A Zen Garden for Christmas

Friday, December 24, 2021

In my pueblo there is always building work going on somewhere. People are always changing and improving their houses, so I was not surprised to see a pile of sand at the bottom of my neighbour’s garden with a shovel stuck in it. A dead giveaway that building work was going on. What did surprise me was the person standing next to the shovel. Many things go together well: cheese and wine, bacon and eggs, fish and chips. Others clash: red and green, oil and water, Loveless and a shovel.

The pueblo had many, shall we say, exotic characters. Very few were Spanish; they had all been normalised very early in their lives by the very conservative natives. The Brits, however, had no obvious constraints to their behaviour. In this respect, Loveless and Geordie were a couple who stood out head and shoulders above the rest. Nobody knew what their relationship was, but like Batman and Robin, even though they were accepted by most, you knew something was not just quite right.

I mentioned that Loveless was standing in close proximity to the shovel, but his body language was screaming that it was nothing to do with him. When he saw me he stepped away from the heap of sand as though it was a pile of warm elephant droppings. Just then, Geordie’s voice screeched from the other side of the garden wall.

“Hurry up and fetch some more cement.” Lovelace’s face dropped. I put on a big smile.

“Hi Loveless, how are things going?” I enquired.

The expression on Lovelace’s face took on a new depth of despair. Imagine one of Napoleon's captains retreating from the gates of Moscow in midwinter. The frozen bodies of his fallen troops piled at the side of the road with Russian snipers and artillery adding to their terrible misery. If you had cheerfully asked the captain, how things were going, the expression that you would have seen would not have been too far from the one Loveless was wearing.

“OK,” he said, with a voice like dropped lead.

Just then, Geordie came through the garden gate with a face like thunder.

“I said mix some more,” he snarled.

“Hi Geordie,” I said.

“What do you want?” he hissed.

“Just passing,” I explained. “What are you up to?”

Geordie drew himself up to his full height so that he could look down his nose at me and haughtily explained.

“I have been commissioned to create a Zen Garden by Pauline.”

I have to confess I was taken aback by this revelation. In Andalusia there is a distinct rarity of Zen Gardens. Meditation and spiritual development are not high on the agenda of the average Andaluz farmer. Knowing Pauline well, I began to have a shadow of doubt about validity of this Zen Garden. It’s usually not a good idea to probe too much into Geordie’s world. It can quickly become very confusing. However I could not resist this particular probe.

“What exactly is a Zen Garden,” I asked.

“It is a secluded space where the inter-dimensional forces of the universe are channelled and controlled. The benign power that flows through everything is focused by the structure of a Zen Garden, bringing good luck and health to the people who inhabit the house. You must arrange certain stones with their relative power-vortices so that the flow of positive energy is pure. You have to say the correct prayers and incantations with each phase of the construction. I have studied the subject exhaustively and have been trained by masters of the art.” he explained.

“Wow! Very impressive,” I answered. “Where did you train to be a Zen Master? I always thought that you were from South Shields.”

“He downloaded it from the internet,” blurted Loveless. “That’s where he gets all his stuff from. He pays 10€ a month for them to send him this crap.”

“Mix some more cement!” Geordie barked, giving Loveless a scathing glare.

“May I take a look?” I probed a little deeper.

“Of course,” Geordie was warming to his new role as teacher of oriental wisdom and bringer of enlightenment. “This first wall is a step down to the rest of the garden. It will be on two levels symbolizing the Yin and Yang of the universe, where each positive force is balanced by a negative force, thus bringing equilibrium to all things.”

We stood at the side of a narrow trench which he had excavated with a gardeners trowel. Geordie had been patting in cement with his hands as a foundation.

“Why not use wooden shutters and just pour concrete in? That’s what everybody else does,” I ventured. Geordie looked at me as though I had just farted.

“Because you would violate the energy field generated by my hands and prayers,” he coldly informed me.

“I see,” I lied.

I decided that I had probed enough for one day and suggested that I would call in from time to time and see how the work progressed. I made my excuses, left the garden of eternal bliss, and stepped into the real world. As I passed I called hasta luago to Loveless, but he did not look up from his mixing. On the way to the shops I was wondering if Zen Gardens had gargoyles, because Loveless’ face would have been a perfect model for one.

Three days later I walked past the bottom of Pauline’s garden and looked over the wall. Pauline and Geordie were bending over the wall dividing Yin from Yang and talking seriously. I foolishly called out.

“How’s the Zen Garden coming along?”

Both heads snapped up and looked at me with very strange, strained expressions. Realizing that I may have put my foot in it I smiled and made an excuse.

“Must go and catch the shops before they close. Byee.”

I returned by the same route a half hour later and cheekily peeped over the wall to see what had happened. As I did so, I saw Pauline alone. She had seen my head pop up and she waved me into the garden.

“What’s all this about a Zen garden?” she demanded.

“Well, Geordie said you had commissioned him to build a Zen garden,” I explained.

“Zen bloody garden my arse! I told him to build a wall so I could have two levels of reasonably flat garden. Just look at this,” she snarled.

I followed her into the garden of tranquillity fearing that the some of the inter-dimensional forces might not be quite in balance. I was not wrong.

“Look what he has done. So far I have paid that idiot 300€ for this.”

The wall was a roughly vertical pile of bricks, which began at the steps and meandered across the garden like a drunk’s footsteps. It followed the contours of the ground beneath it exactly, showing no need for any form of horizontal linearity or vertical order. Before it got to the far wall, it fell over and lay comatose on its side having given up all hope of being a wall, and was content to sleep it off till another day. I felt sorry for Pauline having to pay for this disaster.

“I will come along in the morning and straighten it out Pauline,” I said. “It won’t take long.”

The next morning I brought a few tools and began scraping cement off the bricks. In actual fact there had been no need to rush because there was not enough cement in the sand for it to be called mortar; it would never have set anyway. That was when Geordie arrived with Loveless.

I slipped out of the garden to mix some real cement whilst a conversation developed within the Zen Garden between Pauline and Geordie. Moments later I returned with a full bucket, and as I laid anew the cleaned bricks from Geordie’s attempt at bricklaying, I listened to the conversation.

“You must understand that this work is labour intensive and the hours I spend are for your ultimate benefit,” Geordie said. “I can’t rush in case I make a mistake and waste your time and money.”

“I would hate to see one of your mistakes if this is an example of you getting it right. The whole bloody wall is a mistake. Hiring you was a mistake,” Pauline’s voice was becoming more strident. “Look at it. It’s just a pile of rubbish that I have paid 300€ for!” Geordie had walled himself into a corner, and for a moment, his eyes showed his panic, but then his true nature asserted itself.

“The wall was not like this when I left it yesterday … there must have been an earthquake in the night!”

For a few seconds there was a silence you could cut with a trowel. I spread my feet in anticipation of the aftershock, and watched its rapid approach on Pauline’s face.

“You idiot! Do you think I am going to believe that!” she pointed at me. “Do as he says and don’t open your mouth again.”

I unravelled my line-band and pinned it to one end of the wall with a heavy stone. I did the same to the other end, but only after moment of thought. I already had the hand patted prayer laden foundations, but they were aligned to universal forces, whereas my line-band only showed the shortest distance between two points. Finding a mean was difficult because there was no obvious general direction. In the end I chose the line of least work. The wall would not be at right angles to the rest of the garden, but it would be straight. Whilst I was doing this Pauline had seen my use of the line-band and asked Geordie why he had not used one.

“Oh I have one.” Geordie glibly answered, unaware that he had just put his foot on a mine.

“Well why the bloody hell didn’t you use it!” Pauline shouted at the top of her voice. Geordie recognised defeat and was silent. At this point, I revealed my other secret weapon; a spirit level. Pauline fell on Geordie like a ton of bricks.

“Why didn’t you use a level?” she snapped. “In three day’s work I have never seen you use a level.”

“Yes I did,” blurted Geordie. “I used my bottle of water!”

“How can you use a bottle of water as a level?” Pauline barked. My ears came up too. This was a new one on me.

“The bottle of water has a bubble in it. Lay it on the wall on its side and you have a level.” Pauline gasped at this revelation. I did too.

“Then why is your wall not level? Pauline asked quietly.”

“Well it was a warm day, so we drank all the water in the bottle,” Loveless explained before Geordie could invent an answer.

Pauline was speechless with anger. She turned and stormed into the house.

“Maybe you should have taken more notice of the spirit level than the spirit guide Geordie.” I added. “Why don’t you help Loveless mix some cement.”

I had to turn away. Laughing out loud would not have helped the situation. Geordie strutted down the path, and left the garden of tranquillity.

I had the feeling that in future years Pauline would be far from tranquil in her garden when she thought of how much she had paid for this little wall. After a couple of hours, I had restored some semblance of linearity to the wall and was filling in the hollows where its original course had followed a power vortex instead of a piece of string. Pauline had by now calmed down. She came and looked at the new wall.

“I can cement render it tomorrow if you wish.” I told Pauline.

“No thank you. I am going to get a Spanish builder to finish everything off. But thanks for helping me.” Geordie’s face dropped.

“I can finish the work now,” he offered.

Pauline walked up to Geordie and stood inches from his face.

“In two hours he has done correctly what took you three days to do wrong. Get out of my garden and don’t ever set foot in it again,” she hissed.

I gathered up my tools whilst Geordie told Loveless to pick up his. We left the Zen Garden and went our separate ways. Call me evil, but I could not resist calling over my shoulder to the master of unseen forces and his acolyte.

“See you later Geordie, and watch out for earthquakes on the way home pet.”

0

Like

Published at 1:07 PM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 1:07 PM Comments (0)

The Journey home

Friday, December 17, 2021

By the 31st of December Columbus had decided that he should load provisions and water aboard the Niña. He was still receiving promises of more gold from the Cacique, and he would have liked to explore more down the coast to find the source of the metal, but he wrote that he was wary of another accident that could make the Niña incapable of the return journey. He had met cordially with several native Caciques and had received gold as gifts, and he urged the men who were to remain behind at fort Navidad to obtain as much gold as they could for their return from Spain. It was during one of these meetings that a native from further along the coast to the east reported having seen the Pinta. This news added another dimension to Columbus' worries. There were now two expeditions; the one that he led, and the one led by Pinzón.

In order to give the natives a show of force, he took the king and some of his advisors out in the Niña and fired one of the lombards at the hull of the Santa Maria. They were suitably impressed when the ball went straight through the ship and a good way beyond. He writes that he hoped that the natives would see that his men were friends and would defend them in case of attack from a nearby tribe called the Caribs, who the natives feared.

He began to organise the provisions for those who were to remain. Most were volunteers. Along this coast Columbus’ small flotilla had seen nothing but good nature and friendship from the natives. He left Diego de Arana, a native of Cordoba and Pedro Gutierrez, "repostero de estrado" of the King and Rodrigo de Escovedo, a native of Segovia. He gave them all the powers which he had received from the sovereigns in Castile. The officials supplied by Isabel, the escribano and alguacil also elected to stay. He left them seeds for sowing and a ship's carpenter and calker, a good gunner “who knows a great deal about engines” and a cooper and a physician and a tailor, and all, he says, are seamen. He left them biscuit sufficient for a year and wine and much artillery and the ship's boat in order that they, as they were most of them sailors, could go to discover the mine of gold when they should see that the time was favourable.

Columbus left 39 men behind at La Villa de Navidad on the 22nd January 1493. He had no alternative to leaving good crewman behind whilst he was obliged to sail with people that he did not trust.

He first had to navigate seas to the east of Española (Haiti) which were full of reefs and sandbanks, and Columbus carefully picked his way through them. He sent a sailor to climb the rigging around the main mast and watch the sea ahead for dangers. It was in the afternoon of the 6th that the lookout called that he had seen the Pinta ahead. With nowhere safe to anchor, the two ships returned to the coast at a place they had called Monte Christi.

When they finally met Martin Alonso Pinzon, the captain of the Pinta, he was full of apologies saying that he was forced by circumstances beyond his control to leave the other ships behind. The natives on his ship had led him on a wild-goose-chase from island to island looking for gold. Columbus wrote that he believed none of it, and another account says:

“(they) had not obeyed and did not obey his commands, but rather had done and said many unmerited things in opposition to him, and as Martin Alonso had left him from November 21st to January 6th without cause or reason but from disobedience: and all this the Admiral had suffered in silence, in order to finish his voyage successfully” The account continues, “he decided to return with the greatest possible haste and not stop longer.”

On the 9th, whilst they were anchored in the mouth of a river at Monte Christi, Columbus ordered the ships to sail upriver to fill the water butts on both ships with fresh water for the voyage home. While they were filling the water butts, his sailors were amazed to see that the sand of the river was full of grains of gold. When they brought the barrels aboard they found that the gaps between the staves and the hoops were full of gold dust. He had found the source of the gold just 20 leagues from La Villa de Navidad, but the crews both ships now knew where it was, and the stakes in this great gamble had just got higher. Columbus writes:

“That he would not take the said sand which contained so much gold, since their Highnesses had it all in their possession and at the door of their village of La Navidad; but that he wished to come at full speed to bring them the news, and to rid himself of the bad company which he had, and that he had always said they were a disobedient people.”

Around 12th January, they left the coast behind and struck out across the Atlantic. The two ships stayed in formation for four weeks making poor headway, but on 13th February ran into a storm. For three hours the two ships tried to hold their easterly course, but finally they had to turn and run west before the force of the gale. During the night, the ships became separated and the Niña spent the rest of the next day going west. The Niña was not handling well in the storm because the ballast of the ship was wrong, and Columbus ordered the crew to fill the empty drinking-water and provision barrels in the hold with sea water to try and stabilise the ship.

At the height of the storm Columbus called the crew to prayer and he ordered as many dried peas as there were crewmen to be brought from the provisions. He marked one with a knife and put them all in a hat. They drew lots four times and he made the crew vow that if they survived the voyage whoever picked the marked peas would make the pilgrimages to four different shrines in Spain and that the first land they would all go in procession in their shirts to pray under the invocation of Our Lady. In secret, he wrote a declaraion about all that he had discovered and wrapped it in a wax cloth with a letter asking whoever found it to return it to the King and Queen of España so that: “The Sovereigns might have information about his voyage.” He ordered that a barrel be brought to his cabin and he sealed the parcel within and threw it overboard.

On the morning of the 15th February the skies brightened from the west and they saw an island on the horizon. It took them all day to reach it, but they could find no harbour and so they dropped anchor on the lee side of the island. In the night the anchor was torn away, and the Niña had to beat about to hold position. The following morning they dropped a second anchor and sent the small boat ashore where his sailors learned it was the island of Santa Maria, one of the islands of the Azores. That evening, Juan de Castaneda, the governor of the island, sent men to the beach with fowls and fresh bread. Castaneda apologised for not coming himself, but that in the morning he would bring more refreshments. In thanks for their deliverance from the storm, Columbus allowed half the crew to go ashore and fulfil the vows they made. They asked the islanders there to send a priest to say mass for them in a small hermitage further along the coast.

Columbus had forgotten that the King of Portugal had put a price on his head before the voyage, but now they had returned safely after discovering a New World, there was a bigger price offered for their capture and the safe delivery of the knowledge they carried in their heads; and the Azores were Portuguese territory.

Whilst the crew prayed they were surrounded by armed villagers. Columbus waited for them to return, then fearing the worst, he sailed around the coast to where he could see the hermitage. The governor of the island was there with armed soldiers and he was rowed out to the Niña in the small boat. Columbus tried to entice them aboard, but the governor was too wily to be captured. Even with half of them held on the island, the Niña still had had sufficient crew to continue her return voyage to Spain. He held up the letters from Isabel and Ferdinand and promised retribution against Portugal from España unless his men were returned. The governor yelled that he did not recognise the kingdom of España; he was duty bound to follow the orders of the King of Portugal.

Columbus realised that he was wasting his time, and since the wind was against him he ordered that running repairs be made to the ship which was taking on water. He had already lost one anchor and was not about to lose any more either to sabotage or storm. The weather was worsening and he set sail for the nearby island of San Miguel, but the seas became so rough that he was forced to return to Santa Maria. On the 22nd they anchored in the lee of the island and a messenger asked if Columbus would allow two priests and an escribano (notary) aboard to examine his papers of authority. They were allowed aboard and given every respect as they studied the letters signed by Isabel and Ferdinand. Finally, after conferring in whispers, they told Columbus that his men would be returned. Columbus had successfully called the governor's bluff, and his men rowed out to take their place on the Niña once more.

Picture; Alan Pearson, alanpearson.pixels.com

On Sunday 24th February the wind eased and came around to a direction which would take the Niña back to Spain. Columbus immediately put on all sail and left the Azores behind. All went well for three days before what could have been a tornado battered the tiny ship and split her sails. By March 4th the storm still had not abated, but the dawn brought the sight of land and many of his sailors recognised the Rock of Cintra to the north of the port of Lisbon. At the mouth of the river Tagus was the small village of Cascaes, and the villagers had watched the Niña’s approach through the storm and had gone to the church and prayed for the safe return of this tiny vessel. Their prayers were answered, and Columbus docked his ship at Rastelo within the bay of Lisbon, where he learned that 25 ships had been lost in the storm, and many more had been tied-up in Lisbon waiting for the storm to pass. There was no news at all of the Pinta.

But the storm was not over for Columbus. He was still in hostile Portugal, and the flagship of the Portuguese navy was also tied up in Rastelo waiting for the storm to pass. Columbus noted that; “She was better furnished with artillery and arms than any ship he ever saw.” On March 5th her captain and financial patron, Bartholomew Diaz, sent an armed party to the Niña to demand that Columbus come to his ship and give an account of himself. Columbus wisely refused. The reply came back that he could send the master of the Niña in his stead. Columbus again refused. No member of his crew would leave his ship to be held hostage.

Realising that he was on a knife edge, where any aggression would result in a war with España, Diaz asked to see the letters of free passage given by Isabel and Ferdinand. Columbus agreed, and after reading the letters he sent his captain, Alvaro Dama, who arrived, “In great state with kettle-drums and trumpets and pipes” and put himself and his crew at the disposal of the admiral. All of Lisbon had heard of the discovery and wanted to see Columbus and the natives of the Indies, and for the next three days they were inundated with visitors and dignitaries. He was invited to visit the King of Portugal who was at the valley of Paraiso, nine leagues from Lisbon and he was entertained and recieved “many honours and favours”.

Finally, at 8 o'clock on March 13th Columbus raised the anchors and set sail to return to España. Two days later at sunrise he was off the sandbar at Saltes, Huelva, and when the tide turned at mid-day, he sailed upriver and tied up the Niña at the same dock that she had left on August 3rd the year before.

Pinzón and the Pinta had missed the Azores and arrived at the port of Bayona in northern Spain. After a stop to repair the damaged ship, the Pinta limped into Palos just hours after the Niña. Pinzón had expected to be proclaimed a hero, but the honour had already been given to Columbus. Pinzón died a few days later.

0

Like

Published at 9:41 AM Comments (0)

0

Like

Published at 9:41 AM Comments (0)

The Christmas day disaster.

Friday, December 10, 2021

By the 25th according to his log, Columbus had not slept for 48 hours. The coast here was full of sandbanks or rocks, and to approach the shore was dangerous. This is where there is some controversy over what is recorded in the log. The Captain of the Santa Maria was Juan de la Cosa, but throughout the exploration of the islands and accounts of meeting the natives, Juan de la Cosa is never mentioned. As captain, de la Cosa would not have to stand watches, he had capable crewman who understood the complexities of sailing his boat. There was a hierarchy of trusted and proven friends which had been built up over a number of years. It was essential that a seagoing ship should have men who could be trusted to sail the ship safely whilst others slept. So why was Columbus having to stay awake?

Both ships were in a bay that Columbus had explored the previous Sunday from the rowing boat that was stored on deck and used to go ashore. There was an open passage that extended from deep water to the beach, but bounded on both sides by sandbanks and reefs. There was no wind, and the sea state was described as in a "porringer”, (bowl) or calm. According to what was written in the log, at eleven o’clock in the evening the admiral went to his bunk to sleep, leaving a sailor at the helm. The rest of the crew also were sleeping when the sailor on watch handed the helm to the cabin boy and went to his own bunk.

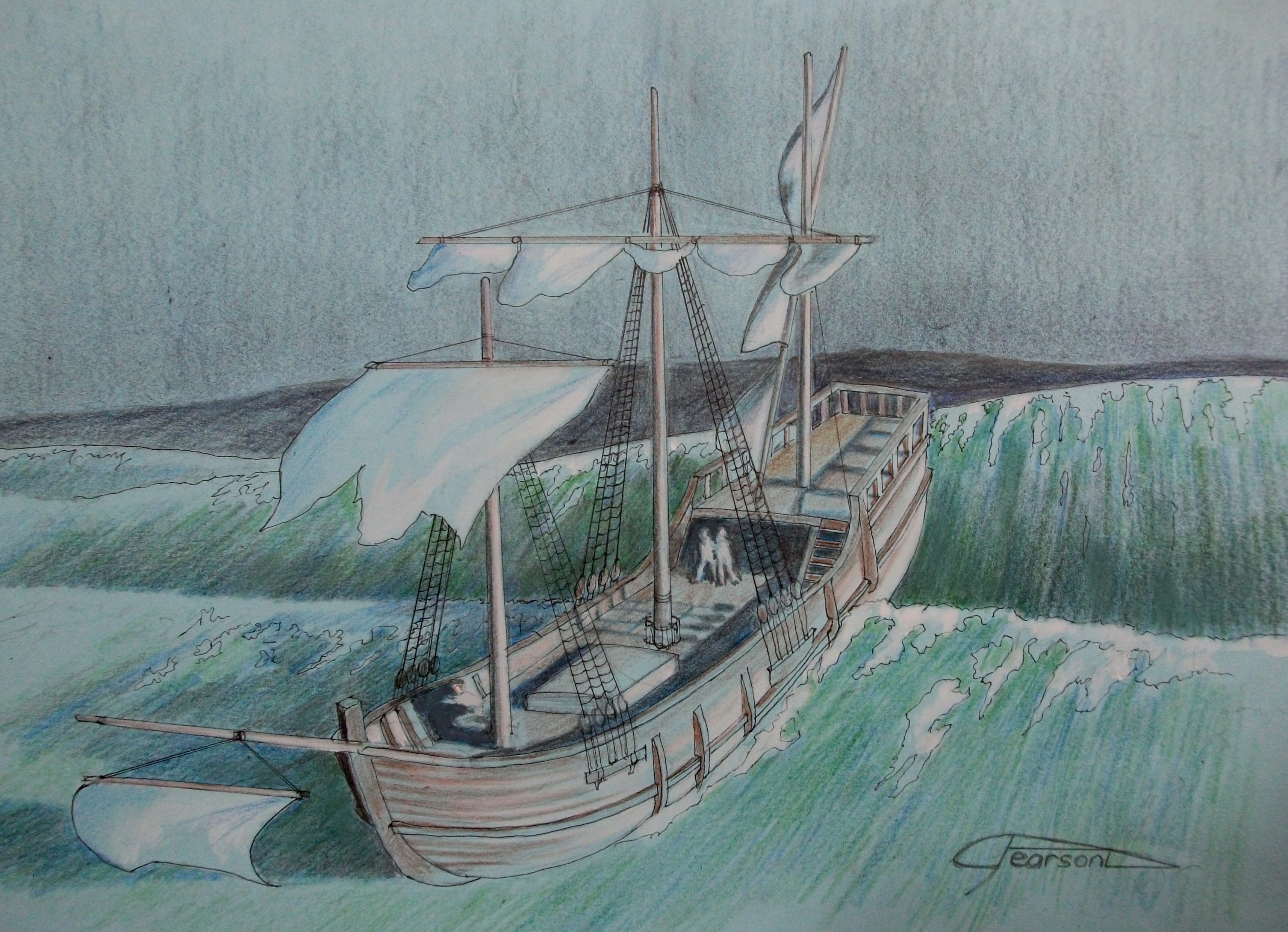

Let me show you what the helm of the Santa Maria looked like.

This is not the wheel with handles and ropes that turned the rudder in bigger ships. The rudder of the Santa Maria probably weighed well over a hundred kilos and was operated by a ten foot tiller. It was operated from two decks below the stern forecastle, where the captain had an unrestricted view of the ship and its surroundings. Between the two decks was the captain’s cabin. To steer the ship required at least two people, one on the stern forecastle who could see where they were going, and the other, two decks below to push the rudder in the required direction. To imagine that a ten-year-old boy could control the ship alone, even in a dead calm, is folly. But at night, when there are no lookouts, is criminal. Something was badly wrong. Where was the chain of command? Where were the leading officers who had spent years at sea and knew the rules and risks.

The poor cabin boy raises the alarm as the ship gently runs aground on a sandbank. In the near distance is the sound of breaking waves on a reef or shore. Columbus feels the change in the motion of the ship and immediately wakes from his sleep and runs up to the forecastle to take command. Columbus’ log then says that the master of the watch came out, and Columbus orders him to launch the rowing boat and take an anchor and cast it at a distance from the stern of the Maria. The anchor line would then be put around the capstan and the crew could wind the Maria off the sandbank.

Who “the master of the watch” was is not clear, but it has to be Juan de la Cosa.

Columbus does not mention him by name in his logs, but other later accounts say that a blazing row developed on what to do next. De la Cosa would be pretty upset that his ship had been allowed to run aground, but seemingly he insists that they must abandon ship and go to the Niña, which was “half a league to windward”. Columbus accuses him of treason and desertion in the face of danger, serious charges for which others have received the death penalty. Judging by the language in the log you would expect some sort of court martial or attempted court martial at home afterward, but no such thing is recorded, and Juan de la Cosa is never mentioned by name. Nevertheless, the boat is launched, but the men in the boat led by the “master” rowed to the Niña.

The captain of the Niña rightly refused to allow them aboard and ordered them to return to the Maria. All this must have taken a couple of hours, meanwhile the tide was falling, and the pressure on the Maria’s hull was focused on one point, and the hull timbers were bending. If the caulking between the hull planks gave way, the sea would flood in. Columbus ordered that the mast be cut down and all excess weight be thrown overboard to lighten the ship and re-float her. There was no terrible storm, just the inexorable retreat of the ocean, and finally, the hull planks gave way between the ribs, and the sea filled the hold of the Santa Maria. Columbus could not save his flagship; it was too far from the shore for the crew to swim, and so they were ferried to the Niña in the rowing boat. The Niña spent the rest of the night using whatever wind there was to stay away from shallow water. At dawn, the small boat set out for the shore with Diego de Arana, of Cordoba, Alguacil of the fleet, and Pedro Gutierrez, "repostero" of the Royal House, to find the Cacique who had invited Columbus to bring his ships to his harbour the previous Saturday.

When the Spanish dignitaries explained what had happened to the Cacique he wept. Within an hour he had organised the people of the village to take “many large canoes” and help Columbus unload the Maria and salvage whatever they could. In his log Columbus says that they unloaded the Maria with great assiduity and ensured that whatever was unloaded and carried to the shore was done so without pilfering. The Cacique set aside several houses in which to store any valuables and placed guards around them at night. The whole village was openly distraught at the plight of the Spanish. Columbus is moved enough to write in the notes that he intends to show Queen Isabel and King Fernando that:

“They are an affectionate people and free from avarice and agreeable in everything, and I certify to your Highnesses that in all the world I do not believe there is a better people or a better country: they love their neighbours as themselves and they have the softest and gentlest speech in the world and are always laughing. They go naked, men and women, as their mothers gave them birth. But your Highnesses may believe that they have very good customs among themselves and the King maintains a most wonderful state, and everything takes place in such an appropriate and well-ordered manner that it is a pleasure to see it all.”

Natives began to arrive in their canoes from further up the coast bringing gold, which they were more than willing to trade for hawk’s bells. The Cacique invited Columbus to eat with him, and he writes that he was very impressed with the king’s table manners and cleanliness, and that after eating they rubbed their hands with certain leaves to clean them. Columbus gave the king a shirt and gloves which impressed him so much that he wore them continuously, and after the meal Columbus gave a display of a Turkish bow and arrow that he had ordered brought form the Niña. The natives had no knowledge of the weapon, and were impressed with the iron arrowhead. Columbus was quick to note that they had never seen iron or copper before, and the steel of their swords was a source of constant amazement.

Painting: Alan Pearson. alanpearson.pixels.com

It was obvious to all that they could not all go back to Spain on the Niña, and Columbus ordered that the Maria be cut up to build a stockade near the native village where he can store the weapons and cannons so that they don’t fall into the hands of the natives. Half the crew of the Santa Maria dismembered their ship and floated all the timber to the beach. They left the hull where it was, but everything else was brought ashore where the other half of the crew were building the stockade which Columbus named Fort Navidad. He writes: “And it is quite true that many of the people who are here have begged me that I would give them permission to remain. Now I have ordered a tower and fortress constructed and all in a very good manner and a large cellar.”

But in in his private log, Columbus bleakly writes:

“Had it not been for the treachery of the Master and of the people, who were all or most of them from his country, in not wishing to cast the anchor at the stern to draw the ship off as the Admiral ordered them to do, that the ship would have been saved.” He continues, “And the taking of such a ship he says was due to the people of Palos, who did not fulfil what the King and Queen had promised him, that is that he should he given ships suitable for that journey, and they did not do it.”

He discharges his culpability in the loss of the Santa Maria with the words “of all there was in the ship not a leather strap was lost, nor a board nor a nail, because the ship remained as sound as when she started except that she was chopped and split some in order to take out the butts and all the merchandise.”

But the real problem was still there in the form of a crew that constantly disobeyed his orders, and a little later in his diary he fumes: “I will not suffer the deeds of evil-disposed persons, with little worth, who, without respect for him to whom they owe their positions, presume to set up their own wills with little ceremony.”

Much of the cargo that he wanted to take back to Castile had been loaded onto the Niña, and now he had to choose who was to be left behind. The only blessing that Columbus could count on was the generosity of the natives in helping him deal with the loss of his flagship. They had promised to “cover him in gold” before his departure.

But gold is the colour of greed and treachery. Facing him now was the very frightening prospect of crossing the Atlantic with a mutinous crew who knew where the New World and its gold was, could speak its language and did not need this jumped-up “Admiral of the Ocean” to take all the glory.

1

Like

Published at 10:55 AM Comments (0)

1

Like

Published at 10:55 AM Comments (0)

Too good to be true

Friday, December 3, 2021

With the Pinta gone gold hunting alone, Columbus had to spend a frustrating two days at anchor whilst the wind was against them. The wind finally came round to a more favourable direction, and after sailing down the coast of Cuba, Columbus crossed the Windward Passage to the island now known as of Hispaniola. For the Santa Maria the passage was slow, but Vicente Yáñez Pinzón on the Niña was making good speed and went ahead to look for a safe harbour before night fell. Vicente showed a light so that Columbus could follow, but the admiral was unsure and decided to wait until daylight before he entered the harbour.

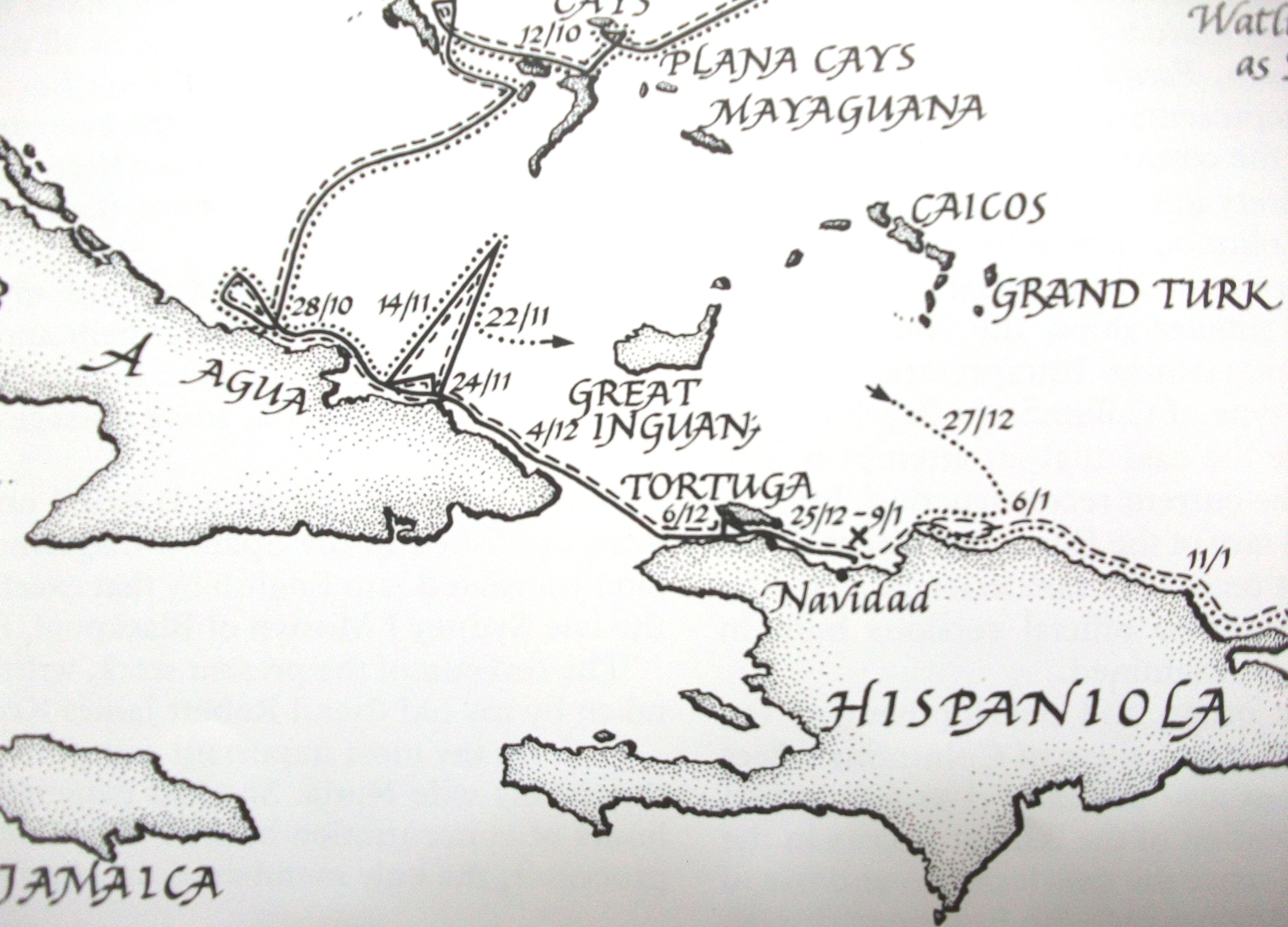

Map; XavierPastor Map; XavierPastor

On 6 December the Santa Maria anchored in what turned out to be an excellent natural harbour which he named Puerto Maria. There were several smaller neighbouring islands, and that night on an island to the east, which he had named Tortuga, he saw campfires and the next day columns of smoke. The natives with him said that they called this larger island Bohio. There were no signs of natives here and so he decided to sail further along the coast, and over the next couple of days the crews on both ships caught some of the abundant fish to supplement their meagre rations.

He called the new island Española, and though the natives had fled, there was plenty of evidence of their existence. During the night they had seen fires and the sharp eyed among the crew had seen what looked like watch towers on high points of the island. The natives were still elusive, but the crews caught glimpses of them as they abandoned their canoes on the beach and fled into the forests.

During the 10th and 11th the skies were grey and the wind blew from the north-east, causing the small ships to drag their anchors. With no more exploring by sea possible, Columbus ordered six well-armed men to go ashore and see if they could make contact with the natives. They returned with descriptions of wide tracks, but just a few wooden huts. The natives on his ships were becoming more insistent that they wanted to be returned home and set free. They told Columbus that these islands were inhabited by cannibals because when they captured people they were never seen again. Columbus took this to mean that a superior powerful empire had been conducting slaving raids on these peaceful, hapless people. This empire could only be the Great Khan of China.

His mind was now focused on finding the source of the gold that he had seen the natives use for trinkets. Gold had been his promise to Isabel and Ferdinand, and no amount of spices would make up for the lack of it.

The wind was still holding them at anchor on the 12th and Columbus once again ordered armed men ashore to try to find indigenous natives, but this time he sent some of his captured natives with them. His men planted a wooden cross on the rocky shore and struck off inland. Before long they found a village, but the natives fled and only one young, beautiful, girl was left behind. Columbus’ natives talked to her and brought her back to the ship where she was given clothes and food and sat with the other native women, who convinced her that the Spaniards were not bad people. Columbus allowed her to return to the shore and sent three men with her. They returned after midnight saying that they had travelled several leagues inland and were afraid to accompany her any further. The next morning he sent nine more armed men and a native to follow the route taken by the girl.

The found a wide valley which had been cultivated and a village of possibly three thousand people, but totally deserted. After calling to them their native managed to persuade some to come out of hiding. After more calming words, and seeing that the Spanish were not hostile, the natives flooded back to the village. Columbus writes that many of the natives were shaking with fear as they returned to their houses. Once it was clear that the Spaniards meant no harm they showered them with presents. Despite all the shows of friendliness, the Spaniards saw no gold ornaments or jewellery.

The two ships crossed to the island of Tortuga, but the contrary wind kept them from landing. They saw houses, but the natives there, too, had fled, and so they returned to Española. Over the next few days they made several trips to Tortuga with little success and were forced to return to Española where they had made friendly contact with the natives. On the 16th they came across a native alone in a canoe crossing the straits in heavy weather and took him and his canoe aboard. They landed him on Española close to a village and allowed him to paddle ashore.

Picture; Alan Pearson. alanpearson.pixels.com

Within hours around 500 natives had filled the beach, and they paddled out to the anchored ships in their canoes. They brought no gifts, but the Spanish crewmen noted that they had gold piercings in their ears and noses. Columbus ordered that the natives were to be treated honourably and not exploited for their gold jewellery. Shortly afterwards, their king appeared on the beach, a young man of about twenty years, who was surrounded by councillors and advisors. One of Columbus’ natives spoke with him and explained that the Spaniards had come from heaven and were in search of gold.

He told the king that they were going to the island of Beneque where they had been led to believe there was much gold. The king wished them well and offered his help, but Columbus later wrote that when he told him that he served a higher king and queen in Spain, the king was under the impression that they were in heaven and not of this world. Columbus thought it best not to press this point. He writes later that the natives were so naïve and placid that they would be easy to subjugate and convert to Christianity, which was one of Isabel’s conditions for funding the voyage.

Now all he needed was the gold.

Some of his crewman were becoming fluent in the native language, and he sent them to trade with the Indians for their gold. They met with a man called Cacique, whom they took to be of some standing in the area. He was offered glass beads for a piece of beaten gold as large as a hand, and when they had agreed the deal, the Spaniards asked if he had any more gold. Cacique told them that he would return the next day with more of the metal. But the next day, instead of gold, Cacique brought 40 men, and put on a show of his displeasure. Columbus made signs to placate Cacique and finally the men that he had brought climbed into their canoe and left. After this strange turn of events Columbus felt that there was no more gold to be had on Española or Tortuga and decided to press on to Beneque. He had been told that the island was four days’ journey by canoe, which he estimated to be 30 or 40 leagues, a distance that his ships could cover in a single day with favourable winds.

However, the next day the wind was not very favourable at all, and either dropped or was against them. The ships were anchored some distance from the beach, and Columbus was still hoping that Cacique would bring more gold. He had sent some men inland to scout, and he was eating in the forecastle when they returned. The brought with them the king, who was carried on a litter and accompanied by around 200 villagers. The king came aboard, and when he saw that Columbus was eating, he promptly sat at the table with him and the Admiral offered him some of his food. Many of the villagers scrambled over the side and swarmed over the decks marvelling at the strange ship and its crew, who were becoming alarmed. When the king saw this, he ordered them all ashore again except for two older advisors who sat at the king’s feet. Columbus ordered food to be brought for them all. The king left just before nightfall and was carried in his litter up the beach into the forest.

Over the next few days, wind permitting, they sailed along the coast and wherever they stopped they were greeted by natives, who after initial trepidation, offered them food and gifts. There was little gold to trade, but whenever they could trade it for trinkets they did, and some of Columbus’ men were getting greedy. He ordered them to always give the natives good payment for their gold, after all, they were only giving them worthless trinkets. Word of the Spaniards love of gold had spread before them as they moved from bay to bay along the coast, and the natives came from further afield in their canoes and followed the ships. By now they had realised that the name Cacique meant king or dignitary, and was a title. By 24 December Columbus had been invited to meet other Caciques further along the coast, always with the promise of gold. Apart from the disappearance of the Pinta, things were going extremely well.

0

Like

Published at 10:00 AM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 10:00 AM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|