-taking on anything from planning a trip to embracing a new breakthrough in biotechnology.

As the Nobel winner Daniel Kahneman explains, our brain seems to have a System 1, which focuses on fast, instinctive and stereotypic thinking, and a System 2, which deals with issues requiring greater consideration.

In our native language, we may be more prone to using System 1, while the additional effort required for thinking in a foreign language might trigger System 2. This could explain the higher percentage of people who overcome loss aversion and moral dilemmas in a foreign language.

For instance, these insights might be useful during negotiations that require participants to put their personal feelings to one side and focus on the greater good.

3

Like

Published at 4:40 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 4:40 PM Comments (0)

Aircon...before Aircon

Friday, June 13, 2025

Before air conditioning became a household standard, people had to come up with ingenious methods to beat the heat, especially in countries with hot climates like Spain. Spain's rich history and geographical diversity have given rise to various traditional practices to stay cool during the scorching summer months. Here, we explore some of the age-old Spanish tricks that made the summers more bearable before the luxury of air conditioning.

White-Washed Walls

One of the most visually striking and practical traditional methods to keep buildings cool is the whitewashing of exterior walls. This practice was particularly prevalent in the Andalusian region. The white lime paint reflects the sun's rays, significantly reducing heat absorption by the buildings and keeping the interiors cooler. Towns like Ronda and the famous Pueblos Blancos are testament to this effective technique, showcasing picturesque villages that gleam under the sun while providing respite from the heat to their inhabitants.

Thick Walls and Small Windows

Traditional Spanish architecture features homes with thick walls made of adobe or stone and smaller windows than what modern design might dictate. These elements are crucial in insulating the house from the outside heat. The mass of the walls absorbs the heat during the day and releases it slowly during the cooler nights, maintaining a more constant temperature inside the homes. Smaller windows minimized the amount of direct sunlight entering the rooms, further helping to keep interiors cool.

Interior Patios and Courtyards

Many traditional Spanish houses feature an internal patio or courtyard, often with a fountain at its center. This design is not just for aesthetics; it serves a practical purpose in cooling. The courtyards offer shaded outdoor spaces protected from the direct sun, while the water from fountains adds humidity, helping cool the air through evaporation. Plants and trees in these spaces also contribute to a cooler microclimate, offering a pleasant refuge from the summer heat.

Cross Ventilation

Cross ventilation takes advantage of the natural breezes to cool homes. This strategy involves opening windows or doors on opposite sides of a house to allow air to flow through. In traditional Spanish homes, particularly those with inner courtyards, cross ventilation helps circulate air, pushing hot air out and letting cooler air in. This method is most effective during the evening and early morning hours when the outside air is cooler than the inside air.

Night-time Air Flow

Taking advantage of the cooler night air is another strategy employed in traditional Spanish homes. Residents would close their homes during the hot daytime hours to keep the heat out and open them up at night to allow the cool air to circulate through the interiors. Often, families would sleep on rooftops terraces or balconies to escape the day's accumulated heat within the home's walls.

Natural Fabric and Clothing

The traditional Spanish attire, such as the light and airy "flamenco" dresses or the loose, comfortable "camisa de manta," reflects an intrinsic understanding of how to stay cool. These clothes are usually made from natural fibers like cotton or linen, which are breathable and promote the evaporation of sweat, thus cooling the body more efficiently than synthetic fabrics.

Strategic Planting

The strategic planting of trees and vines around homes was another method used to create shade and protect buildings from direct sunlight exposure. Deciduous trees, which lose their leaves in the winter, were particularly valued as they provide shade during the summer while allowing sunlight to penetrate and warm the house during the colder months.

In the absence of modern cooling technologies, these traditional Spanish methods provided effective solutions to the problems posed by the summer heat. Today, with a growing interest in sustainable living practices, these time-tested strategies are gaining renewed attention. They remind us of the ingenuity of past generations and offer inspiration for ecologically responsible design in our quest to stay cool in the heat

3

Like

Published at 11:49 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 11:49 PM Comments (0)

Which Spanish town gets the most rain?

Thursday, May 15, 2025

Would you live in a town that rains every other day? If you are one of those people who love the rain, this town may be perfect for you. This Spanish town in the province of Cádiz is located in the northeast of the province, in the reserve area of the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park.

The name of the town is Grazalema and its rainfall rate is the highest in Spain, registering more than 1,962 mm of average annual rainfall in the municipality. To put that into perspective London has an annual rainfall of around 592mm! And the average for the whole of the UK is 885mm per year. So more than double the UK average. In addition, it is unsurprisingly the home to the source of the Guadalete River.

It is the first mountainous area to encounter the humid Atlantic winds which enter from the southwestern coast, causing the town of Cádiz to have high rainfall. As the water passes through the low and warm lands, this air cools as it increases in altitude, causing the clouds that will later drop the rain.

Grazalema has a considerable variation of monthly rainfall according to the season. The rainy period of the year lasts for 8.5 months, from September 10 to May 28, with a sliding 31-day rainfall of at least 0.5 inches.

Within the municipality, we encounter a Cadiz village with its urban centre that was declared a Historic Site, where you can see various buildings built according to the typical popular architecture.

It also boasts several churches that must not be missed. The first of them, and the most important, is the 18th century Baroque Church of Nuestra Señora de la Aurora, accompanied by the Church of the Incarnation, from the 17th century but renovated in the 19th. We can also find the Church of San Juan, from the 18th century, followed by the Church of San José, from the 17th century. Without forgetting its only hermitage from the 20th century, under the invocation of Our Lady of the Angels.

Benamahoma is the name of the district which the arabas called 'Ben-Muhammad', meaning "sons of Muhammad." In this municipality, the Islamic influence can be seen in the peculiar layout of its streets. You can also go through the Museum of Textile Crafts where you can see artisan objects such as numerous collections of blankets. The town is famous for its traditional handmade blankets.

Without forgetting the fabulous traditional Cadiz cuisine, in Grazalema, you can taste numerous typical dishes. A wonderful example would be the Grazalema soup, a stew broth made with egg, chorizo, bread and mint. Some of its other specialities are the 'tagarninas' or the very typical roast lamb.

1

Like

Published at 7:17 PM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 7:17 PM Comments (0)

Casa das Pedriñas: A Stone-Studded Labour of Love in Rural Spain

Friday, May 2, 2025

Nestled in the picturesque countryside of Veiga, Spain, stands a peculiar and enchanting structure that has captivated the imaginations of locals and visitors alike for decades. The Casa das Pedriñas, or "House of Little Stones," is a testament to one man's unwavering dedication, creativity, and passion. This remarkable dwelling, adorned with thousands of small, polished stones, tells a story of perseverance, artistry, and the extraordinary lengths one person can go to realise their dreams.

The Visionary Behind the Stones

The tale of Casa das Pedriñas begins with Daniel Mancebo, a local miner affectionately known in his hometown as "El Bailarín" (The Dancer). In 1970, Mancebo embarked on an ambitious project that would consume nearly three decades of his life. His vision? To create a home unlike any other, one that would stand as a lasting tribute to his creativity and connection to the land he loved.

Mancebo's journey was not one of instant gratification or overnight success. Instead, it was a slow, methodical process that required immense patience, skill, and dedication. From 1970 until his passing in 1998, Daniel poured his heart and soul into this unique endeavour, transforming a simple house into a work of art that continues to captivate and inspire to this day.

A Labour of Love and Frugality

What makes the Casa das Pedriñas truly remarkable is not just its appearance, but the story of sacrifice and determination behind its creation. Daniel Mancebo was not a wealthy man, nor did he have access to vast resources. As a miner, he lived a modest life, but he harboured grand ambitions for his stone-covered dream home.

To fund his project, Mancebo adopted a frugal lifestyle, saving every peseta he could spare from his earnings. This financial discipline allowed him to slowly but surely accumulate the resources needed to bring his vision to life. It's a poignant reminder that great achievements often require personal sacrifice and unwavering commitment.

Nature's Palette: Sourcing the Stones

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Casa das Pedriñas is the origin of its decorative elements. Daniel didn't simply purchase stones from a quarry or a landscaping supply store. Instead, he embarked on regular expeditions into the nearby mountains, searching for the perfect specimens to adorn his home.

These excursions into nature served a dual purpose. Not only did they provide Mancebo with the raw materials for his project, but they also deepened his connection to the landscape around Veiga. Each stone collected represented a piece of the local geography, effectively bringing the essence of the mountains to his doorstep.

The Art of Transformation

Collecting the stones was only the first step in Mancebo's creative process. Once he had gathered enough raw materials, he set about transforming them into the polished gems that would eventually cover his home. Armed with nothing more than a mallet and his own two hands, Daniel meticulously worked each stone, coaxing out its hidden beauty.

This polishing process was time-consuming and labour-intensive, requiring both physical strength and a keen eye for detail. Mancebo would spend countless hours hunched over his workbench, carefully shaping and smoothing each stone until it met his exacting standards. The result of this painstaking work was a collection of stones that shimmer and gleam, catching the light in a way that brings the house to life.

A Symphony in Stone

As visitors approach the Casa das Pedriñas, they are immediately struck by its unique appearance. The entire exterior of the house is covered in a mosaic of small, polished stones, creating a textured, multi-coloured surface that seems to dance in the sunlight. The overall effect is both rustic and refined, a perfect blend of natural beauty and human artistry.

The stones vary in size, shape, and colour, reflecting the diverse geology of the surrounding area. Shades of grey, brown, and white dominate, punctuated by occasional flashes of quartz or other eye-catching minerals. This variety creates a dynamic visual experience, with the eye constantly discovering new patterns and combinations as it roams across the facade.

More Than Just a House

While the Casa das Pedrias is undoubtedly a residential structure, it transcends the typical definition of a home. In many ways, it serves as a three-dimensional canvas, showcasing Daniel Mancebo's artistic vision and his deep connection to the land. Each carefully placed stone tells a story - of long days spent in the mountains, of evenings dedicated to polishing and arranging, and of a dream slowly taking shape over the course of decades.

The house stands as a prime example of outsider art and vernacular architecture. These terms refer to creative works produced by individuals without formal training, often resulting in unique and deeply personal creations. The Casa das Pedrias embodies this spirit, representing one man's singular vision brought to life through sheer determination and creativity.

A Dream Unfinished

Tragically, Daniel Mancebo passed away in 1998 before he could fully realise his vision for the Casa das Pedriñas. Despite dedicating nearly 30 years to the project, there were still areas of the house that remained unadorned at the time of his death. This unfinished state adds a bittersweet note to the property's story, serving as a poignant reminder of the fragility of human life and the ambitious scale of Mancebo's dream.

The Challenge of Preservation

Today, the Casa das Pedriñas stands as a unique cultural landmark in Veiga, attracting curious visitors from near and far. However, the future of this extraordinary structure remains uncertain. The house is currently abandoned, facing the dual challenges of time and neglect.

The primary obstacle to preserving the Casa das Pedriñas is the high cost of maintenance. The intricate stone covering requires specialised care to prevent deterioration, and the house's unique construction presents challenges not typically encountered in standard building preservation. Mancebo's heirs, while undoubtedly proud of their ancestor's creation, find themselves unable to shoulder the financial burden of properly maintaining the property.

This situation raises important questions about the preservation of outsider art and unconventional architecture. How can society balance the need to protect these unique cultural assets with the practical realities of maintenance costs? Should local or national governments step in to safeguard such properties, or are there other innovative solutions that could ensure the Casa das Pedriñas continues to inspire future generations?

A Source of Local Pride

Despite its current state of abandonment, the Casa das Pedriñas remains a source of pride for the people of Veiga. It stands as a testament to the creativity and determination of one of their own, a tangible reminder that extraordinary things can emerge from even the most unassuming beginnings.

Local legends and stories have sprung up around the house and its creator. Some say that on quiet nights, you can still hear the tap-tap-tap of Daniel's mallet as he works on his beloved stones. Others claim that the house possesses mystical properties, with the stones whispering secrets to those who listen closely. While these tales may be more fiction than fact, they speak to the deep impression the Casa das Pedrias has made on the collective imagination of the community.

The Legacy of Daniel Mancebo

In creating the Casa das Pedrias, Daniel Mancebo left behind more than just a uniquely decorated house. He bequeathed to his community, and to the world, a powerful reminder of what can be achieved through passion, perseverance, and a willingness to pursue one's dreams, no matter how unconventional they may seem.

Mancebo's legacy serves as an inspiration to artists, dreamers, and non-conformists everywhere. It encourages us to look at the world around us with fresh eyes, to see the potential for beauty and creativity in the most ordinary of objects. The Casa das Pedriñas stands as a monument to the human spirit's capacity for imagination and the transformative power of dedicated, patient effort.

Looking to the Future

As we consider the future of the Casa das Pedriñas, it's clear that action is needed to preserve this unique piece of cultural heritage. Perhaps a solution lies in community involvement, with local residents coming together to maintain and promote the site. Or maybe a benefactor will step forward, recognising the value of this extraordinary creation and providing the resources needed for its upkeep.

Whatever the future holds, one thing is certain: the Casa das Pedriñas will continue to captivate and inspire all who encounter it. It stands as a testament to the power of dreams, the beauty of nature, and the incredible things that can be achieved when one person decides to turn their vision into reality, one small stone at a time.

In the end, the story of the Casa das Pedriñas is more than just an tale of unusual architecture or outsider art. It's a reminder of the extraordinary potential that lies within each of us, waiting to be unleashed. Daniel Mancebo's stone-covered house serves as a call to action, encouraging us all to pursue our passions, no matter how outlandish they may seem, and to leave our own unique mark on the world.

0

Like

Published at 11:42 PM Comments (1)

0

Like

Published at 11:42 PM Comments (1)

Napoleon's Spain

Friday, April 25, 2025

In the year 1810, José I, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, the victorious French general who ended up proclaiming himself emperor until his defeat by the British and Prussians at Waterloo, reigned in Spain. In the year 1810, José I, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, the victorious French general who ended up proclaiming himself emperor until his defeat by the British and Prussians at Waterloo, reigned in Spain.

Spain had suffered the French invasion, from which it would manage to free itself in 1814 at the end of the War of Independence and which, according to many analysts, was the beginning of the end for Napoleon.

During this French occupation, the Spanish government sponsored by Paris wanted to administratively reorganise the entire country, and among other changes, wanted to impose a division by provinces very different from the current one.

The design was carried out by José María de Lanz and Zaldívar, who was inspired by the administrative division of France. The idea was to take advantage of natural features and try to make each province approximately the same size.

Lanz did away with historical names and wanted each province to be named after the dominant river or rivers. Thus, there were Ebro and Jalón, Guadalquivir Bajo, Duero and Pisuerga, Segura or Miño Alto.

In addition, new, not necessarily traditional, capitals were established: towns such as Astorga, La Carolina, Ciudad Rodrigo or Jerez became provincial capitals.

Napoleon's Map of Spain

The problem is that this method ignored historical realities and decisions were made such as dividing Zaragoza into two provinces. Finally, the end of the French occupation put an end to this scheme and in 1833 one very similar to the current one would be adopted.

VIDEO IN ENGLISH

0

Like

Published at 10:20 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 10:20 PM Comments (0)

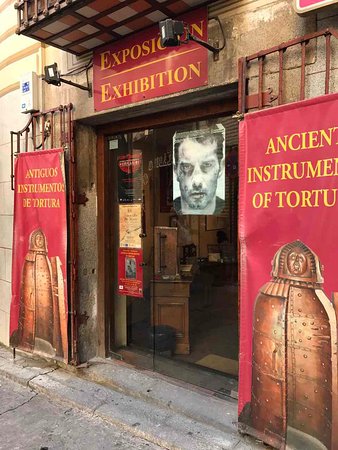

Museum of Torture in Toledo

Friday, April 18, 2025

Toledo, Spain is known as the City of Three Cultures, as Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities have coexisted within its stone walls. The fortified city in Castilla-La Mancha was also the site of fierce persecution during the Spanish Inquisition. On an unassuming corner on the labyrinthine streets of the old city, the Museo de la Tortura displays artefacts from this dark period in the nation’s history and that of other European powers. Toledo, Spain is known as the City of Three Cultures, as Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities have coexisted within its stone walls. The fortified city in Castilla-La Mancha was also the site of fierce persecution during the Spanish Inquisition. On an unassuming corner on the labyrinthine streets of the old city, the Museo de la Tortura displays artefacts from this dark period in the nation’s history and that of other European powers.

The exhibit is spread across five rooms, with insight on the Spanish Inquisition’s origins as well as its methods for torture and execution. Plaques throughout the museum offer descriptions of the tools in both English and Spanish and provide some historical background for the brutal practices of the Inquisition.

While the museum is home to infamous medieval devices like the rack and the iron maiden, it boasts a collection of lesser known instruments of torture. Pieces like the choke pear and chair of Judas demonstrate the sadistic inventiveness at work within the Inquisition, with many contraptions designed to punish specific offences or prolong suffering before death.

Iron Maiden

Interrogation Chair

Tools like the thumb vice were often used to force a confession or repentance, inflicting pain without risking death on the victim. The interrogation seat was lined with spikes that could be heated before a prisoner was locked into place. Some pieces like the Garrote Vil were used long after the Inquisition had ended. The neck-crushing collar was used in Spain as recently as the 1970s.

Judas seat

Shame mask

The side room features contraptions designed for public ridicule, including a heavy wooden barrel held on the shoulders of those accused of drunkenness. The iron shame masks were intended to humiliate the wearer, but also provided a burdensome strain on the prisoner’s body. The museum also displays executor’s hooded garb and axe as well as the tattered Sambenito, a garment worn by prisoners during their public auto-da-fé.

The museum presents its artefacts without sensationalising torture and provides a stark look at the social conditions of Inquisition-era Spain.

1

Like

Published at 7:30 PM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 7:30 PM Comments (1)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|