The Cheery Cobblers of Ronda

Thursday, January 25, 2024

Ronda's cheery cobblers, Jaime, Miguel and Ismael Becerra. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Is it only me, or have you also noticed that everything lasts a shorter and shorter time? Be it mobiles that are virtually useless after a couple of years, computers that refuse to update, self-parking cars that go wild, or clothes and shoes that barely last a season - it looks like the disposable culture that we should have put behind us a long time ago, is here to stay. For this reason, I was glad to discover that some trades that have disappeared in many other countries, still prosper here in Spain.

Take their friendly shoemakers …

Jaime fixing a pair of boots with a smile. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When we lived in Vancouver, British Columbia, our Chinese shoemaker made it very clear that my French leather boots were long past their prime and impossible to fix. However, since these were my favourite boots of all time, I still brought them with me when we moved to Spain. And here in our small mountain town, the shoemaker took them in with no reservations whatsoever. He added a new sole, stitched them up, and polished them so that they lasted for another three winters, all for the price of four pairs of shoelaces!

Shoeforms. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Cobblers or zapateros in Spanish is one of the oldest professions in the world. It is also a dying trade and a disappearing art in many Western countries, where we have become accustomed to buying a new item when something falls apart. It is increasingly more difficult to find someone capable of - and willing to - fix something as ‘degradable’ as used footwear. But at least here, the cobbler trade is well-regarded. Although Ronda has barely 34,000 inhabitants, there are three Zapateros that I know of in our town, and all run an industrious business with a bit of bag repair and belt sales on the side.

Sign. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Everything can be fixed

Our shoemaker, Zapatería Becerra, is a family business started by Miguel Becerra Aguilar (63) 40 years ago, and judging by the row of waiting customers, he won’t be retiring any time soon. The business has only increased, and his sons Jaime (42) and Ismael (34) started working with him after they finished senior high school. Today they have children of their own, and while both express hopes that their offspring will study instead of joining the family firm, they assure me that they enjoy their work. The only drawback is that they never have a single moment to sit down.

Ismael fixing a hiking boot. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Every time I have been to the Zapatería, including a couple of times I came by to interview them in their two-second break between clients, there has been a line-up. People bring old shoes, boots, sandals, stilettoes or slippers that need fixing, dyeing, and polishing, brand new shoes that need expanding, belts and watch straps needing extra holes or a new buckle and handbags, backpacks, suitcases and jackets with broken zippers or lacking Snap-on buttons, not to mention keys to be copied. The Becerra boys can fix virtually anything!

Using stitching machine from 1865. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Just for the last task, they have a row of seven machines that represent the technical evolution of key-copying from the middle of the last Century. The most valued antique in the shop is a curious sewing machine from 1865, and the oldest key-cutting machine with a very cool built-in lamp was the first that Miguel invested in when he opened the shop in 1984, and although he has the latest in laser cutting technology, it is still his preferred tool for the task.

Miguel makes keys with the oldest and most dependable of his seven machines. Photo © Karethe Linaae

From baker to shoemaker

Miguel started working as a baker in the family’s bakery in the 1970s when he was a teenager. The Panadería which today is run by his cousin, is still so famous for its bread that the waiting customers spill onto the sidewalk. But Miguel didn’t enjoy working through the night as most bakers do and decided to become a shoemaker instead. He knew nothing about the trade and had no equipment, but gradually he learned and started his workshop across the street from their present location.

Metal lasts. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When I ask the sons how they learned the cobbler trade, they tell me that the only way to master the profession is to do it. “Everything we know, Dad taught us”, they agree. Jaime admits that he once had a dream of joining the police or the army, and Ismael says that if he ever changed job, it would have to be to become a bureaucrat with a generous salary, a big desk and very little to do. But none of them regret their choice and both smile while they hammer and patch and sew and glue until the sweat is pouring.

Jaime at the polishing machine. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Jaime at the polishing machine. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Service with a smile

The entire family is a friendly lot and I ask them if they always are this happy.

«Well, our smiles aren’t glued on», Miguel winks and admits that there are certain days and a few customers that try even the endless patience of the Becerras. But generally, the clients are nice, and Miguel cannot recall having had a single complaint in all the years they have run the business. And why should they? The team works ceaselessly from when their doors open at 09.30 until 20.00 at night, except for a couple of hours siesta break. Around 150 customers walk in and out every day and the master cobbler calculates that if all three are at it, they can fix 60 pairs of shoes in a day, in addition to a slew of zippers and keys and what have you not …

Ismael can fix anything. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Most clients are told that they can come back and pick up the repairs already that same afternoon or the next morning - that is if they don’t fix it for you there and then. «We try to repair everything the same day we get it in», Miguel says and adds that jobs are paid when they are picked up.

Miguel adding a snap-on button to a jacket. Photo © Karethe Linaae

With such rapid rotation, one would think that there are hardly any repairs sitting waiting to be picked up. And one would also assume that they dispose of unclaimed goods after a couple of months. That is a common business practice, no? But I could not be more wrong. Jaime shows me rows upon rows of shoes from what he calls the ‘pre-pandemic era’ that soon will have been left for five years. All are fixed, polished, and ready to go. With an average bill of let's say 10 euros a pop, they are sitting on an entire fortune of abandoned shoes.

Under pressure. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I ask how they can keep track of the hundreds of shoes that people bring into the shop, particularly when all they ask for is people's first names which are written on a Post-it note and attached to the insole of the shoe. Miguel admits that they aren’t fully digitised yet, but they have a system that functions well by separating women’s and men’s shoes and ordering them by the date they were brought in. In addition, they know almost all their clients by their name - or by their footwear.

Dangling shoes. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Miguel remembers only once a man came in to pick up a pair of shoes that they couldn’t find. They searched high and low, but the shoes had vanished. The man called his wife who happened to be at the hairdresser’s next door to tell her that her shoes were gone. She immediately reprimanded him, saying that it wasn’t a pair of shoes that he was supposed to pick up. It was a pair of scissors!

I should have guessed. Of course, the shoemakers also sharpen knives and scissors on top of everything else they do. To me, the zapateros are an important Spanish cultural institution, and without them, Spain would simply not be the same.

Stitching machine from 1865. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 5:44 PM Comments (3)

2

Like

Published at 5:44 PM Comments (3)

Am I just Vintage or completely Obsolete?

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Grandma's fountain pen. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The turn of a year makes one particularly aware of dates and numbers. We might not remember what we did on the 7th of August, but most of us know exactly where we were on New Year's Eve and what our thoughts were about the coming year. A new year tells us how incredibly fast time flies, and for us of a certain age, reminds us that our New Year's celebrations and years are counted. With January comes taxes, annual fees, and updates of electrical systems of mobiles and computers. And that is in fact what I wanted to talk about– computers.

The other day I had to call Apple Care, Mac’s technical customer service for products that are under their warranty. As with everything in life, none of these warranties lasts forever, though one can purchase an extension of the manufacturer guarantee to a total of four years. My old desktop, which will be nine years old sometime in 2024, is therefore far beyond the warranty period, but thankfully my sleek little laptop is still covered. In the past, nine years used to be nothing for Apple (and this is not an ad for them!). The old Macs were like the Volvos of bygone years, which drove faithfully for decades, even with several hundred thousand kilometres behind the wheel. They were practically indestructible.

But let’s get back to the warranties. Since my desktop computer had started protesting and giving me blank stares if I had more than two programs going simultaneously, I wanted to transfer my enormous photo archive to my laptop. After several failed attempts, I decided to call Apple’s technical helpline. This means double waiting in Spain, as I insist on talking to their English-speaking customer support, who likely sits in Uttar Pradesh.

Once I got a live person on the line, I explained the issue to the technician who immediately said that she had to talk to her supervisor. The reason for this was that my computer was so old that it was what they called Vintage. I was fortunate as the machine was not yet old enough to be considered Obsolete, she added gleefully. If that had been the case, they would not be able to do anything for me and my ‘antique’.

Let’s leave the technician for a while, while we go back to the theme of vintage, as the techie’s comment got me thinking. To me, the expression vintage refers to post-WW2 style clothes, American music from the 60s, and modern classic Danish furniture from the 1970s. In other words, it brings my thoughts to the baby boomers and their gear. Therefore, I had not expected to hear that my Mac from 2015 was in any way vintage.

The rapid expiry date of technical products these days is of course not only an issue with computers, as it is much worse with mobile phones, where just a handful of years makes them practically useless. But if a computer that is barely a decade old, is obsolete, then what am I?

With different operating systems and what have you, my technical conundrum has not yet been solved. However, it made me realise something. Whatever they say about stuff being obsolete, is not always true. At least this expired, out-of-stock model is still alive and kicking. May all of us who are defined as Vintage and Obsolete, live long past our official best-before dates.

Mindfulness before all. Photo © Karethe Linaae

1

Like

Published at 2:51 PM Comments (4)

1

Like

Published at 2:51 PM Comments (4)

MY FIRST PISADA Andalusian grape stomping in the 21.st Century

Friday, October 20, 2023

Grape stomping is not for wimps. Photo © Jaime Barrera

You might have seen one of the movie history’s most-known comedy clips with Lucille Ball stepping on wine grapes. In the black and white recording from 1956, she dances around in an enormous barrel on a fictional Italian farm. But the vintage clip refers to a tradition that goes back thousands of years, and which thankfully still is kept alive here in Andalucía.

When our friend and vineyard owner, Enrique Ruiz, told me that they had started the year's grape harvest and would stomp on some of their most selective grapes, I immediately made my feet available for the task.

The following day I headed for his vineyard, La Real Fábrica de Hojalata outside the village of Júzcar (otherwise known for the Smurf movies). Finally, I was to try grape stomping and understand why some winemakers still choose to use this ancient method for their most valuable vintages.

First, we stomp …

José Manuel in the bodega. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Enrique and his oenologist José Manuel Cózar Cabañas are waiting for me outside the classical bodega. After a proper hosing down of my feet, I get to do a trial round in a smaller tub where the grapes only reach up to my ankles. «These are Tintilla grapes», states Enrique while I get used to the squishy feeling of having crushed fruit between my toes.

The grapes that were picked at the crack of dawn, are gathered in tubs, and pressed by foot so that the raw grape-must comes in contact with the natural wax that grows on the surface of the grape skin. This is how the fermentation process gets activated.

Grapes on the vine with natural wax on the skin. Photo © Karethe Linaae

«We give the grapes a hand with the process so that the wine ends up how we want it», says the Venezuelan oenologist who became smitten by wine while studying chemistry in Seville. The maturing process happens completely without additives. «We keep in the grape stems, so they are in contact with the liquid», he explains as I step out of the small tub.

Wine stomping in miniature. Photo © Jaime Barrera

But the work has only just started. The real stomping is about to begin – this time in a tub that one could almost drown in, which contains 750 kilos of grapes. First, my feet get another hose down, of course. Then, I climb up a small ladder and let myself gradually sink into the bubbling, orange-coloured grape mass which clearly already has been given a couple of stomping treatments. Since the mush reaches well up on my thighs, I can neither run nor dance around in the barrel like they do in Hollywood.

While I stumble around like a drunk (not having touched a drop), it occurs to me that the ancient Greeks had a good idea when they used a rope suspended above, so the stompers could keep their balance. But practice makes perfect, and gradually I get into a sort of Zen rhythm – pushing the foot gently down and then sliding the rest of the body forward. The time-tested process instantaneously raises my appreciation and respect for nature production and the love of wine, as it is completely unreal and ever so cool to be able to stagger about in what just might be La Fábrica de Hojalata's most exclusive future wine!

The point is to stay on one’s feet. Photo © Jaime Barrera

This time around, I am crushing the white grape variety Moscatel Morisco in what is the bodega’s pioneer experiment of making what in old Spanish was called vino brisado. In English, it is commonly called orange wine due to the colour, but this can easily be mistaken for a Vino de naranja which gets its taste and flavour by the addition of orange peel. Vino brisado has still not received an official wine classification, despite being the most authentic wine one can possibly produce with a thousand-year-old process.

Only a small fraction of the grapes that are grown on La Fábrica de Hojalata will go through the stepping process, but all their wines are organic nature wines and are pressed with a hand press. In total, they expect approx. 700 bottles of ‘my’ specially stomped, amber-coloured vintage and 2,000 bottles of foot-pressed red Tintilla. In comparison to commercial wine producers, La Fábrica is a tiny winery, only making some 9,000 bottles per year. And while industrial wines are set to age after just 3-4 days, raw wines, or nature wines as they are called, spend up to one month while they ferment at their very own leisurely pace. «Instead of filtering and purifying the liquid, we wait until all the solids fall to the bottom of the batch before we hand press it. This way the wine purifies itself» explains the oenologist.

Vino Brisado and pressed raw wine. Photo © Karethe Linaae

José Manuel explains that in industrial winemaking the grapes are rinsed, sorted and stems removed before the juice is pressed in a machine. Thereafter, the first correction will take place when they add sulphur and adjust the sugar- and acidity levels with chemicals. If the must doesn’t have the characteristics and consistency that the producers desire, they will add it. And to ensure that the final product is as ‘clean’ and clear as possible, they remove the naturally occurring yeast and nutrients, and therefore have to add yeast and nutrients in addition to more sulphates. Other chemicals might also be added to ensure that the wine won’t crystallize in the bottle. While this type of mass-produced wine can contain up to 250 ppm (parts per million) of added sulphites, organic wine has a maximum of 115 ppm and raw wine has under 50 ppm. A wine totally free of sulphates does not exist, as all wine has naturally occurring sulphites (under 10 ppm).

Safely out of my first ‘grape bath’, my education on raw wines continues. For health reasons, La Fábrica de Hojalata only uses non-toxic food-grade plastic tubs for the pressing, instead of the traditional wooden tubs. They also use the latest technology in measuring apparatuses. «Raw wine does not mean unclean wine. We make our wine with the least amount of interference, as the natural grape juice has all the wine needs – yeast, acidity, sugar, and nutrients», explains the eager oenologist.

Nature wine from La Fábrica de Hojalata. Photo © Karethe Linaae

More than 8,000 years of history

For the longest time, it was believed that the Romans (think Wine-god Bacchus), the Greeks (who stomped grapes accompanied by flute music) or the Egyptians (who also made wine from dates, pomegranate and figs) were the first to make wine, but we have to go even further back in history to find what we today consider the world’s oldest winemaking technology.

In 2015 a group of archaeologists discovered some clay urns during an excavation of a Neolithic settlement in East Georgia. The urns that were dated to approximately 6,000 BC, had traces of wine and were decorated with paintings of grapes and dancing men. These Qvevri urns are now part of UNESCO’s World Heritage List and are still used in winemaking in Georgia to this day – some 8,000 years later.

If one thinks about it, even Homo Sapiens from prehistoric times who by accident squashed some berries underfoot could have inadvertently started winemaking. Since it now is proven that the Neanderthals in Andalucía made sophisticated art more than 50,000 years ago, couldn’t they also have made yeasted grape juice? We might not be here when the discovery is made, but it wouldn’t surprise me in the least if there is still proof out there that winemaking is even older than we now believe.

Grape stomping anno 2023

First steps. Photo © La Fábrica de Hojalata

Pisado, or Pieage as it is called in French, has been the universal winemaking tradition for thousands of years, but wine producers gradually converted to mechanical pressing – the method that now is the most common for almost all wine producers. So, why in heaven's name do some winemakers still stomp on their grapes, and why has this tradition recently got a renaissance?

First and foremost, I would argue that the trend with boutique hotels, gourmet restaurants and luxury wine tours has increased the demand for exclusive wines. People are willing to pay almost anything for a unique product. Furthermore, the environmental- and sustainability trend has probably also inspired the new wave of grape stomping, not to mention the Slow Food movement. People – at least those who can afford to - want to distance themselves from mass production and get back to the original means and methods.

Why crush the grapes with one's feet?

Oenologist José Manuel explains the process. Photo © La Fábrica de Hojalata

The human foot is the perfect tool for the job. The pressure is light enough that the grape stones don't break, which can give the wine an unwanted bitterness. As most modern grape pressers crush the stones, some port wine producers still use pieage.

There are in fact also practical reasons for using one’s feet. The natural fermentation process that gets initiated can prevent damaging bacteria and mould, at the same time as the stomping circulates oxygen in the tub. The grape skins, stems and stones that come to the surface as one moves the must, contribute to the wine's final colour, taste, and natural aroma.

Traditionalists insist that pressing the grapes by foot allows for better control of the wine's taste profile and produces more complex and textured wines with a unique terroir signature. There are numerous festivals that now include wine stomping. It has become a tourist attraction in for instance Napa Valley and Brooklyn!

If one feels a certain reluctance to drink wine that has been touched by unknown feet, keep in mind that cooks use their hands and that these are often in contact with much more dangerous bacteria than our feet. Furthermore, almost no human bacteria can survive in a wine environment. The fermentation process reduces the oxygen levels, and combined with the natural sugar level that gets converted into alcohol and the grape's natural acidity, all contribute to removing unwanted bacteria and pathogenic organisms.

Wine as poetry

Vineyard owner Enrique Ruiz. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Our little group leaves the bodega and seats ourselves in La Fábrica de Hojalata's beautiful garden while the sun disappears behind the Serranía mountain range. Enrique opens a hand-pressed Moscatel Morisco from 2020 which has a deep amber colour. «When you make a million bottles, you cannot do it the natural way. It would be impossible. And one must admit that there are some excellent industrially made wines, as well”, he admits.

«What happens with raw wine, is that you get hooked», José Manuel interjects. «The more you learn, the more you want to learn. It is a fascinating world.”

Oenologist José Manuel Cózar Cabañas. Photo © Karethe Linaae

We make a cheer for this year's grape harvest, and I cannot resist but wonder if a great oenologist must be not only a good scientist but a bit of an artist.

«There are oenologists who are engineers who learn how wine should be made and follow this in every minute detail. And then there are other oenologists who are more like poets. They have the knowledge and the technique, but they make the wine with love – just like our guy here», says Enrique, referring to the oenologist at his side.

It is very doubtful that such an innovative winemaking method could have even been invented in our times. As the world gets increasingly antiseptic and mechanized, raw wine made by hand and foot, is really both old-fashioned and forward-thinking.

«A raw wine is a wine with a heart that you caress with your feet”, declares the oenologist-poet, and after the day’s stomping adventure, I have to say that I wholeheartedly agree!

The hard-working team outside the bodega after the first hand-pressing of the Moscatel Morisco. Photo © La Fábrica de Hojalata

2

Like

Published at 8:38 AM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 8:38 AM Comments (0)

UBRIQUE - The White Village that became the world’s leather capital

Thursday, September 21, 2023

Prototype of Dior's first suitcase that was made in Ubrique. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Where are Dior’s handbags, Prada’s fashion accessories and Cartier’s leather-covered jewellery boxes made? In a sweatshop on the outskirts of Paris? In a factory in China? Or perhaps in the fashion district in Milan? No, many of the leather goods of these and other exclusive brands are made in a remote rural Andalusian village by the name of Ubrique. Want to know more? Join me on a visit to get acquainted with the town's leather history and to separate the rumours from facts regarding Ubrique’s almost mythical leather industry.

Hidden, but not forgotten

Ubrique – tucked in a valley. Photo © Manolo Canto

There is no easy way to get to Ubrique. Whether you come from the coast or from the inland, you end up on a narrow corkscrew of a road that you must follow down to the bottom of a secluded valley where the village is located. It is not only hidden, but most of the companies who have leather production facilities in the town, work behind locked doors. The companies hired to make the latest leather accessories for some of the world’s most prestigious fashion designers and their designs, are highly confidential. In fact, it is so secret that the employees must sign a confidentiality agreement and are not permitted to bring their mobile phones into the workplace. For this reason, I decided to make my first stop at the town's leather museum where they gladly share information about Ubrique's leather history.

Leather museum in Ubrique. Photo © Manolo Canto

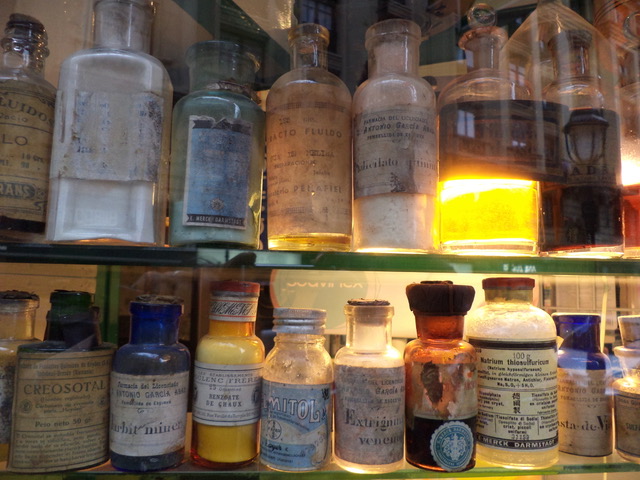

El Museo de la Piel is housed in a former Capuchin monastery on a slope above the town centre. The building has been newly restored and contains an incredible collection of leather articles, tools, photos, furniture, and equipment that show the development of the leather industry in this area in the 19. and 20. Century. The prime instigator of the museum is the passionate Maribel Lobato who started the collection (often from landfills and rubbish bins), gathering stories from the oldest inhabitants, and who still gives guided tours of the museum. Regretfully, she doesn’t speak English, but the museum is truly worth a visit even if one does not understand Spanish (Price 3 €). Should one want to get one's hands dirty, Paco Solano offers workshops for school classes and other interested parties who return home with a self-made leather purse from Ubrique (Course fee 5 € per person).

Paco Solano will teach school classes how to make their own leather purses. Photo © Karethe Linaae

These days, most of the leather articles are produced in larger plants located on the outskirts of town, but just a few decades back one could hear the hammering from the leather workshops that one could find on virtually every street and alley in town. All the inhabitants used to work in or for the leather industry, including children down to the age of six. And everyone had their own wooden leather hammer - called patacabra because they looked like the hind leg of a goat.

Collection of donated ‘patacabras’ at Ubrique’s leather museum. Photo © Karethe Linaae

It wasn’t an easy task to feed an entire family in rural Andalucía in the past. Therefore, the workers were given the opportunity to bring home extra work - after a 12-hour workday, seven and later six days a week. Every single piece of leather had a use - including leather from chicken legs that were boiled and pressed and used as watch straps, ox testicles that were made into tobacco purses, and fish skin that was made into shoes! As the fame of the town’s leather works grew, Ubrique started importing leather from all around the world.

Maribel Lobato tells the fascinating leather history. Here with a tobacco purse made from ox testicles. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The villagers were hard-working, persistent, and forward-thinking. They saw the need for souvenirs on the coast and made inexpensive leather articles decorated with Spanish bullfighters and flamenco dancers – articles that sold like hotcakes when the mass tourism started on the Costa del Sol. Ubrique was also the place where they started producing the official leather covers for the passports of almost every country in the world, including Spain, France, England, Italy, Portugal, Israel, Venezuela and Mexico. Not to forget the fashion accessories. In the museum, one can see the prototype of Dior’s very first leather suitcase made right here in Ubrique.

Leather covers for international passports were made here. Photo © Karethe Linaae

New life to the industry

Entrance to town. Photo © Manolo Canto

It is almost unbelievable that a tiny remote town off the beaten path in Andalucía is currently the world’s largest leather bag producer and exporter – especially since the leather they utilize does not come from the area, but from Italy and other countries. A couple of decades back, some of the workshops in Ubrique began to close their doors, because their large international clients moved their production to Asia to save money. There were rumours circulating that some designers had their bags fabricated in China to subsequently put a Made in Ubrique-label on the goods. Whether it is true or not, the trend didn’t last very long, as the designers soon discovered that the quality of the goods could never compare to the products made in the little Andalusian village. Hence, the clients came back to the town, which today hires more people and makes more leather bags than ever. According to the town statistics, they produce between 5,000 and 9,000 bags a week, which is more than any other place on the planet. Ubrique’s exclusive leather goods are sold to more than 50 countries (including France, the UK, Italy, China, the USA, and Japan) and produce accessories for some of the world's most renowned designers.

Ubrique’s leather history made in leather. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I am lucky to be invited to Adana Piel, one of the town's leather producers. The owner, Antonia González, took over the business from her father and has now opened a second production facility. While she describes her father as «a Gepetto» (Pinocchio’s father), she herself is more of a businesswoman. Her company produces several hundred exclusive leather bags every day, both by hand and with the aid of modern machinery. We rush past the diligent workers who come here to work from all over Spain and Latin America.

Factory owner Antonia González and designer Manolo Canto from Adana Piel. Photo © Karethe Linaae

In the workshop, I also meet the photographer and designer Manolo Canto who is currently creating Adana Piel’s own line of handbags, Briza. I am graciously allowed to take a few photos, though Antonia immediately points out that the bags are only prototypes and are not approved for production yet.

Prototype of Briza handbag designed by Manolo Canto for Adana Piel. Photo © Karethe Linaae

On the walls of their office, one can admire the company’s former designs which include handbags by Prada and, one of my favourites, Jacquemus. His collection of world-renowned mini handbags was recently produced in giant format, given wheels, and driven through the streets of Paris. But the actual bags were produced here in little Ubrique!

While most of Andalucía’s white villages suffer from depopulation and unemployment, Ubrique is constantly looking for skilled labourers and has trouble housing all the leather workshops. The town is alive and well, growing and prospering. And there is only one reason – the excellent and superior quality of their leather production.

From the Anana Piel leather workshop. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Make a trip to the village and experience the leather history of Ubrique for yourself. I can assure you that you will leave town with a new handbag or a new designer belt from one of the many leather stores on the town’s main street.

Window to Ubrique. Photo © Karethe Linaae

UBRIQUE DATA:

Inhabitants: 16 383

Inhabitants who work directly or indirectly with leather: 80 %

Number of leather factories and workshops: approx. 200

Types of products:

handbags, wallets, belts, suitcases, briefcases, mobile covers etc.

International brands who make/made leather handbags and accessories in Ubrique:

Dior, Louis Vuitton, Loewe, Carolina Herrera, Polène, Chloé, Gucci, Chanel, Jacquemus, Strathberry and many more.

Selection of classic Ubrique designer bags. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 5:01 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 5:01 PM Comments (0)

Here comes the gas man!

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Rafa, el bombonero. Photo © Karethe Linaae

If you believe you have a tough job, think again. One of the most demanding occupations here in Spain must be to deliver the gas bottles to the country’s homes and businesses. I had a chat with our local bombonero and discovered that he lifts close to 10,000 kg – per day!

In almost every Spanish neighbourhood you know when el Repartidor de Butano is on his way. First, you hear the honking or beating on metal when they announce their arrival, and then the rattling from the truck as el butanero or el bombonero as the locals here call them, drive around to deliver the easily recognizable orange gas bottles simultaneously as they pick up the empties that residents leave outside their front doors.

Just like people in other parts of Europe got coal and firewood delivered to their homes in the old days, most of the Spanish population still receive gas on their doors – unless they live in a modern complex where the gas is supplied directly via pipes into the building. For us Scandinavians who associate gas with BBQs, cottages, and camping, it is a bit surprising to realize that gas is still delivered by hand to Spanish households. The tradition started under Franco when a state-owned gas company had a monopoly. And even if the gas companies now have steep competition from other energy sources, los bomboneros are still an important part of the Spanish streetscape.

Deliveries in every street and alley. Photo © Karethe Linaae

45 % of the Spanish population – or more than 8 million households – still used gas for heating and cooking in 2020. The main reason is that gas is cheaper than electricity. Gas prices fluctuate amongst others due to transportation fees, crude oil prices and world events, and in the past decade, the price tag for a bombona has varied from ten to almost twenty euros. Some might have reservations about having something that explosive in our homes, but for people around here, that’s what people are used to.

The approximately 65 million gas bottles the Spaniards consume yearly are filled with liquid petroleum gas (LPG) or natural gas of either butane or propane. Most of the gas comes from the multinational Spanish company Repsol, which is the country’s biggest supplier with more than 2000 employees just delivering gas bottles all over Spain.

This not-very-enviable job is one that most of us simply couldn’t handle, if nothing else, due to the weight. So, who are these tough guys who pick up gas canisters like they were a litre of milk?

Rafael Dominguéz Naranjo. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Meet Rafa, el bombonero

Rafael Dominguéz Naranjo (48) is almost like an institution in the town of Ronda. Everybody knows him and expects his truck to come by every single tiny alley in each neighbourhood three times per week. I always look upon him with a mixture of awe and amazement when he picks up a gas bottle from the open truck, brings it straight up over the guard rail and onto his shoulder – hour after hour, day by day, in the frying Andalusian summer heat and howling winter storms. And if that isn't enough, Rafa is always smiling and friendly and even helps bring the monster inside the house should one need it. Despite the demands of the job, their salary is barely 10 euros per hour (June 2023), so a generous tip is not just good manners, but both well-deserved and should almost be obligatory!

One day I asked Rafa if I could interview him.

-Why on earth would you want to talk to me, he asked surprised, and based on his reaction I can guarantee that not a living soul have shown any kind of interest in his occupation before. I explained to him that his job is quite unique for many foreigners because in some countries (like my native Norway) people generally do not use gas in their homes. So, with a shy smile, he agrees that yes, he will share his story.

Rafa started as a bombonero when he was 19 years old, and besides a few months in construction, he has delivered gas bottles ever since – soon 30 years!

-In the winter I deliver between 180 and 200 bottles per day, but in the summer when we sell less, I only deliver 90-120.

-Only, I exclaim, and he shrugs his shoulders.

The full bottles weigh almost 28 kilos, which includes the metal canister plus 12.5 kg of liquid gas. I do a quick calculation and estimate that he carries between 2500 and 5000 kg every single workday. But that is not all, informs the humble worker. Every bottle is in fact lifted four times. First, when he loads the full tanks onto the open truck in the morning, next, when he delivers them to the homes, then when the empty tanks get picked up and finally when these must be loaded off the truck at the end of the day. At the same time, one must not forget the almost Rubik-cube-like system and the eternal game of musical chairs on the truck bed itself, as Rafa moves the full tanks towards the edge and the empties towards the centre of the truck.

Rafa on an ordinary day. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Then, there are the large industrial gas containers.

-The big tanks which weigh 62 kilos, are sold to restaurants and hotels where there is a need for stronger pressure to push the gas up several stories. I also put those on my shoulder, but my colleagues carry them together.

The job consists of fetching the gas cylinders at the local depot and delivering them to customers, whether they are businesses or private clients. Rafa almost always works alone. Together with two other bomboneros, the three of them deliver all the Repsol gas bottles in town in addition to supplying a handful of smaller villages in the vicinity. When they deliver to apartment buildings, they still must deliver straight to the client’s door. This means using the elevator when available. If there is none, or it is out of order, they must use the stairs. Rafa will usually take one tank on his shoulder and another one in his spare hand, and if he has more deliveries in one place, he uses a handcart.

-Our obligation is to deliver the gas tanks to the customer's door and not any further. But I always help the elderly customers and bring the bottles to where they store them. I even connect the bottles if they need me to. But not all bomboneros do that.

Rafa admits that it is impossible that the job does not affect one's back after so many years. When it comes to safety, the canisters lacked a safety valve in the past, so they exploded on occasion. But that doesn’t happen anymore, he assures me. Gas bottles in homes are much less common now than in the past, and every year there are more alternative energy sources. I ask Rafa if he believes his occupation will exist in 10 years' time.

- Yes, I believe so. There is gradually less work for us, but in the villages where it is more costly and difficult to lay gas pipes, I believe they still will need bottle deliveries.

Heavy lifting. Photo © Karethe Linaae

According to our almost tireless gas man, the toughest part of the job is when he arrives at an apartment building without an elevator or when it is impossible to find parking in the town centre and he must walk for blocks to deliver the bottles. And the best thing about his occupation is the contact with the customers.

- After all these years I practically know everyone in town, and people almost always take time for a chat. Most people are nice, but of course, there are all kinds...

Just as quickly as it started, our conversation is over. Rafa pops a gas bottle up the street and returns with an empty one. Then he hurries on to some 99 other deliveries before his workday is over.

Gas deliveries are one of those everyday occurrences that one sees here in Spain, but perhaps not often think about. It might be a dying trade as our society moves steadfastly towards full automation and complete digitalization. But in the meantime, we can still enjoy hearing the jolly honking announcing that the gas man is here!

99 deliveries left to go. Photo © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 5:27 PM Comments (2)

4

Like

Published at 5:27 PM Comments (2)

Summer sizzle

Friday, August 18, 2023

Sun over Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

We know it is summer in our Andalucian hometown when the only time it is liveable outside is before 9 am in the morning or after 9 pm at night. The hottest we experienced was the day we passed a thermometer outside a pharmacy, measuring 52 degrees. Not to forget that time during our first summer here when we were foolish enough to park right in the sun in August in Jerez de la Frontera and came back to 57 degrees inside the car. Not fun…

Summer fatigue. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Of course, one cannot completely avoid the southern Spanish summer heat, but my husband and I have learned to wake up at dawn, go to our allotment garden by seven and do our shopping as soon as the stores open or just before they close at night. Otherwise, we fight the heat with an endless selection of cold beverages, Spanish hand fans, SPF 50, face spritzers in every handbag, an eternal production of ice cube trays and experiments with cold soups, all windows and doors closed during the day, fully open doors (with mosquito net) and electric fan at night, cooled-off sheets (yes, you can put them in the fridge!) and an emergency sofa bed in the basement should it get particularly intolerable.

Walk at sunrise. Photo © Karethe Linaae

We know it is summer in Ronda when the fields are dusty gold, and no green straw of grass is in sight. When there hasn’t been raining for months and no prospect of precipitation either. When the town announces water restrictions (that they themselves never comply with) and even the neighbours stop washing their cars with a hose.

Workers searching shade. Photo © Karethe Linaae

We know it is summer when the neighbourhood kids who run around are tanned as nuts and spend most of their waking hours jumping in and out of any pool that comes their way, as here school don’t start until the second week of September. We often hear children’s chatter and laughter long after we have gone to bed. When the toddlers finally get herded inside by their parents, we lay listening to the clicking sound of the geckoes that climb on the exterior walls hunting for mosquitos and other bugs, and as far as I am concerned, they can have the whole lot!

Antón cooling off. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The summer is also the wedding season in Spain. I cannot imagine how the women in the bridal party can stand getting into the rather tight and often synthetic dresses, monumental feather hats and towering stiletto heels to teeter up the cobbled road to the Espiritu Santo church in the height of summer - but what doesn’t one do for love!

Summer also means village fiestas with ceaseless Reggaeton music and piped and live flamenco into the wee hours.

Night movie. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Most Scandinavians choose to travel north in this part of the year, and who can blame them? I have always had big plans of finding a holiday substitution post on a weather-exposed lighthouse north of the Arctic Circle every August. Oh well, perhaps another year ...

Reflection. Photo © Karethe Linaae

2

Like

Published at 5:21 PM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 5:21 PM Comments (0)

Worlds of the wise

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Ceramic art, Übeda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

As you read this, my husband and I are travelling around Morocco by rail to mark my 60th birthday. I am NOT sharing this news to attract felicitations (Please don’t!) or sympathy. Rather the contrary. I usually keep very quiet about such occasions and am no great celebrator of birthdays in general. I cannot remember the last time I had a party with friends and cakes and candles and all that jazz. On the other hand, I do recall a whole lot of birthday trips, excursions and adventures which will live in my memory for as long as I am blessed to have some.

Museum, Sevilla. Photo © Karethe Linaae

As my Catalan friend Juncal says «If anyone ought to be congratulated on my birthday, it is my mother. After all, she was the one who brought me to this world!» However, since I now sitting here wondering how I got to this point - and so very quickly – I have decided to share some reflections about life in general.

First, the hard facts. Ageing is something we all share. From the day we are born, we age – every day, hour, minute and second. To live is therefore to age. It is nothing we can avoid and certainly nothing we should be ashamed of. Yet I believe that most women my age are reluctant to or outright refuse to admit how old they are.

Blurred lines. Photo © Karethe Linaae

I am rather the opposite. I usually lie upward and have been saying “We who are in our 60s…” for a while now. Perhaps because I think it is funny and quite absurd. The (good) voice in my head is still the same as 30 years ago, and like my son pointed out last time we met, I still act like a fourteen-year-old most of the time.

Other-wise. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Lately, I have become acutely aware of some age-related Spanish expressions, like código de barras (Bar Code) which refers to the vertical lines that appear with age on one’s upper lip. Not to mention alas de murciélago (bat wings) which naturally refers to the loose flesh and ‘love muscles’ that hang on the underside of one's upper arms. Yes, indeed, age creeps upon us, but thankfully it also usually brings a tad of wisdom. And the great thing about getting older is that one cares less and less about what others think. Like my late mother-in-law used to say on that very subject: «No me dan de comer» (They don’t feed me).

Potions. Photo © Karethe Linaae

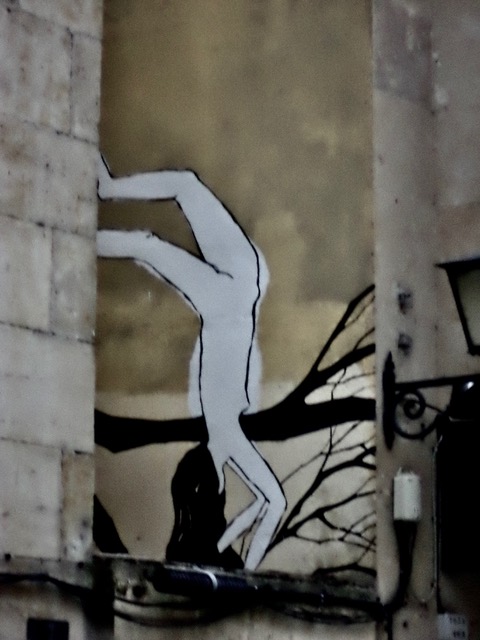

With my somewhat advanced years in mind, the only things that really matter to me are keeping my health and my head intact. If I still can knot myself into a human Pretzel and stand on my head in my morning yoga, who cares about a few wrinkles? Every scar and crevice is duly earned. My goal for the, let's say, next 20 years (not to be too greedy) is to see more, breathe more profoundly and always to stop and smell the jasmine and orange blossoms.

Yogini street art. Photo © Karethe Linaae

A sermon by a Norwegian priest really resounded in my heathen heart. It spoke about how we always live ahead of ourselves. I am certainly guilty of thinking about undone tasks while I eat and making mental lists of what to do the next day if I wake up in the night. The only time that I possibly live more ‘in the now’ is when I have my hands deep down in the dirt in our allotment garden. So perhaps I should add digging in the soil as a thing I should do more of in the next couple of decades.

Step inside. Photo © Karethe Linaae

The other day I came upon an interview with a woman who became 122 years and 164 days old (not that I expect to get there!). She has now passed on to greener fields, but in her lifetime, she was a real inspiration. She took up a new hobby – fencing- when she was 85, biked until she was hundred, and quit smoking (a habit she started at 21, in 1896!) when she was 117 because she was too blind to light her own cigarettes. In a conversation with a journalist on her 120th birthday she said;

“To be young is an attitude. It doesn't depend on your body. In fact, I am still a young girl. I just haven’t looked that young for the past 70 years.»

Graffiti. Photo © Karethe Linaae

So, cheers for Jeanne Luise Calment. Remember to add life to your years, whether you celebrate it by blowing out candles, or skip the cake entirely and go straight for the adventure.

Diving in. Photo © Karethe Linaae

4

Like

Published at 6:08 PM Comments (1)

4

Like

Published at 6:08 PM Comments (1)

How Spanish have we become?

Thursday, May 4, 2023

Spanish eyes... Photo © Karethe Linaae

After living in Spain for a decade, it is almost unavoidable that we have begun to inherit some Spanish habits, attitudes, and even ways of being. It isn't as if we suddenly start dancing Flamenco in the streets and speaking while everybody else is talking. The changes are more subtle than that, as we, of course, remain English, Chinese, or Ukrainian (or for us, Mexican and Norwegian) at heart. Some things never change, yet most of us must admit that we gradually have become just a tiny bit more ‘Spanish’.

Flamenco. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Law-abiding citizens

On some occasions, I realize that Andalucía has crept under my skin, and at no point is this more evident than when I come home to my native Norway. It starts already at the airport since I am no longer accustomed to being surrounded by tall, naturally blonde, and naturally white-haired individuals who gladly line up a long time before the gate opens. But then again, we do reside in a town with only half a dozen Scandinavians.

New face. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Everything in Norway seems new and different to me the first couple of days, like the cool and fresh air as one steps out of the plane and onto Norwegian soil, that more than half the passengers stop to buy Tax-free upon arrival, that there are no fights at the luggage carousel, the heartfelt, but restrained hugs at the exit, no illegally parked cars or honking, even if there are no police around, that drives use their turn signals in roundabouts and generally follow the traffic rules, that cafes leave the chairs and tables outside - without chains – when they are closed, and flower stores let people serve themselves and pay by VIPS when they are closed and that there are hardly any garbage around.

The sound level

Ronda. Photo © Karethe Linaae

One particularly noticeable difference between Spain and Norway is the sound level, and it is something that is almost impossible not to feel in one's bones.

Take a railway compartment. In Norway, there will of course be muted conversations between travel companions, but otherwise, no grand gestures and loud banters across the aisles. Spanish buses and trains, on the other hand, sound like a cackling henhouse with unrestrained laughter and energetic exchanges. If they didn’t know each other before, they will get to know each other during the journey. The volume is regulated by how loud others are talking. If one waits until all are quiet and it is one’s turn to talk, one will end up waiting forever. So, the only way is to pump up the volume.

Pump up the volume. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Of course, one mustn’t utter a sound when entering a quiet zone on a Norwegian train. I did the mistake of greeting the passengers with a polite ‘hello’ when I came into the compartment (at least I managed to stop myself from blurting out a cheery HOLA!), but nobody even raised their heads. In Spain, we often see Silencio signs in waiting rooms, hospital corridors and other sound-sensitive areas, but I have certainly never noticed any difference in the sound level.

The temperature

Norwegian in the south. Photo © Karethe Linaae

And then it is the issue of the cold. I have lived outside of Norway most of my life. The northernmost point I have resided in the past 25 years, was Vancouver, BC, which is at the level of Nice. Though there might not be a scientific explanation for this, I believe that one gradually develops ‘thinner skin’ by living further south. At least for myself, I have become a real wimp when it comes to cold temperatures. While my sister in Norway who never wanted to even get her head wet as a child now has become a regular ice-bather up north, I take pleasure in being a true Andaluza and wearing long pants and a jacket when the tourists start to flood the streets in shorts and flip flops in early February.

Andalusian party garbs. Photo © Karethe Linaae

After years in Spain, I have also thinned out my winter wardrobe. One rarely needs a full-length duvet coat and polar mitts in Andalucía. We use ski underwear a couple of times during the winter, but that is only because we live 800 meters above sea level. Otherwise, I have gotten used to the heat outside, and the cold inside, as Spanish homes tend to be freezing. I have never been so cold inside as in houses in Southern Spain. And in contrast to Norway, where people overheat their homes and have all their ambient lamps on for cosiness-effect despite astronomical electricity prices, we go outside to heat up here down in the deep south.

The social side

Amigos. Photo © Karethe Linaae

When one lives in a traditional Andalusian town and is constantly surrounded by Spaniards, it will affect one's way of communicating. Gradually and perhaps without being aware, our arms will lift and start to move more as we speak. Throughout the years, our volume will also increase a tad, though I believe we always will keep our measured personal comfort zone.

Keeping personal distance. Photo © Karethe Linaae

In Spain, we get used to talking with neighbours and other customers when we stand in the line-up at the Butcher’s or while the Green Grocers tally up our purchases. We say «Jesus» when someone sneezes on the street, whether we know them or not, and we always wish «Buenos Días» to the people we encounter on a nature trail. But from the reactions I have received, these are not the general custom in Norway.

Market. Photo © Karethe Linaae

During my last trip back ‘home’, a young Spanish woman came rushing up to the gate announcing on her mobile that she arrived just in time and looked forward to starting her new job. Usually, being a true Norwegian, I would just have thrown a discrete glance at her and not said a word. After all, one doesn’t talk to complete strangers! But this is when my inner Española takes over, so I asked her if she was a nurse. (There are many Spanish healthcare workers working abroad). Irene from Sevilla, as she introduced herself, explained with a big smile that she was a pastry chef and was starting her new job in Oslo the following day. It turned out that she had never flown before, did not know how to board a plane and did not have a passport. Had it not been because I am now a little bit Spanish, I would probably have been standing there staring blankly at the departure boards, like everyone else instead of offering to help her. Not because we Norwegians are particularly unfriendly, but because we as Nordic beings ought to and want to manage everything on our own.

The helpfulness

Soccer fans. Photo © Karethe Linaae

My so-called ‘Spanish-ness’ is not always well received. During a visit to Norway last summer, my husband and I set off on a forest walk we had heard about. I was not sure which street we had to take to get to where the trail began, something I thought would not be a problem. I knew the language of the natives and could always ask for directions. After all, it was broad daylight. Soon enough we passed a man who stood polishing his already shining Volvo. «Hiii. Could you tell us where the trail to the Hjertnes-forest starts», I asked. The man startled, peered up at us as if we had come to rob him and mumbled something about «up and over there». Then he went back to his polishing cloth without another word. His behaviour surprised me. Where had he spent his sheltered life to be so uncomfortable by two semi-old folks asking for directions to a simple nature trail?

Gonzales, a genuine Spaniard. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Had this been Andalucía, the man would have come over to us (the car polisher kept a safe distance so he could rush into his house, bolt the door behind him and call the police if we entered his pristine driveway). An Andalusian would have given us a long and friendly explanation and if we had not understood the directions, he would point us in the right direction or follow us up the street. Come to think of it, he would likely have offered to join us on the walk to make sure we wouldn't get lost.

Andalusian. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Despite the lack of directions, we found the trail and had a lovely morning, though absolutely everybody we met, including children with their parents, looked suspiciously at us when we greeted them and wished them a pleasant day.

So perhaps one should be grateful that one has become a tiny bit Spanish, after all…

Passion. Photo © Karethe Linaae

5

Like

Published at 7:13 PM Comments (4)

5

Like

Published at 7:13 PM Comments (4)

Our decade in Andalucía

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

Ronda. Illustration by Virgínia Jiménez Perez

Unbelievable, but true! Exactly ten years ago to the day, on a stormy night on November 3rd, 2012, my husband and I arrived in the small town of Ronda in Andalucía with a couple of suitcases. Our few other earthly possessions that we hadn't given away, donated, sold, recycled, or thrown away, sat in a container on a dock in Canada to be dealt with at a future date. We had spent a single night in the town before, and now we were suddenly here indefinitely. The plan was to stay in Ronda for a few months before we travelled to other towns in search of our slice of Andalusian paradise. But gradually we understood that we had more or less found our paradise right here!

Casita 26. Illustration by Virgínia Jiménez Perez

What happened during the last ten years? How did we handle the transformation from living in a cosmopolitan city of millions to becoming adopted Andalusian village dwellers? Without pontificating too much, here is our last decade made in bullet form:

- We became intimately acquainted with Spanish bureaucracy when we searched for, found, purchased, and renovated a ruin after an archaeological excavation and a two-year wait for our building permit.

- I had to learn TWO new languages – Spanish and Andalu’ and subsequently forgot most of my French.

- We had to take our Spanish driving licence from scratch - classes and all - though we had driven for over 70 years combined. The first Spanish book that I read cover to cover was the 318-pages driving manual with the intricate Spanish traffic regulations.

- We became the proud renters of a community garden plot and immediately realized that we knew nada about gardening in the Spanish south.

- My 21. Century transatlantic immigration tale was published as a book in the USA.

- We became political activists, me as the co-founder of Ronda’s first official volunteer environmental clean-up group and later as vice president for the public trail association while my husband became a health specialist for local TV and lecturer for the town's cancer association.

- The neighbourhood kids came to get help with their English homework, and then came their teachers …

- We became active members of the hiking association Pasos Largos and confirmed that the old Andalusians are tough as nails!

- I began to write freelance for five magazines and became the editor of one of them.

- We survived seven weeks closed in our tiny little home and two years of wearing masks during Covid-19.

- With much help from friends and acquaintances, my book (Casita 26) was translated into Spanish and will be released by a wonderful Spanish publisher at the same time as the second English edition. It is supposed to happen muy pronto (very soon).

- A genuine rondeña gave me a flamenco dress, but to her great disappointment, I never learned how to dance La Sevillana …

Andalu' leg. Illustration by Virgínia Jiménez Perez

Our decade in Andalucía has been filled with joys and challenges. I still cannot stop pinching my arm to assure myself that it is true – that this mind-boggling place truly is our home! It is a privilege I hope I will never take for granted.

Your slice of paradise might be somewhere entirely different, but for those who have found your dream home and for those of you who might still be looking – enjoy the process and treasure every minute of the journey.

And as for the next decade - my only plan is to finally try to find the time to write that sequel to my book so you will know what happened to our Ronda ruin and our tailless lizard.

Our house pet, the tailless lizard. Illustration by Virgínia Jiménez Perez

5

Like

Published at 9:51 PM Comments (3)

5

Like

Published at 9:51 PM Comments (3)

7 stops from Rome to Tokyo - Life of a SAS air hostess in the 1950s

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

One of the many times that I have flown across the Atlantic, they showed a video of Air Canada’s 75+ years of history. I decided that I would ask my mother, Aase Linaae, about her experiences as an air hostess in the 1950s - a time when jet planes, charter trips and mass tourism still didn’t exist.

The front page of the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten, February 1957. Aase (right) together with the Swedish captain and air hostess from the first commercial flight over the North Pole.

Aase was born in a rather conservative Norwegian town in 1930. She grew up at a time when women, or at least married women, weren’t meant to work outside the home. After completing a secretary school at a local business institute, Aase worked a year in an office in London, which was quite unusual for a girl from her town. But her desire to see the world was not satisfied. She subsequently spent a year as an au pair in France, where she met another young woman who had tried to become an air hostess for SAS. Although Aase was warned about the demanding multilingual interview, she decided to apply.

Air hostess training with diaper changes and basic flight mechanics

Emergency exit practice a la Houdini, Stockholm 1954. Photo © Aase Linaae

SAS, or Scandinavian Airlines Systems, a conglomerate of government-owned Swedish, Danish and Norwegian airlines, began their operations after the Second World War. When Aase applied to SAS in 1954, they had only had air hostesses for eight years. Before that, the position didn’t exist. At the beginning of Aase’s career, the names of all the Norwegian air hostesses could fit onto a single sheet of paper. Otherwise, the flight crew consisted of a captain, a first officer, a mechanic, as well as a navigator on longer hauls to for example the Middle East or the USA. The cabin crew consisted of a purser and a steward – these were also male and quite often gay, though such things were never spoken about out loud.

To fly, at least commercially, was still new and only very wealthy people and celebrities could allow themselves such a lavish luxury. The job as an air hostess was therefore the most glamourous job a young woman could wish for, other than being a movie star. It was basically every girl’s dream.

The Chef explains, air hostess course Stockholm 1954. Photo © Aase Linaae

More than 500 hopeful young women applied to SAS at the same time as Aase. All were between 23 and 28 years of age (otherwise you were considered “too old”). All had to be under a certain height (168 cm, in Aase’s recollection), and all had to weigh under 58 kilos. The applicants could also not wear glasses. Such were the prerequisites at the time, and it was all completely legal!

SAS air hostess course 1954. Photo © Aase Linaae

It was customary and practically expected that the air hostesses stopped working when they got married and had children. It wasn’t exactly a requirement, but just what happened. Air hostesses between the age of 30-35 were only given work in the summer when there was more air traffic. In the winter they were often put on leave or helped to retrain as ground personnel. If you had been flying for seven years in 1960 and were over 30 years old, the airline gave you severance pay. It was basically the airline's way to get the ‘ancient’ air hostesses to stop flying and end their careers when they became 30.

Fire extinguisher practice during air hostess training in Stockholm. Note the practical wardrobe… Photo © Aase Linaae

50 young women were called into the exam in Oslo to fill a handful of vacant positions on offer. Even with fluent English and French, Aase was terribly nervous and crammed German grammar until the last moment. “Ich bin nimmer in Deutschland gewesen” (I have never been to Germany). In her eyes, the other applicants looked much more appropriate for the role than her, but to her great surprise, she passed. Together with eleven other young women, Aase went on to a 2-month air hostess training course in Stockholm. Included in the curriculum were basic mechanics, meteorology, flight history, diaper changing and how to inject a syringe. However, they learned little to prepare them for what was to come…

Graduated SAS air hostesses, Stock holm 1954. Photo © Aase Linaae

Propeller flights, eternal turbulence and stilettoes

Just imagine working in one of those old propeller planes that could fly into the clouds, but never above them. Obviously, there was almost constant turbulence, combined with occasional gale-force winds from the North Sea. Add frequent stopovers to refuel on far too small and unwieldy airports. Throw in 30 Danish businessmen smoking cigars from take-off to landing. Put on some stiletto heels and a tight-fitting uniform and start serving three heavy trays at a time with an ample supply of genuine crystal glasses, silverware and piping hot dishes, directly from the oven. And that was only the beginning before the barf bags started to be filled …

If the air hostess needed to sit down for a few seconds, and the aeroplane was full, she would have to sneak into the cockpit with the pilots, where there was a folding seat. However, there was never time to sit down, as she was the only air hostess on board and every single passenger had to be told individually - in their preferred language - about the plane’s safety rules - because the speakers on the plane were only to be used for important announcements!

Boarding the old way. Photo © Aase Linaae

There were of course no unions for air hostesses in those days. While the cockpit crew was well paid, air hostesses earned less than the secretaries at the time. The roller trolleys that the female crew members recommended to their superiors, again and again, were only introduced as standard equipment about a decade later.

The air hostesses spent the first year flying within Scandinavia, which meant eternal fjordland turbulence with puffing Danes, arrogant Swedes, and neurotic Norwegians. From the second year with the crew, once the air hostesses had proven themselves ‘flight-worthy’, they were allowed to assist on longer flights. A flight between Oslo and Rome took the entire day and included three long stopovers in Copenhagen, Frankfurt, and Zurich. Very few people had been travelling outside their own country, not to mention to exotic destinations. Therefore, if you were lucky to work on a flight that was going to America, Africa, or the Middle East, you would have plenty of time to look around, as the return flight wouldn’t happen for several days.

Exotic destinations and long stopovers

Flying over Cairo. Photo © Aase Linaae

Take a flight destined for New York. After taking off in Copenhagen, there would be an overnight stopover with a change of crew at the airport in Prestwick in Scotland. From there, they had a nine-hour haul to Gander Airport in Newfoundland, with a stopover and refuelling again before continuing another five hours to New York. There, the plane would fly back with a new crew, while the original crew had three days in the Big Apple before their return.

Stopover Alaska. Photo © Aase Linaae

When Aase flew to Kenya – with five stopovers and a change of aeroplane during an overnight stay in Athens – there were only flights once a week. Hence, the crew would spend seven whole days at Equator Inn in Nairobi, including per diem, paid by SAS.

Hotel where they stayed in Tokyo

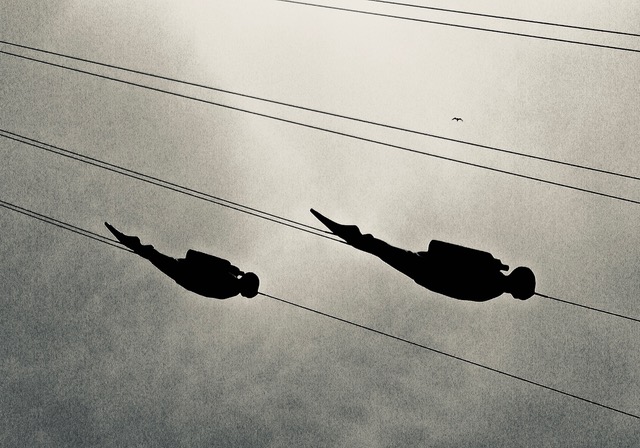

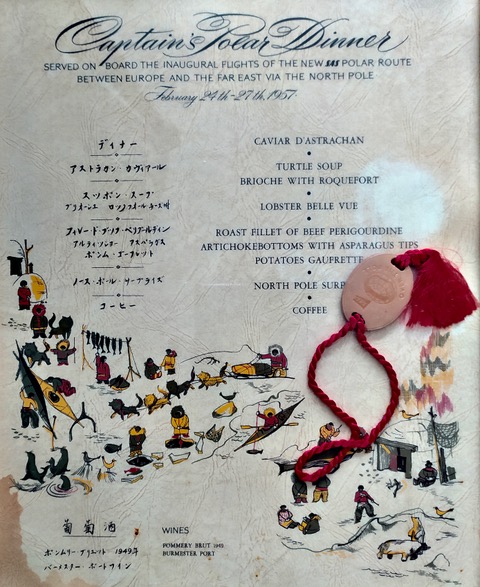

Although flights over the Polar region are common today, airlines had to fly long detours to avoid the Poles before SAS created the pioneer flight route across the North Pole. In the early 1950s, Einar Sverre Pedersen (1919–2008), a former navigator from WW2, educated in little Norway in Canada, developed a Polar Path Gyro-system for SAS. This navigation system was to bring the flights safely across the Arctic Ocean. Aase was part of the crew on the inaugural flight in 1957. It was the first-ever commercial flight with a DC7 over the North Pole, which established a new SAS route between Europe and what they then considered the very Far East. As the plane passed the North Pole for the first time, they crossed paths with another SAS flight that had started from Japan. The world had suddenly gotten a bit smaller.

Souvenir ashtray from first commercial flight over the North Pole. Photo © Karethe Linaae

Menu for the inaugural flight over the North Pole

Flying into the Eastern Block was always a problem for the pilots, as they were only allowed to follow a narrow specially designated air corridor when they flew across communist countries. Nothing would allow the pilots to deviate from the corridor, and if they did, they would risk being shot down. The weather reports from these countries were also far from adequate. For this reason, it was only natural that they flew into a massive storm one day they were heading for Istanbul.

Istanbul Mid-1950s. Photo © Aase Linaae

Aase recalls that the lights went off in the cabin and both passengers and crew were shaken in the aircraft, while giant hail which sounded like machinegun shots, hit the fuselage from all sides. Everybody on board feared it was their last flight, including the pilots. After somehow landing in Istanbul, the fuselage was riddled with bumps and had to be completely overhauled. One of the pilots later told Aase that if one of the hailstones, which were large as eggs, had hit the engine, the result would have been catastrophic.

In the air anno 1950s. Photo © Aase Linaae

Aase flew for six incredible years. This was much longer than the average length of an air hostess career at the time, which was barely two years. She flew all the SAS routes and to all continents in the world, except Australia as SAS didn’t have flights there yet. During her last year on the job, Aase was stationed in a SAS flat in Rome and only flew to the Far East.

Aase in Tokyo with the Japanese SAS ground hostess during her last flight in April 1960. Photo © Aase Linaae

Her last flight as an air hostess in April 1960, took her from Asia and back to Europe. As usual, there were a few stops on the way:

Tokyo – Manila

Manila – Bangkok (overnight stopover with a change of crew)

Bangkok – Calcutta

Calcutta – Karachi (overnight stopover with a change of crew)

Karachi – Teheran

Teheran – Athens

And finally, Athens – Rome

Aase retired from SAS on the 1. of May 1960. She got married to my father 20 days later, but that is a story for another day…

When in Rome... Photo © Aase Linaae

3

Like

Published at 10:43 AM Comments (1)

3

Like

Published at 10:43 AM Comments (1)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|