Columbus was 41 when he was granted the funding to find a route to the orient, though he had spent about ten years touting his theory to every monarch and financial backer in Europe. He was experienced in sailing and navigation and was a member of a small group of sailors who had explored the oceans. He was born in 1451 in Genoa, and initially spoke a dialect of Ligurian as his first language, though he never used it in any of his later documents or letters. His father was Domenico Colombo, a wool weaver, who worked both in Genoa and Savona and his mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartolomeo, Giovanni and Giacomo, as well as a sister named Bianchinetta.

In 1470, the Columbus family moved to Savona, on the coast to the west of Genoa, where his father took over a tavern. The same year, Christopher, aged 17, sailed on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Three years later, he began his training as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa, and in May 1476 young Columbus took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably docked in Bristol, England, and Galway, Ireland. He boasted in his diaries much later that he visited Iceland in 1477, but what is known for sure is that he arrived in Lisbon that same year to join his brother Bartolomeo who worked in a cartography office.

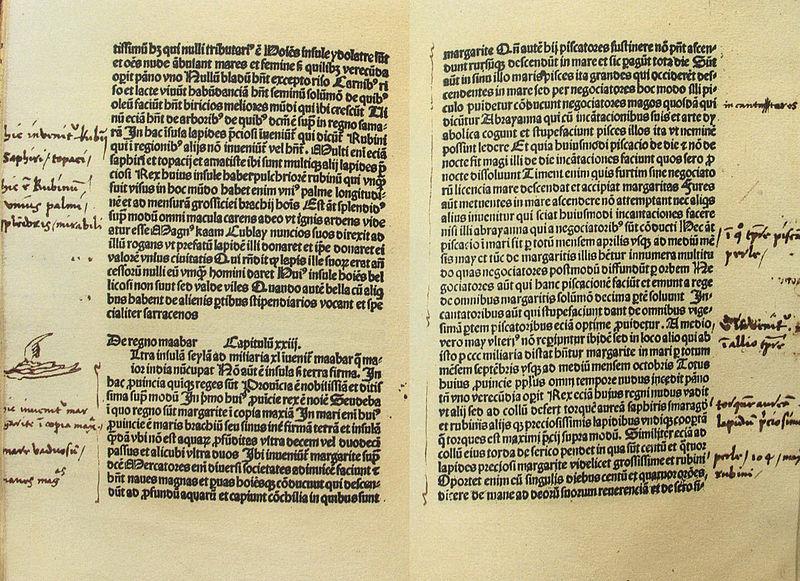

It was in Lisbon that he set up home and married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, daughter of the governor of Porto Santo. Two years later, his first son, Diego Columbus, was born. Christopher was not an academic, yet he learned to read and write in Latin, Portuguese, and Castilian. His reading covered books about astronomy, geography and history and included an impressive list of authors: most of the scientific writings and maps of Claudius Ptolemy, Pliny’s Natural History, Cardinal Pierre d'Ailly’s Imago Mundi, Pope Pius II’s Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum, The travels of Marco Polo, and The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. We know this because his books were preserved and handed down and we can read the copious notes that Columbus wrote in the margins.

Columbus' notes in the book by Marco Polo.

This was a difficult time for traders like Columbus. The Mongol Turks had allowed the free passage of trade goods overland via the Silk Road for centuries, but when the Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, the land route to Asia was closed to Christian traders, and Portuguese navigators tried to find a sea route to Asia.

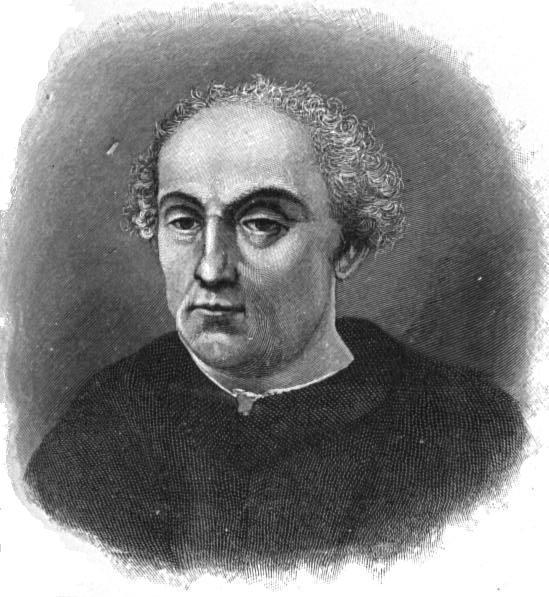

Toscanelli

Toscanelli

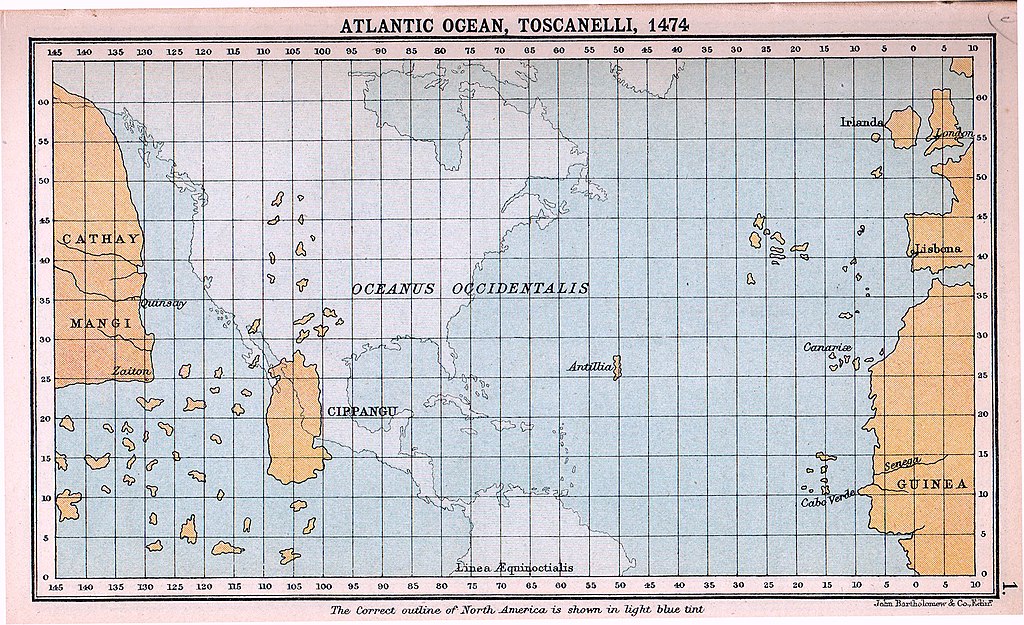

As early as 1470 the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal that sailing west across the Atlantic would be a quicker way to reach the Spice Islands, Cathay (Cina), and Cipangu (Japan) than the route around Africa, but King Afonso rejected his idea.

Columbus and his brother learned of this and made some enquiries which led to Toscanelli sending the Columbus brothers a map in 1481 showing that a westward route to Asia was possible. In the meantime, however, the king encouraged mariners to find another route to Asia by going south, rounding the Cape of Good Hope and passing into the Indian Ocean. In 1488, this is exactly what another navigator, Bartolomeu Dias, did. This took the wind out of the Columbus boys’ sails.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Columbus was employed as a trader, and he was obliged to spend months away at sea. Much of Portugal’s trade was with Africa, and he traded along the Guinea Coast from the trading station of Elmina. Sometime before 1484 he called at Porto Santo in the Madeira Islands where he learned that his wife had died, and that he must return home to take care of his son. With his wife’s estate settled, Columbus and his son left for Córdoba, a centre for many of the Genoese traders and the city where Isabel and Ferdinand has set up their campaign headquarters for the war against the Caliphate of Granada. It was here that he met a 20-year old orphan named Beatriz Enríquez de Arana and took her as his mistress in 1487. The next year, Beatriz gave birth to a son by Columbus, whom they called Fernando, after the King of Aragon.

When King Afonso of Portugal turned down Columbus’ offer to find a new route to Asia across the Atlantic Ocean he had consulted some of the best cartographers and sailors of the time, who in turn had studied maps made by the best thinkers and most learned men of antiquity.

Around 250 BC Eratosthenes had calculated the diameter of the earth with his famous experiment measuring the shadow of a pole of a given length in two different places. He obtained a figure of 252,000 stadia, or 24,662 miles. (actual 24,902 miles.) Five hundred years later, Ptolemy, the author of the Almagest star chart, and giant amongst the philosopher/scientists of antiquity, had drawn a map of the known world. He estimated that the entire Eurasian continent from Portugal to the Chinese coast spanned 180 degrees of longitude. This map had been part of a three volume encyclopaedia on geography which had been translated from Greek into Arabic sometime in the ninth century. The books disappeared in time, but the map was copied by Byzantine monks and published in 1295. The map had been widely reproduced in 1486 and was available to European mariners, whose voyages were filling in the blank spaces around the edges. The most important aspect about the chart was that, as with star charts, he had drawn in meridians which were the first attempt at using latitude and longitude. (Ptolemy was the chief librarian at the library of Alexandria and had access to written information going back centuries.)

Ptolomy's Mapa del Mundo: photo: Francesco di Antonio del Chierico.

If Eratosthene’s circumference for the earth is divided by 360, this will give the length of one degree of longitude at the equator. According to Ptolemy, the whole Eurasian continent spanned 180 degrees, that left another 180 degrees of empty ocean unaccounted for. This means that the distance from Portugal to China going west was 12,331 miles (half of the circumference). This would have been the combined equatorial spans of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans added together. These were the figures supplied by King Afonso’s advisors. No ship of that time was capable of a voyage of that distance without making landfall to replenish essential supplies.

However, Columbus started his calculations with a mistake of the first magnitude. Over the centuries, the circumference of the earth and Ptolemy’s map had been translated from Greek stadia into Arabic miles. Columbus assumed that they were using Roman miles, which are 20% shorter that the Arabic miles. This meant that Columbus’ world was 20% smaller than it really is. His second error was using Marinus of Tyre’s estimate that the longitudinal span of Eurasia was 225 degrees, which would have the effect of reducing the Pacific/Atlanic Ocean by 2,520 miles, and he followed this error up by taking Marco Polo’s estimate that Japan lay 1,500 miles from the coast of China reducing the distance from Portugal to Japan to 9,500 miles. If he sailed from the Canaries, he would reduce that distance by a further 500 miles. Columbus was also influenced by Toscanelli’s claim that there were inhabited islands even farther to the east than Japan, including the mythical Antillia.

Toscanelli's map of the Atlantic Ocean.

The final figure of 9,000 miles is daunting enough, but Columbus had presented his estimate of the distance from the Canaries to Japan as 5,300 miles when he was asking for funding. This is why nobody took him seriously. We know now that the real distance from Africa to Japan is more like 14,000 miles, and it is clear that Columbus and his crews would have disappeared without trace.

The only thing that saved them was something that nobody in the world suspected; just over 3,500 miles west of the Canaries was a huge hourglass shaped continent that stretched almost from pole to pole.

Leif Ericson stepping ashore in America painted by Hans Dahl.

Actually, there were some people who knew that there was a landmass not too far out in the Atlantic. Five-hundred years earlier, the Vikings had extensively sailed in the North Atlantic. The only two known mentions of the new lands are found in the work of Adam of Bremen c. 1075 and in the Book of Icelanders compiled c. 1122 by Ari the Wise. Leif Ericson was a Norse explorer from Iceland, and according to the sagas of Icelanders, he established a Norse settlement at a place called Vinland, which is usually interpreted as being coastal North America. There is still speculation that the settlement made by Leif and his crew corresponds to the remains of a Norse settlement found in Newfoundland, Canada, called L'Anse aux Meadows and which was occupied around the year 1000. The Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders, both thought to have been written around 1200, contain different accounts of the voyages to Vinland.

One story that is neither proven nor denied is that whilst Columbus was returning for his visit to Iceland in 1477 his ship stopped at Galway, and while they were there, he saw a man and a woman who had been found in an open boat in the Atlantic and picked up. Columbus wrote in his notes that they were of a “most unusual appearance.” Columbus must have added this to already stretched-to-the-limit theory about a westerly passage to the orient.

Columbus had travelled to Iceland, where the sagas and history of Lief Ericson were known. Had he learned of his travels and discoveries, he might have tried a more northerly route where there were plenty of stopping off places and sheltered harbours along the way. It might have helped him with his next big problem; finding a crew and captains who were willing to go with him on a suicidal voyage.